Miners' strike: Voices from the Welsh coalfields

- Published

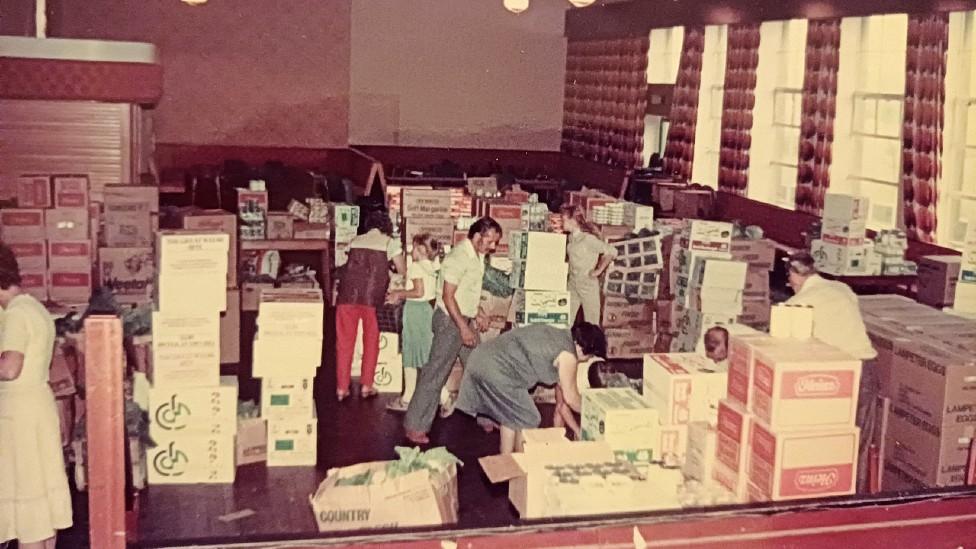

Food ready for distribution at Onllwyn welfare hall

The year-long miners' strike from March 1984 to 1985 changed the face of Welsh industry and many of its closest-knit working communities.

Wales' largest employment sector was in a desperate battle to save itself from being wiped out.

Three people whose lives were bound up with the action share their stories of the year the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the UK government under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher went to war.

Kim Howells, NUM research officer, later Labour MP for Pontypridd 1989-2010

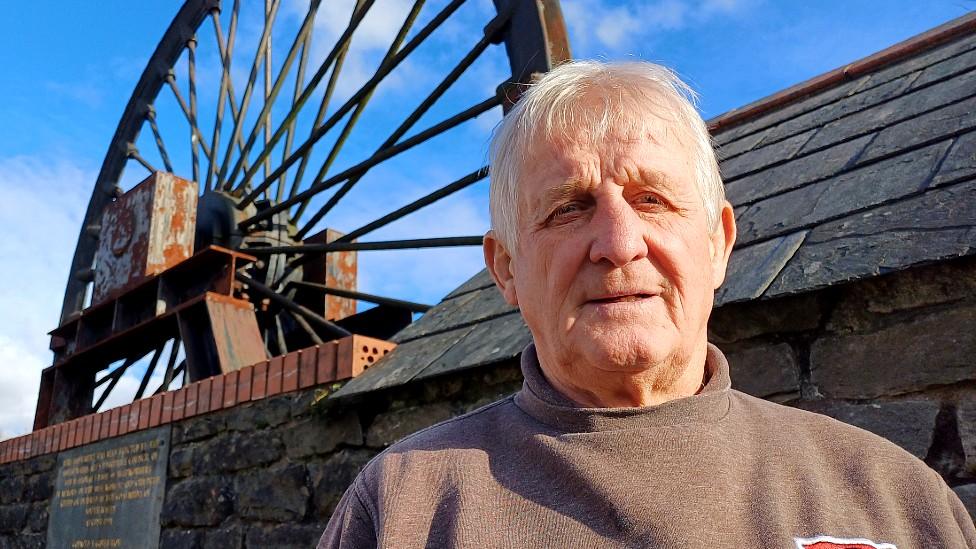

Dr Kim Howells, pictured at Rhondda Heritage Park, became an MP in the years after the strike ended

Kim Howells calls 1984 to 1985 "the most intense year I've ever lived through. Anyone who was deeply involved in it will always be scarred by it."

As a union officer, he was very aware of recent history in the 1970s, when the NUM had led victorious strikes and brought the country to a standstill at times.

But there was a vital difference. Then there had been widespread union support for strike action.

This time, less than half the membership had voted in favour, and with closures and job losses previously happening in the British steel industry, it also raised questions over how much coal would be needed.

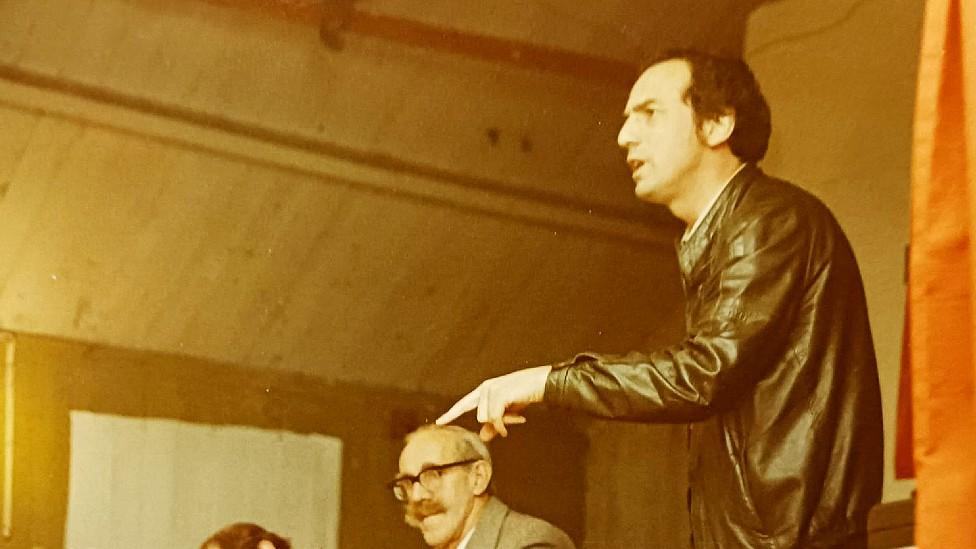

Kim Howells addressing a strike meeting

"That was a big problem for us because we began to realise that we were losing our markets everywhere," Kim said.

"A lot of the pits in south Wales were producing good quality coking coal that went to the steel industry in the foundries and those steelworks and foundries were closing all over Britain."

Although miners had voted nationally against strike action, Kim and others held a meeting and decided to picket every mine in south Wales.

"The majority of pits stopped work, [as men] wouldn't cross the picket line, even though there were only two [pickets] there," he said. South Wales became and remained the most solid area of the strike.

As the months wore on and hardship deepened, he recalls the community spirit that pulled people together to get through.

"It was a summer when lots and lots of people, including me, learnt how to grow vegetables. There were rallies constantly. People were marching in the streets. There were lots and lots of things organised for the kids of miners' families."

He said the whole community, not just those affected by mining, pulled together "in so many ways".

"I can only describe it as a kind of discovery of love for each other," he said. "It was an amazing period - a realisation that we all depend on each other and we all helped each other."

Ron Stoate, Penallta colliery NUM lodge vice chair

Penallta miner Ron Stoate: "You've got to stand up for what you think is right"

Ron Stoate was a 34-year-old miner in the Rhymney valley colliery of Penallta, Caerphilly county, when the strike broke out.

He called it the biggest learning curve of his life, and it forever changed how he saw institutions such as the judiciary and the police, leaving him "bitter and twisted", he said.

"I had a wife and two children to look after. I used to go to Nantgarw cutting to get a car full of waste coke for fuel, which we shared with everyone back home," he said.

As part of the picket action, "me and my brothers were arrested 10 times, me four times, them three each".

Ron described road blocks being set up by the police to try to prevent pickets from reaching mines, as well as what he saw as biased actions by officers.

"You had the police who were actively going, and I can say this from experience because it happened to a man in our pit, actively going to people's houses to ask them 'do they want to go to work?'.

"So they weren't just policing the strike, they were actively trying to break the strike."

Ron was at Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire, in June 1984, where almost 100 miners were detained.

Thousands of police and striking miners clashed violently in one of the darkest days of the strike, with the police accused of using excessive force.

Clashing police and miners at Orgreave

"The police took us there [in an escort]. Bear in mind that before that, the police were stopping us from going to places, and turning us back.

"You don't have to be Sherlock Holmes to work out what happened there. They took you there to deliberately do what they done. And when I go there, you could see ranks and ranks of police with short shields and long shields.

"And then to your left, police with dogs on long leads and to your right police on horses, and we was there in a t-shirt and a pair of jeans."

Despite everything, Ron says he has "no regrets at all", adding: "I wouldn't want to do it again, but I would.

"You've got to stand up for what you think is right haven't you?"

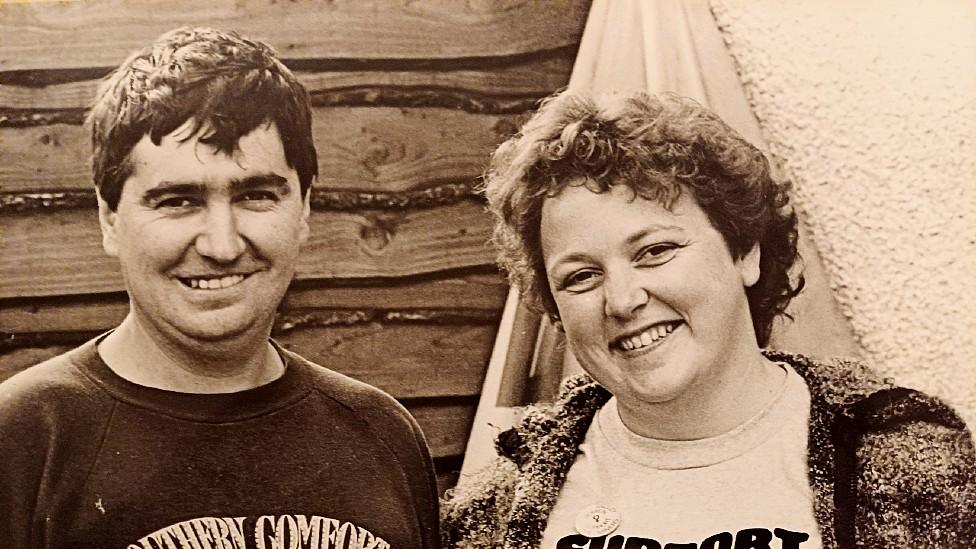

Christine Powell, treasurer of miners' support group

Christine Powell acted as treasurer to the wider district support group

Christine Powell, from Seven Sisters, Neath Port Talbot, was on her way to her teaching job in March 1984 when she drove past Blaenant colliery, where her husband Stuart was expecting to start his afternoon shift later that day.

It looked different to normal.

She said: "There were two cars in the park and a few chaps by the door of the pithead baths. So as soon as I got into work, I rang him and said 'you may as well stay in bed, as you've been picketed out'. Didn't have a clue that it would be 51 weeks later that he would go back to work."

She quickly got involved in helping form a support group locally, which joined forces with others nearby to become the Neath, Dulais and Swansea Valleys District Miners' Support Group.

Acting as treasurer, she spent a large part of meetings receiving donations of money, which initially went into a bank account.

But as the summer wore on, the government was seeking to sequester funds from mining groups. She and Hywel Francis, the historian and political activist who later became Aberavon MP, raced to the bank to remove £5,000 before it could be frozen.

"Over the next few weeks we tried not to use cheques etc. I accumulated £35,000 under the spare bed with my dog sleeping on the bed for security."

Christine's husband Stuart Powell worked at Blaenant colliery in Crynant when the strike began

She tried not to worry about having that amount of cash in the house on the basis "if you got past Butch, you deserved to have the money".

She also helped with food parcel distribution. Speaking from Onllwyn welfare hall, she remembers the work that went into feeding families who often had no income by this time.

"We knew roughly on a Sunday night how much food we'd need to put out that week. Kay [Bowen] would order it. And it all came here. This was the hub of the operation. Then, on Wednesday morning, some of the food parcels would be made up, and in others we transported the food required to the nine sub centres we had.

A Mini Metro filled with loaves of bread for distribution

"Basically any vehicle would do. There is a picture over there of how many loaves of bread and pints of milk you can get into a Mini Metro."

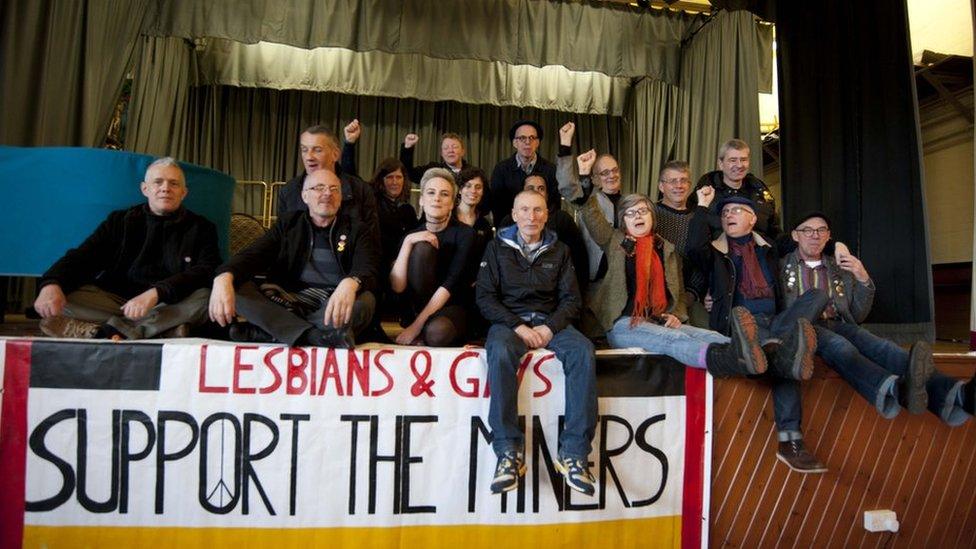

Onllwyn was also the place where a historic meeting between two seemingly very different groups of people first occurred: the local miners and members of the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) group, which travelled down from London to offer financial and practical support to the striking men and their families.

This story was told in the award-winning film Pride, which documented the links forged between the two and saw those mining families repay the gay community with support during the HIV and Aids crisis of the 1980s and 1990s.

Pride the film used some of the real-life miners and activists as extras

"They were major contributors, major contributors," Christine said.

"I remember in a short period of time £15,000 coming in. That's how we were able to purchase the van. But it kept coming in afterwards."

She was a protester at the Conservative Party conference held in Porthcawl, south Wales, when Margaret Thatcher was famously egged by a protester outside.

She said: "I can feel it happening now, the knot that starts in my stomach starts to rise and the anger is still there. Because when you're fighting hard for something and people who should be supporting you are undermining you, it's very hard to deal with that, very hard."

She thinks, overall "society lost", with the defeat of the miners and the disintegration of communities.

"Personally, as me as Christine Powell I learned a lot... and I think a lot of us did. So if you want to look at it from that respect, no we didn't lose.

"We didn't save the coal industry. But as individuals, we all grew."

MICHAEL SHEEN'S DIRECTORIAL DEBUT: An ordinary family caught up in extraordinary events

MEN UP: Five ordinary Welshmen embark on a surprising medical trial

Related topics

- Published18 February 2024

- Published4 January 2020

- Published1 October 2022

- Published29 January 2023

- Published13 March 2014

- Published10 October 2016

- Published11 February 2024