Keir Hardie: Wales' 'first World War One objector'

- Published

A documentary on Keir Hardie and south Wales' conscientious objectors is being premiered on Wednesday

While thousands were fighting for their country in World War One, hundreds in south Wales were fighting a struggle of their own as conscription threatened to force them to join a cause they did not believe in.

In 1917, communities were split over whether locals should support the conflict.

Seven men who refused to take part died in jail, while Labour's first Welsh MP Keir Hardie was said to have been left a "a broken man" after he failed to stop the conflict.

Now, new documentaries tell the story of anti-war campaigners and the lengths some went to to avoid service.

The project by the Made in Tredegar film company took researchers to places such as the Gwent Archives, Ebbw Vale and Cyfarthfa Castle museum, Merthyr Tydfil.

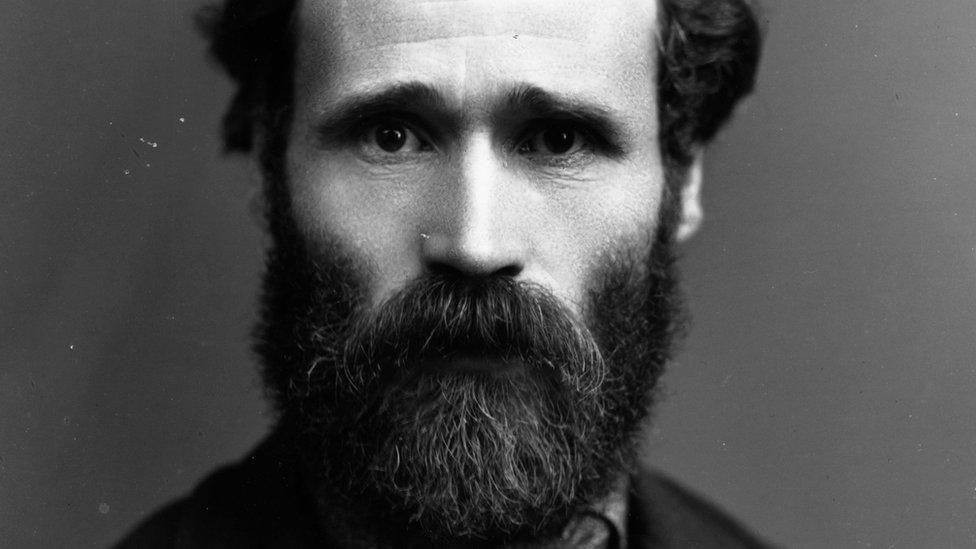

But they found the story of conscientious objection in south Wales could be traced back to Newhouse, Scotland in 1856 - where James Keir Hardie was born.

From the age of 10, he was working underground in a local colliery to support his family.

"People often wonder why he took Wales to his heart but it could have been an incident where a pit shaft collapsed and he was trapped," said the project's Alan Terrell.

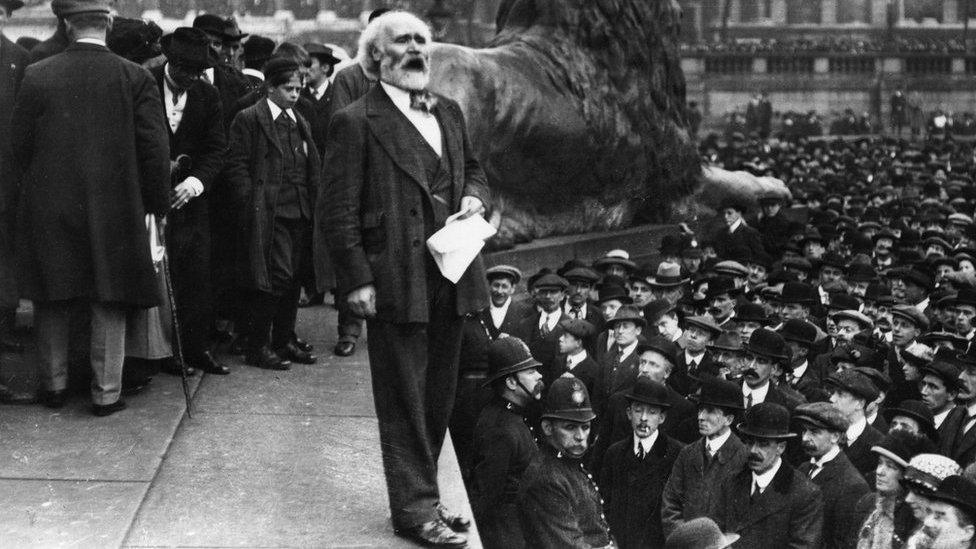

Keir Hardie addressing the Suffragettes' Free Speech meeting in Trafalgar Square in 1913

"Those above threw rocks down and smashed the cage before lowering buckets down to rescue the men.

"But Hardie had gone to sleep in a corner and it was only because his mother was at the top, frantic, they sent someone down to find him."

Mr Terrell said "this camaraderie stuck with him through his life" and while serving as an MP in London, he would ask that condolences were sent to Wales following pit disasters.

In 1894, he attacked the monarchy after Parliament refused to extend sympathies to the families of 251 people killed in a colliery explosion in Cilfynydd as part of a message to the King.

This contributed to him losing his seat, with the mayor of Merthyr Tydfil then asking Hardie to stand to represent the area.

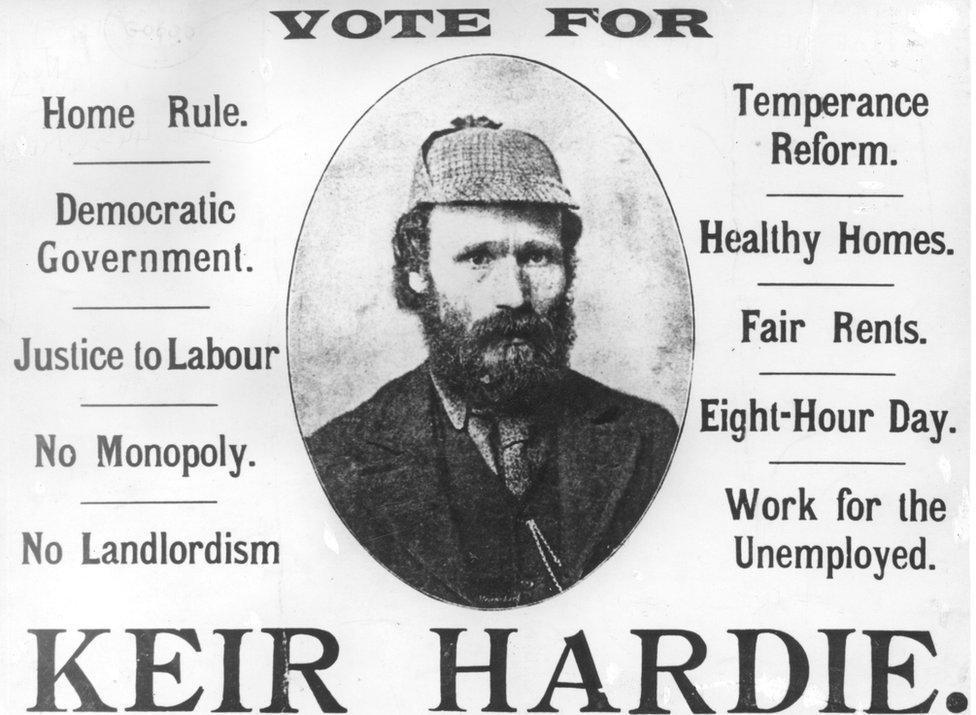

He was duly elected Wales' first independent Labour party MP in 1900 and championed the working man - wearing their Sunday best of tweed jacket and deer stalker to Parliament, rather than the expected top hat and tails.

A campaign poster for Scottish socialist and labour leader Hardie from 1895 lists many workers' issues

Mr Terrell said when war broke out in 1914, support in south Wales for the cause was "about 50-50".

"There were those loyal to king and country, but in areas such as Merthyr and Aberdare, where there was a strong labour presence, socialist background, people thought 'it's not our war'," he said.

"They thought we shouldn't be fighting, it became religion versus politics and it was a melting pot here."

At the heart of the opposition campaigning was Hardie, with some people calling "get the German out" when he spoke.

He had opposed conflict his entire life but died in 1915, aged 59, a year before conscription came in for men, aged 18 to 41.

"He was anti-war, the first objector without knowing it," added Mr Terrell.

"He was very passionate about not going to war - he recognised a lot of people would make a lot of money from it, selling arms, uniforms, horses.

"Hardie saw it as a profiteering exercise as well as a loss of men. He worked himself to death, died of pneumonia and was a broken man as he couldn't stop it."

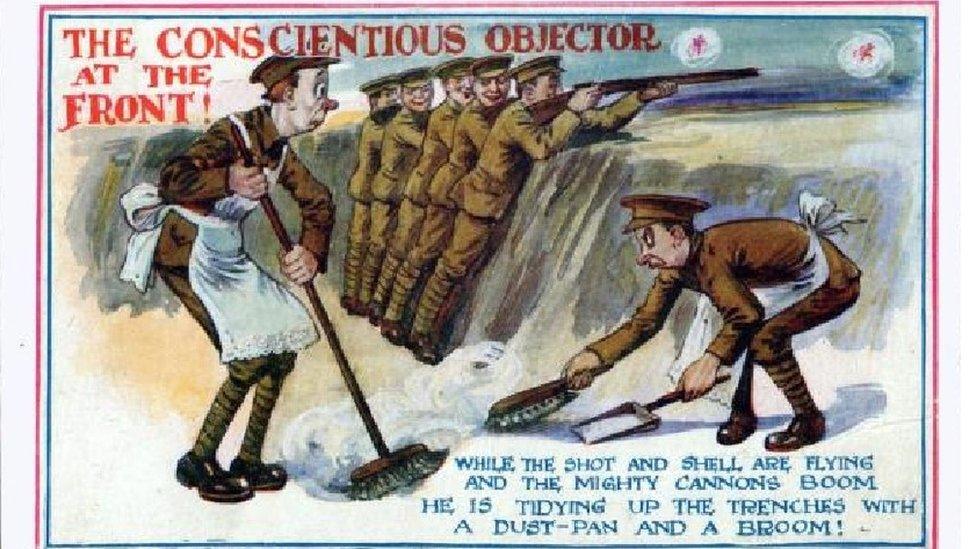

Conscientious objectors who did not want to fight were given other duties such as cleaners and medics at the front, while absolutists refused to play any part

While military conscription for coal workers did not come in until 1918, there were many other men eligible to fight.

Every week, the Police Gazette listed hundreds of men wanted for service, with about 900 conscientious objectors from Wales.

Of these, 25 went on the run to work for the Forestry Commission in the Brecon Beacons, Powys, under false names.

The Merthyr Pioneer reported about a pit boy called Aneurin Bevan, 20, who was excused from duty following a tribunal as he had nystagmus - an involuntary movement of the eyes - in June 1918.

Documents also detailed the case of Sidney and Henry Solomon, Orthodox Jews from Crumlin, Caerphilly county.

They made a vow to their dad on his death bed they would not take any part in the war - and were in jail long after it ended.

But it was not just the working classes who refused to fight - the research also found examples of middle class people excused from service.

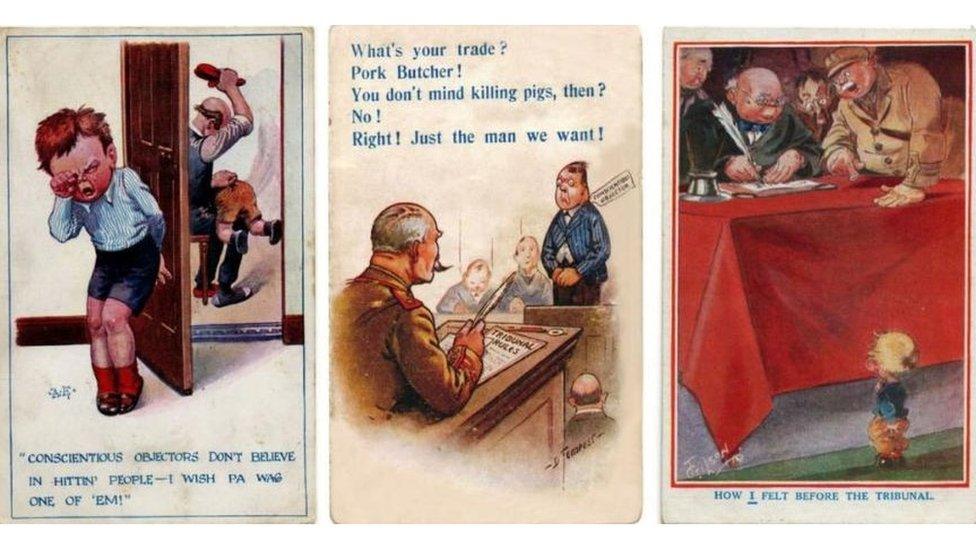

People whose sons and husbands joined the war effort heckled those who refused to fight while posters were made mocking them

"There was a Newport landlord, who owned £14,000 worth of property. He got off maybe because he owned so many businesses, half of the town would've fallen flat," Mr Terrell said.

"Another case was of a man who wound down his dad's undertaking business and became a special constable so he didn't have to go."

Swansea University's Dr Aled Eirug suggested it would have been difficult for many people to fight because of religious beliefs and the commandment "thou shalt not kill".

He said he would have found it "very difficult" to join up himself, but added: "My father was a conscientious objector in the Second World War and my grandfather was a conscientious objector in the First World War, so you could say that the family has form."

Falklands veteran Simon Weston said: "The thought of killing someone, even though I joined the Army and picked up a rifle and was prepared to, it fills me with horror now, and that's why we should not rush to judge people."

Mr Terrell described the period between July 1914 and November 1918 as "one of the darkest of human history" when "a country turned on its own population" for refusing to fight.

But he said the suffering was not totally in vein, with "mistakes rectified" when World War Two broke out in 1939.

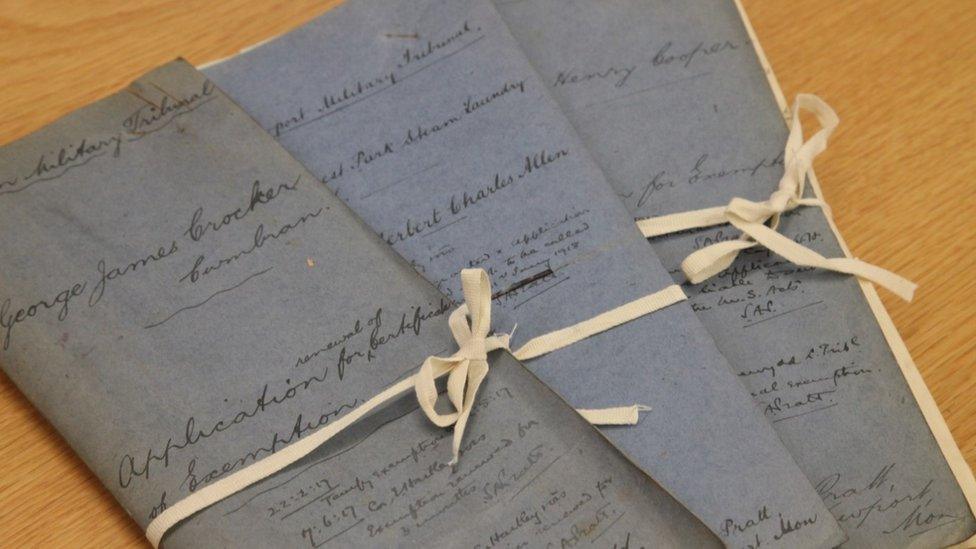

Notes from military tribunals kept at the Gwent Archives, Ebbw Vale

- Published23 August 2017

- Published26 September 2015