Gleision mine deaths: Pit surveyor stopped from doing job, court hears

- Published

Garry Jenkins, 39, Philip Hill, 44, David Powell, 50, and Charles Breslin, 62, were killed in the mine

A mines surveyor gave up his job at a pit almost a decade before four men died there because he was stopped from doing his job properly, a jury heard.

Lee Reynolds suspected illegal workings at Gleision drift mine in the Swansea Valley, Swansea Crown Court was told.

David Powell, 50, Charles Breslin, 62, Philip Hill, 44, and Garry Jenkins, 39, died in 2011 when the mine flooded following the use of explosives.

Malcolm Fyfield and mine owners MNS deny manslaughter charges.

Up to 650,000 gallons of water swept through a closed-off section of the mine, the court has previously been told.

Mr Fyfield was one of seven men working in the mine near Pontardawe at the time and survived after he crawled out through sludge and dirt.

On Tuesday the court heard evidence from surveyor Mr Reynolds, who said his responsibility was to accurately record the workings of the mine.

But the manager at the time Ray Thomas "was not allowing me to do that function", he said. He said his position was "untenable" so he quit in 2002.

The court heard that Mr Reynolds contacted mines inspector Tony Forster following the disaster of 15 September 2011.

Mr Fyfield's barrister, Elwen Evans QC, said: "You knew it was a mine which you had been involved with years before. Presumably you felt it right to inform him of those difficulties?"

'Full of water'

Mr Reynolds responded: "Yes. It may have helped with the operation."

The court was told that Mr Reynolds had described Mr Thomas as dishonest because he would hide the extent of the mine workings from the surveyor.

Mr Thomas would order shots to be fired at the end of a shift so the mine would be full of smoke when Mr Reynolds entered to survey it, the jury heard. This would make his work "nigh on impossible".

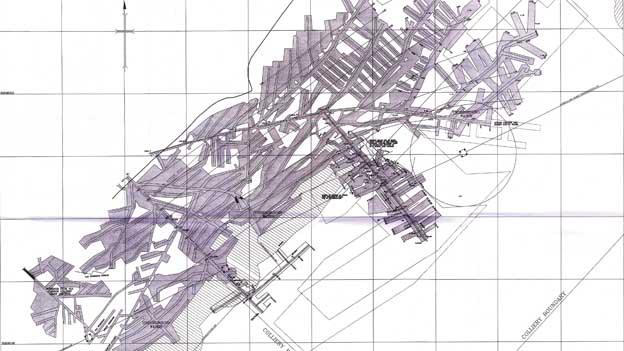

His final map was produced following a survey carried out in January 2002.

Map of the Gleision mine which was shown to jurors during the trial

The jury was told Mr Reynolds suspected there may have been illegal workings at the mine - workings carried out without licence or planning authority.

He said he was aware illegal workings could have an effect "down the line". Asked what he meant by this, Mr Reynolds said because the workings would not be recorded on a map "any third party coming into that area may think there's virgin coal to work" but in fact they could break into old workings which "as in this instance, may be full of water".

Mr Reynolds said he had not been able to measure water levels in a section of the mine because he had been denied access by the manager.

Asked if a lot of the information a surveyor needed was dependent on the mine manager sharing it, Mr Reynolds replied: "Everything."

The court was told earlier that Mr Fyfield had a good reputation for safety.

Ms Evans asked Mr Reynolds whether he knew Mr Fyfield, and he replied: "I had heard of him but hadn't directly worked with him, but knew him by reputation."

'Good reputation'

Ms Evans said: "You knew, for example, that the Health and Safety Executive, when Mr Fyfield was going to take over at Gleision, they were happy because he had such a high reputation?"

"Yes," he replied.

"Having a good reputation is terribly important?" asked Ms Evans. "To some. Some not," he replied.

"Because there are some in the small mines known to cut corners?" Ms Evans asked.

"I have no experience, only of his reputation," said Mr Reynolds.

"But his reputation, was he in the other camp?" she asked. "Yes," he said.

The trial is due to last until at least the end of June.

- Published31 March 2014

- Published31 March 2014

- Published27 March 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published16 December 2013

- Published18 September 2013