Mystery of Laugharne 'French' woman's grave unravelled

- Published

Historian Janet Bradshaw was determined to find out who Leonie Demoulin was

The century-old mystery of "the French woman's" untended grave, in the same churchyard where Dylan Thomas lies, was finally laid to rest on Saturday, with the dedication of a new cross in her memory.

The old, decayed cross stood near the main door of St Martin's Church in Laugharne, Carmarthenshire, and simply read: "Leonie Sohy Demoulin, A Notre Mere, Regrettee."

It has caused intrigue among parishioners for decades, leading historian Janet Bradshaw to try and crack the riddle.

Translated from French the inscription reads: "Leonie Sohy Demoulin, to our mother, lamented."

Mrs Bradshaw's investigations discovered Madame Demoulin had not actually been French at all, but was in fact one of the 250,000 Belgian refugees who sought sanctuary in Britain at the outbreak of World War One.

"I was fascinated yet also saddened at the thought that this 'French woman', as some said she was, had died so far from home," Mrs Bradshaw said.

"Had she been washed ashore from a stricken ship as others before her? Or maybe come to Laugharne as a servant to one of the local gentry? And what about her children? I was determined to find out."

By sending for her death certificate and checking the parish burial records, Mrs Bradshaw discovered that Madame Demoulin was in fact Belgian, had lived with her husband, daughter-in-law and young grandson Rene at The Grist in Laugharne and had died of a heart condition on 17 January 1916 aged 58.

Her home address was given as Berchem, a suburb of the port city of Antwerp, and her funeral was conducted by Father Xavier, a Belgian priest based at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire.

"I kept thinking about poor Monsieur Demoulin having to cope with the death of his wife and being left behind in a strange country, yet frustratingly I could find no further details of their story," she said.

But a breakthrough came when retired teacher Rosemary Rees unearthed photos and documents from the Laugharne Refugee Committee, left to her by her grandfather.

They revealed the Demoulins were among 12 Belgian refugees to arrive in Laugharne in December 1914; among about 5,000 that Wales accepted in total.

Belgian refugees arriving in Rhyl, Denbighshire, during World War One

But while many towns across Britain only wanted to host what was termed at the time "the better class of Belgian", photos and records show that Welsh people came out in their thousands to welcome the most impoverished and vulnerable.

Many graduated towards towns where there was a "pull-factor", such as the 66 who headed to Rhyl where St Mary's Convent already had eight Belgian nuns, and the 762 who went to Swansea, where there was an established Belgian community centred around the zinc smelting industry.

In return for their hosts' kindness, the refugees left behind a legacy of art in the form of a beautiful plaque in Bangor, the carvings at the churches of Llanwenog and Llanfihangel-y-Creuddyn, and the Belgian Pier in Menai Bridge.

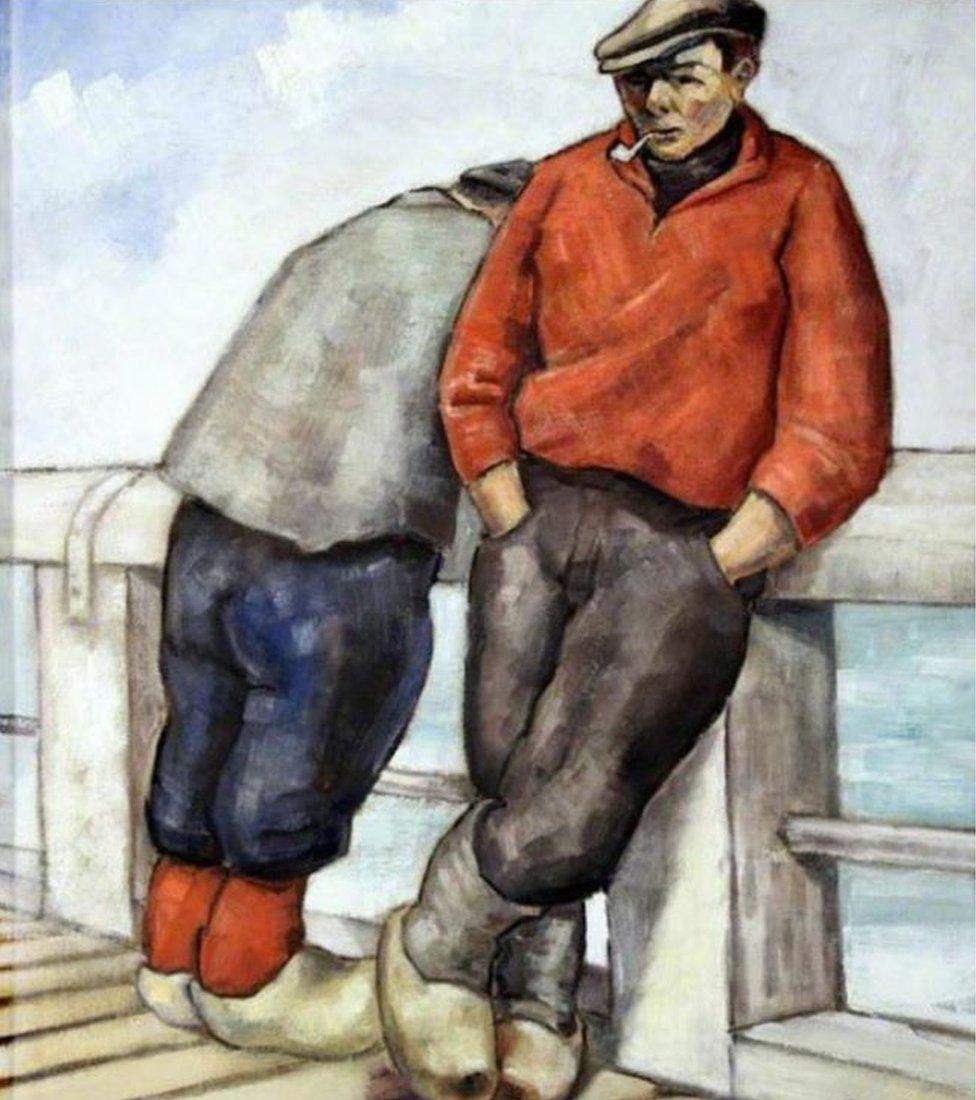

In Swansea, the painting of Two Fishermen of Ostend by Belgian artist Albert Hagers hangs in the city's Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, with an accompanying inscription reading: "A small token of the gratitude of the Belgian government to Swansea for all the kindness shown to the Belgian people who have come to the town over the years."

The painting Two Fishermen of Ostend was given to Swansea by the Belgian government

Although perhaps their most enduring gift was the intricately carved Black Chair, made by Belgian refugee craftsmen and awarded posthumously to Hedd Wyn at the 1917 National Eisteddfod in Birkenhead, following his death at The Battle of Passchendaele.

Dr Christophe Declercq, of University College London and KU Leuven University in Belgium, is the lead academic on World War One Belgian refugees in Britain.

"Wales only received quite a small proportion of all the Belgians to come to Britain, but when we started appealing for family memories we found a disproportionate number came from descendants of people who'd been here," he said.

"Janet Bradshaw's work deserves to be celebrated because here we have another piece in the jigsaw of a unique story of the particularly warm welcome in Wales and the sense of community shown in hosting the newcomers.

"I hope other communities and historians will be inspired by their example and, if they uncover any Belgian refugee stories, will contact me."

M Demoulin left Laugharne shortly after his wife's funeral, though no-one knows where he headed.

The younger Mme Demoulin and her son Rene did not return to Belgium until March 1919.

Photos provided by Rosemary Rees show Rene joined the Belgian army in the 1930s as war once again loomed, but after that the family trail goes cold.

But Leonie Demoulin was remembered in a service on Saturday where Father Christopher Lewis-Jenkins, priest of St Martin's, unveiled a new cross carved by local craftsmen.

- Published9 September 2017

- Published22 May 2016

- Published7 July 2014

- Published15 September 2014