Could Iran's phased plan defuse nuclear standoff?

- Published

- comments

Teams from Iran and six other nations are holding two days of discussions on Iran's nuclear future

GENEVA: So the Iranian Foreign Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has made his PowerPoint presentation and we are now a little wiser about how the long running crisis over the country's nuclear program might be resolved.

As for the detail, even half way through day one of this two-day meeting with representatives of the international community that is not clear, what is though is the vital importance of timing and the need to show progress quickly.

The need for rapid movement in a process that has been going on for so many years is obvious and mutual.

Iran wants swift relief from the sanctions that have laid its economy low; the US and others represented here (UK, France, China, Russia and Germany) have had the feeling that they have been kept dawdling in the negotiating game for years while the Iranians have forged ahead with their nuclear programme.

What Mr Zarif laid out this morning was a three-phase programme designed to deliver a result in one year.

To the extent that it has been possible to discover the details of his presentation from Iranian journalists here: Phase 1 will take up to six months, involving the lifting of sanctions and re-doubled international inspections; Phase 2, which Mr Zarif's officials were reluctant to talk about in detail, dealt with confidence building measures designed to reassure the international community about the peaceful nature of their effort; and Phase 3 an end state is reached in which the country's nuclear project is certified as peaceful by the international community.

Past failure

The Iranian approach emphasises gaining agreement now on that end state - in which Iran would continue to enrich uranium (presumably at markedly lower levels) but as part of a heavily inspected peaceful nuclear programme - so that everyone can understand the direction of travel.

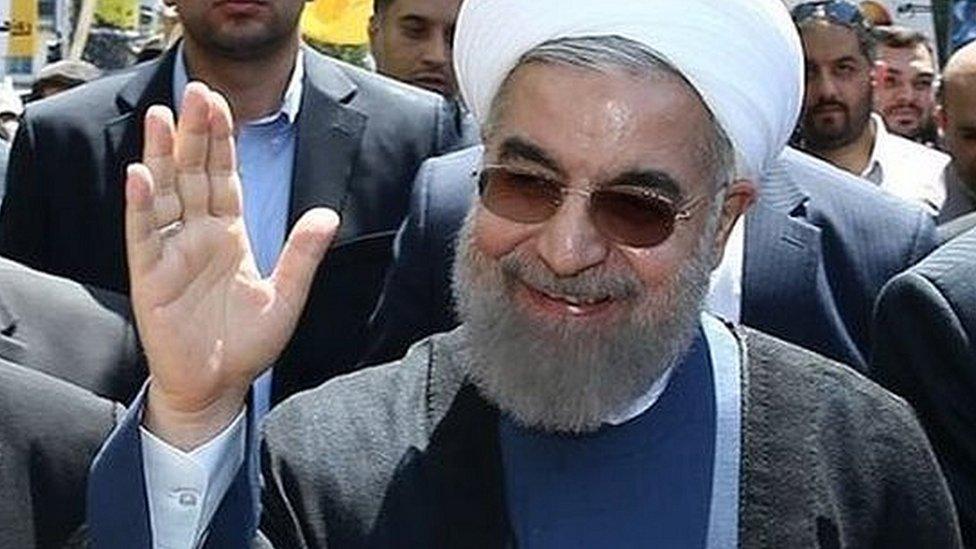

The new Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has himself spent long hours in this negotiating game, and was responsible for a 2003 agreement in which, many of his countrymen feel, much was conceded without Western acceptance of that end point (Iran subsequently broke out of this agreement).

Two things are clear about this approach.

Firstly that if it does indeed involve the outside world switching off sanctions before there is a significant reduction in Iranian nuclear capabilities, it will be very hard for the US to sign up to it.

The second is that this takes longer than the three to six months originally mooted by the new Iranian leadership.

We will just have to wait for more detail on how a phased lifting of sanctions might be meshed in with a halt to Iranian uranium enrichment activities, extended to other atomic activities (such as the commissioning of a new reactor able to produce plutonium) and then an actual dismantling of certain facilities.

In this last context the US has fixed on the recently commissioned underground uranium enrichment facility at Fordo as a particular problem.

Let's assume that such details can be worked out, so long as the White House accepts that Iran will retain the ability to enrich its own fuel and hangs on to the stockpile of material that has already been produced. These are reasonable assumptions in terms of the White House, but the same cannot be assumed of Congress where scepticism about Iranian intentions remains high.

If all this can be done, it could take a while and the timescale issue still remains key. The longer the negotiating process goes on, the greater the sceptics in both camps will be empowered.

Mr Rouhani's critics will label him naive for assuming there could be any rapid lifting of US and EU sanctions (the ones that really hurt, on the banking and oil sectors) and members of the US Congress who feel that the world has been led a merry dance this last 10 years will insist that they have been vindicated.

That is why quick progress is so vital, and it is also why today those on the other side of the table have been reluctant to criticise Mr Zarif's presentation of Tuesday morning without hearing further details, lest such action cause an immediate loss of momentum.

- Published15 October 2013

- Published14 July 2015

- Published20 May 2017