The North Korean defectors who want to return home

- Published

The Korean border is heavily guarded on both sides

In the past two decades thousands of North Koreans have fled their homeland, seeking refuge in the South. So why are some now deciding to return?

Kim Hyung-deok met his wife at South Korea's top university, has two children and a successful career. He has a house in the countryside outside Seoul and a taste for sharp suits.

Hyung-deok was born in North Korea, but about 20 years ago escaped to the South. He is one of about 25,000 to do so in the past two decades.

It is a long and dangerous journey, but once defectors arrive South Korean citizenship is guaranteed.

Yet a small number, Hyung-deok among them, are intent on returning to their repressive homeland.

Family separations

"It might look as if I've succeeded in South Korea," Hyung-deok says, "but I haven't really, because my parents and siblings are still in the North, and I haven't been able to see them.

"It's only natural for me to try to find ways to visit North Korea - openly and legally."

A few years ago, Hyung-deok travelled to the North Korean embassy in China and said he wanted to go back for a "holiday".

"At the time, relations between the two Koreas were quite good, and South Koreans were able to visit North Korea," he says.

Kim Hyung-deok escaped to South Korea 20 years ago

"Yet no-one who actually came from the North had tried to do it - I was the first. When they learned that I was a defector, they got very angry."

Hyung-deok says that he is planning another attempt to enter North Korea next year.

It is illegal for South Korean citizens, including defectors, to have any direct contact with the North - no phone calls, no emails, no letters.

Defectors with family left behind often push for warmer relations between the two governments, in the hope of seeing them again.

River crossing

Because of the tightly-patrolled frontier between the two Koreas, most fugitives from the North escape across the river border with China.

That's also where Kim Gwang-ho arrived, 18 months ago, but to re-defect to North Korea.

Gwang-ho had left South Korea after getting into financial difficulty. His plan was to swim across the river, but he had his wife and child with him and decided the current was too strong.

So instead he visited the North Korean consulate. It took him a week to persuade them he was serious.

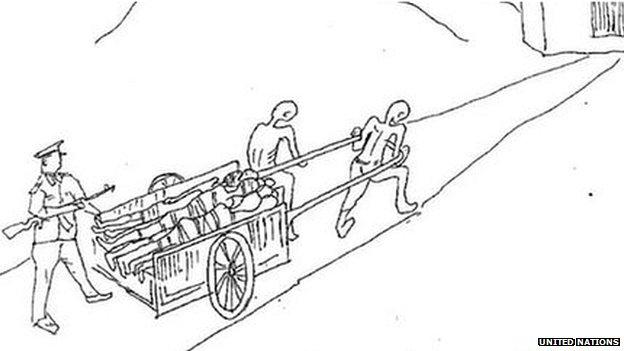

A defector describes life in a North Korean prison camp

Gwang-ho and his family were taken to Pyongyang and paraded in front of a press conference organised by the regime.

He said people who escaped to South Korea were the "victims of human rights activists, conspiring against the North Korean state".

South Korean government figures state that 13 defectors have returned to the North since they started arriving in the South 20 years ago, but activists say many more have re-defected unofficially.

There are questions over whether the North Korean state has a role in forcing people to return, and defectors in the South fear what sort of information might be passed on by those going back.

For Gwang-ho, initially it seemed life in the South was a distant memory - its capitalist democracy reviled and criticised. But a few months later, he decided he wanted to go back.

'Desperate story'

However, once there, he was hauled in front of a South Korean judge and asked about his erratic behaviour.

His lawyer cited financial problems in the North. Other reports suggest he feared for his safety. The court jailed him for three years for "entering North Korea and revealing classified information about other defectors, and about South Korea's methods of investigation".

The BBC was denied permission to visit Gwang-ho.

We wrote to him instead and, in his reply, he explained that the press conferences arranged by North Korea to showcase returned defectors are compulsory. This is my "real and desperate story", he wrote.

Finding a place in South Korean society is not easy for defectors.

Inmates' drawings have captured scenes from North Korean prison camps

Unemployment among them is more than three times the national average. Some surveys suggest more than half experience depression, and that 25-30% of young defectors have considered leaving South Korea because they feel they don't fit in.

Like other defectors, Son Jung-hun got a package of government support on arrival in South Korea, including a flat. But debt problems have meant bailiffs have taken his fridge and washing machine. Now, his meagre food rations are stored on the unheated balcony.

Jung-hun has appealed to the South Korean government for official permission to return home.

'Eating rats'

"Over the years I've noticed the political indifference towards defectors here in the South," he tells me.

"There have been days when I ask myself why I chose to come here in the first place. Anywhere a North Korean defector goes, he could face difficulties and discrimination."

But, for every defector returning home, many thousands more have no intention of ever going back, saying they suffered harsh punishment and repression in their homeland.

One North Korean defector I met fled to Seoul a year ago, after she was released from imprisonment at North Korea's prison camp Number 12. She had been held after exchanging some foreign currency with a Japanese national and accused of espionage.

The woman describes seeing large maggots crawling around the camp that had grown out of corpses.

"People would dash for them, grab them and put them in their pockets. Later, they would eat them," she says.

Watch Lucy Williamson's Newsnight film on the North Korean defectors longing for home

"Others would capture rats and eat them raw. I remember their mouths covered in blood. I saw so many people killed for breaking very minor rules. In my cell alone, three people were killed within a month."

UN investigators recently found "abundant evidence of crimes against humanity" committed by the regime, and said North Korea should face international justice.

North Korea denies allegations of torture made by defectors, and the existence of prison camps, and refused to allow UN investigators access to the country to gather evidence.

When the first defector from the North arrived in South Korea 20 years ago, there were huge celebrations, and huge expectations.

Both governments talk about the need for reunification, but the lesson provided by South Korea's defectors is stark - if integrating 20,000 North Koreans is so difficult, what will happen when it's time to absorb 20 million of them?

- Published22 November 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published23 April 2013

- Published25 April 2012