How easy is it to be a drugs cheat in sport?

- Published

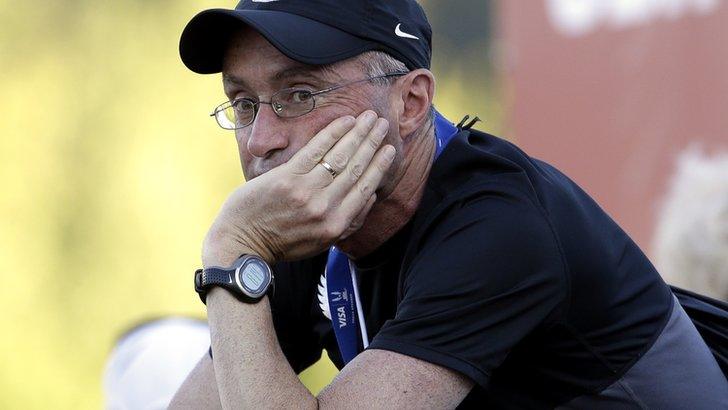

Anti-doping agencies in Britain and the US have begun investigations into the American coach Alberto Salazar,, external who is accused of giving performance enhancing drugs to his athletes.

He has denied the allegations in a 12,000-word open letter, but the scandal has put the spotlight back on doping in sport.

Four experts give their perspective on how easy it is to cheat to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme.

Michele Verroken: Cat and mouse game

Former international korfball player Michele Verroken ran the UK's anti-doping organisation between 1986 and 2004. She is now director of the Sporting Integrity consultancy.

"I oversaw the introduction of the very first quality-assured anti-doping programme in the world, and then the introduction of the world anti-doping code.

"There are stimulants which increase awareness, alertness, reaction time of the body, narcotics and pain relievers.

"We have hormone substances, from the synthetic anabolic steroids right through to ways to increase the body's own testosterone level or even the body's own red blood cell count to offset the onset of fatigue, so you recover more quickly in order to train again earlier.

"[Some athletes] take out a quantity of their own blood and re-infuse the red blood cells to get the benefits. We've known athletes to have a training buddy who's got a similar blood group so that they could use their blood as well.

The bottles which need to be filled when a doping control officer arrives for an unannounced test

"The testing process has had to involve the observation of athletes providing samples because of the manipulation techniques that have gone on: you can buy a prosthetic penis in order to provide a fake urine sample.

"At the moment elite athletes are signed into a programme called Whereabouts. They must give one specific hour where they definitely could be found if the anti-doping authorities want them. Seven days a week, 52 weeks of the year.

"It is still a cat and mouse game that we're playing: I've received postcards and anonymous messages saying 'bet you can't catch me'."

Professor David Cowan: We catch cheaters in the end

Professor David Cowan is director of the Drug Control Centre at King's College London. He ran London 2012's anti-doping laboratory in Harlow.

"During the games I was responsible for 400 people. We tested more than 6,000 samples. The turnaround time was one working day.

"We have analytical methods that are second to none. We can find drugs in a sample very easily, provided we've got a reliable sample, taken at the right time.

"[We have to make sure] that what we found didn't get into your body just by you holding a handrail on a bus and then touching your mouth, or that it's maybe a minor contaminant in food.

"[We also have to prove] the administration of something the body produces naturally. In its simplest form we all produce testosterone, how do we know if someone hasn't injected some testosterone, as distinct from just being a person who produces large amounts?

"When we analyse a sample, we run it through a technique called chromatography. Many of us learnt in school that if we get a stain on clothing, it spreads out and you see a separation of colours, that's chromatography.

Inside the Olympic drug-testing lab

"A more sophisticated form of that is high performance liquid chromatography. We put the sample into an area and separate it out in space. The mass spectrometer then works out how many carbons there are in the molecule, how many hydrogens, how many oxygens; and starts to build up the complete structure.

"The great majority of substances will certainly [be identified]. Never say never to a scientist because a good scientist will always allow the remote possibility [of unknowns]. But I question whether we are always one step behind.

"I think it's fairly level at the moment. Pharmaceutical companies are actually informing the World Anti-Doping Agency, external of drugs in their pipeline, long before they can get into the hands of the cheaters.

"How do we know whether we're working or not? The cheating athlete keeps cheating. We catch up with them in the end."

Victor Conte: It's still easy to dope

Victor Conte supplied prohibited supplements and hormones to Olympic medallists, baseball players and American footballers via the Balco sports supplement lab he founded in California. He now works with anti-doping authorities.

"Initially we did blood testing to develop individualised nutrition programmes for elite athletes, and it had nothing to do with illegal performance enhancing drugs.

"But once I realised that pretty much everybody was in on it, I made that decision to join the culture.

"I got this substance from an organic chemist called 'the clear', an oral substance that you put under your tongue with a dropper, and I was the initial guinea pig. I took it myself for four consecutive days, and then I began giving it to a variety of athletes, [American] football players and others.

"It enhanced recovery. Anabolic steroids are recovery drugs. They enable you to train very strenuously - which creates micro-tears and cuts in the muscle tissue - and then you bathe this in nitrogen that comes from the steroid, and it accelerates repair. It enables you to get back to training again: where it would maybe take you two to three days for recovery, you can recover in a day."

Dwain Chambers won the men's 100m final at the European Championships in 2002

He supplied other performance enhancing drugs too - such as fast-acting insulin, growth hormones, and thyroid medication - to more than 20 athletes. The results were immediate.

"Before using 'the clear' and other performance enhancing substances, sprinter Kelli White , externalhad a personal best in the 100 metres of 11.19 seconds. After using a variety of drugs in 2003 she ran a 10.85 secs. So yes, it's very powerful."

In 2002, he met the British track sprinter Dwain Chambers in Miami.

"I had a little chat with him, and told him the ABCs of what goes on at the elite level of sprinting. And the choice was made for him to try this."

That year, with the help of Conte's drugs, Chambers won the 100m at the European Championships in Munich. But the authorities were closing in.

"They had my laboratory under surveillance for about a year, and they were dumpster diving - collecting information out of our trash - and they raided my laboratory and my home on that infamous day, September 3, 2003."

Conte was arrested and jailed for four months., external Soon after, a Chambers sample was re-tested and found to be positive for banned substances., external He was banned for two years.

When Conte left prison, he detailed what he had given Chambers: "the clear" steroid on Mondays and Wednesdays, testosterone cream on Tuesdays and Thursdays and a hormone called EPO on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

"If they're going to use a fast-acting testosterone, a gel, a cream, they do it at night. One study showed you could take 40 milligrams of oral testosterone, and it will peak in your bloodstream and then go back down within six hours. So they're using these drugs at night, and by the time testers show up in the morning, they test negative.

"It's very easy to dope in sport now. There's all sorts of things that athletes can do to circumvent [the rules], and there's nothing they can do about it."

Professor Susan Backhouse: We need to understand why people dope

Former discus thrower Professor Susan Backhouse is head of the Centre for Sports Performance at Leeds Beckett University.

"We've done surveys with athletes at all levels: coaches, other athlete support personnel, support and exercise scientists, medical professionals. Athletes' willingness to dope appears to follow periods of instability. It might be following an injury, where they are in a career transition or if funding is at risk.

Lance Armstrong was stripped of his seven Tour de France titles by US anti-doping authorities in 2012

"The athlete's support network is based on trust, particularly between the athlete and the coach. And, in addition to explicitly encouraging or facilitating doping, we have in the past had cases where coaches have actually deceived sports people into doping.

"The rewards of success are very tangible. There are clear links between those succeeding in the Olympics and medalling and the sponsorship that flows their way. There's also the element of remaining on contracts.

"There's definitely a relationship between the perception of use and then an individual's willingness to use. So what we do need to do is highlight the fact that not everyone is doping, particularly when we're talking to young athletes.

"Media headlines - which are fairly frequent in the context of drugs in sport - lead to the perception that it's really widespread. But quite simply at this moment in time we've got no way of knowing how widespread it is."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Attribution

- Published30 June 2015

- Published26 June 2015

- Attribution

- Published19 June 2015

- Attribution

- Published18 June 2015

- Published30 December 2014

- Published1 September 2014

- Published9 October 2013