Widespread revolt against the political centre

- Published

The far right in Austria has attracted widespread support

On both sides of the Atlantic, liberal democracy is on the defensive.

Post-War politics, built on a moderate consensus, is under strain.

The centre is holding but only just.

Austrians in large numbers voted for a far-right candidate in the face of much of Europe warning against allowing the first right-wing populist to become head of state since World War Two.

The strong showing of a candidate from the Austrian Freedom Party joins the anti-establishment success of Donald Trump in America.

In France, Marine Le Pen's National Front party has regularly topped some of the polls.

Although traditional parties appear embattled, the mainstream has proved resilient.

The London mayoral elections and the general election outside of Scotland were old-fashioned contests between Labour and Conservative.

In the last European elections, there were successes for anti-establishment parties - but power firmly remains with the centre-right European People's Party and the Socialists and Liberals.

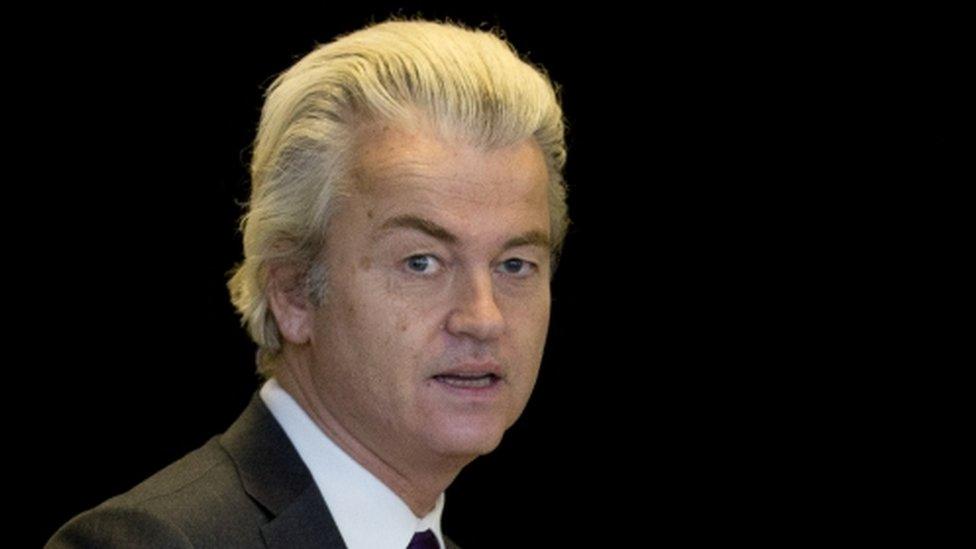

In the Netherlands, the populist politician Geert Wilders topped the polls but stumbled in the general election.

Geert Wilders failed to win the Dutch general election

In France, the National Front performed strongly in the recent regional elections but failed to make a breakthrough in the all-important second round of voting.

More often than not, the story in Europe is of the outsiders, the upstarts, the captains of the resentful rattling the gates but rarely being entrusted with power.

In Greece, there have been often violent protests against austerity, seen as imposed from Brussels - but when asked whether they wanted to leave the EU, fewer than 40% agreed.

In Hungary and Poland, however, there are now parties in power prepared to challenge the European consensus and politics as usual.

Austria 'rejects far-right president'

Is Europe lurching to the far right?

Guide to nationalist parties challenging Europe

And, in America, Donald Trump has tapped into the current mood of discontent.

He has defied all those who believed that the former Reality TV star would flame out and old politics would resume.

It hasn't, and politicians in Europe are watching America anxiously.

What is the reason?

So what is driving this?

First, the politics of 2016 are still being defined by the financial crash of 2008.

Many middle-class Americans are working longer for less income than they earned decades before.

The numbers who call themselves middle-class are shrinking.

In the past six years, the US has created an impressive 14 million new jobs - but it is what those jobs are paying that gives politicians such as Mr Trump his opening.

Bernie Sanders has tapped into anger about inequality in society

In a time of economic insecurity, inequality has increased.

Inequality fosters mistrust of the elite.

In the US, there is a residual dislike of Wall Street and the bankers.

It has fuelled the success of the campaign of Bernie Sanders, an outsider candidate, who describes himself as a democratic socialist.

One of the marks of this new politics is a hostility to trade agreements that are seen as having stripped out jobs from America.

Even Hillary Clinton has had to appear lukewarm , externalabout signing future trade deals.

All the indications are of an electorate losing faith in public institutions.

Europe has been less successful at creating new jobs, and youth unemployment in many countries has remained stubbornly high.

It has stoked fears of Europe as a low-growth region.

Here, too, there is a protectionist streak running through the anti-establishment campaigns.

And the migrant crisis has fed the mood of insecurity.

Two narratives

There are really two narratives competing with each other.

One sees itself as outward-looking, internationalist, at ease with a globalised world.

It is more inclined to embrace migration as the mark of an open culture.

In place of one identity linked to a nation state, they speak of multiple identities.

It believes that globalisation cannot be slowed or reversed.

Three decades ago, there were no smart phones.

Now, there are more than billion, and technology is both connecting and shrinking how we live.

Donald Trump has inspired his supporters with his attacks on the political mainstream

They tend to see institutions such as the EU protecting smaller countries and giving them influence.

Even though many manufacturing jobs have migrated to Asia, they argue that international trade benefits consumers and producers.

The other narrative is that globalisation has damaged the interests of working people, with jobs moving elsewhere.

Migration, for them, puts pressure on wages, increases demand for public services and dilutes the identity of long-standing communities.

They believe democracy has been undermined and that parliaments need to recover their authority.

The restlessness among voters on both sides of the Atlantic is rooted in the powerlessness of those in power.

Politicians seem unable to respond to demands of the voters.

In Europe, they struggle to deliver new jobs for young people.

Those in power often doubt the policy of austerity, in private, but have to enforce it.

Increasingly, it seems that decisions are decided by remote masters.

These same politicians are no longer trusted to deal with implications of automation and robotics on the world of work.

The populists at the gates of power, with their offer of "strong" leadership, promise to regain control of decisions made and that the certainties of the past can be reclaimed.

The challenge for mainstream parties is to convince voters they can deliver security in the face of global challenges; that migration can be managed; that institutions can protect voters from the harsh winds of globalisation; that identity will not be threatened.

In this debate, Donald Trump understands that social media gives him the opportunity to amplify the culture of complaint without the cross-examination of the mainstream media.