New UN chief Antonio Guterres will listen to the world

- Published

Securing an end to the conflict in Syria has been identified by Mr Guterres as a priority

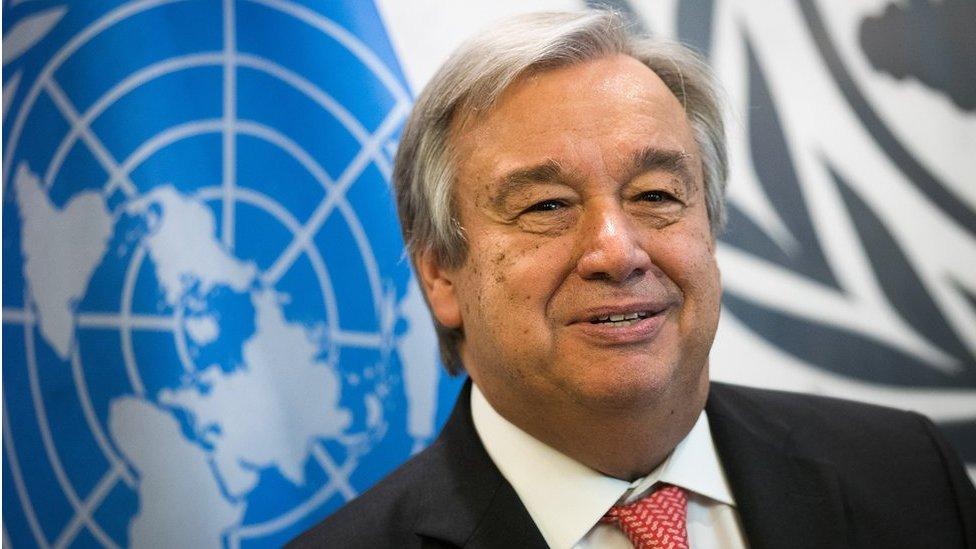

Talk to people who know Antonio Guterres and you hear the same refrain - the newly elected UN secretary general is a very good listener.

"He has this ability to stand his ground on important issues but still make you feel he's heard and understood your point of view," reflects Ninette Kelley who now heads the New York office of the UN's Refugee Agency, UNHCR.

Other staff are equally complimentary.

"His background - from heading the Socialist International to leading a Nato nation like Portugal - meant he was welcome everywhere including Moscow, Beijing, and Washington," recounts Melissa Fleming, a key adviser on Mr Guterres' transition team, when we meet on the day he is unanimously approved by the UN's General Assembly.

She pays tribute to him on her Facebook page,, external describing the energy in the hall on that day as "high and hopeful".

Now, to succeed, the world's top diplomat needs people to listen to him.

"We are facing a very difficult moment in our history," Mr Guterres told me just after his thunderous welcome in the General Assembly last week. "It's dangerous for everybody."

And then his plea to the world's powerful players before he takes charge on 1 January: "I call on everyone with influence to put aside their different interests and understand their shared interest is in ending the Syrian conflict and all the conflicts linked to it."

Mr Guterres will need all his powers of diplomacy to be successful in his new job

The new secretary general is expected to pay particular attention to Aleppo, which exemplifies the world's failure to stop Syria's shocking spiral into destruction and despair

John Kerry (right) and Sergei Lavrov (left) have negotiated for months on how to bridge the Syria divide

But behind his clarion call, there's an experienced operator who knows the score.

A year ago, I ran into Mr Guterres as he walked alone in the winding corridors of the UN's headquarters after what had been billed as a major meeting to tackle the global refugee crisis.

"How did it go?" I asked.

The expression on the face of the UN's refugees chief said it all.

"There's just talk, no plan," he replied, shaking his head, visibly angry and clearly exhausted.

His is a face the world recognises: For his tough language on refugees and the world's responsibilities; the warm smile of a respected humanitarian actor, the persistence of someone who now calls himself a bridge builder.

Last Thursday, he stood for nearly two hours in the mother of all receiving lines - the UN's 193 countries all wanted their first handshake with the man of the moment.

Ambassadors will soon be calling on him to press long-standing demands for UN reform and accountability in peacekeeping - just two of the issues on Mr Guterres' agenda.

He will need to be a champion of the UN's sustainable development goals, the barometer of progress in improving people's lives - including his own goal to promote opportunities for women and girls.

There are gains to build on too. On Ban Ki-moon's watch, there's been the historic Paris pact on climate change and progress since then.

Agony of Aleppo

But if climate change is seen as Mr Ban's signature issue, there's already talk that his successor's defining issue will be trying to end major conflicts of our time.

Another goal of Mr Guterres is to promote opportunities for women and girls

Representatives of all of the the UN's 193 countries were eager for their first handshake with the man of the moment

Mr Guterres speaks of a "surge in diplomacy for peace" and acknowledges that his first and biggest challenge will be Syria.

The agony of Aleppo now symbolises Syria's tragic fate. It also exemplifies the world's failure to stop its shocking spiral into destruction and despair.

"The UN has demonstrated a spectacular inability to protect civilians from attack," regrets Jan Egeland, the head of the Norwegian Refugee Council and a senior UN adviser.

"With his experience, Antonio Guterres can change that," he tells me optimistically. "War crimes must be documented and impunity must end."

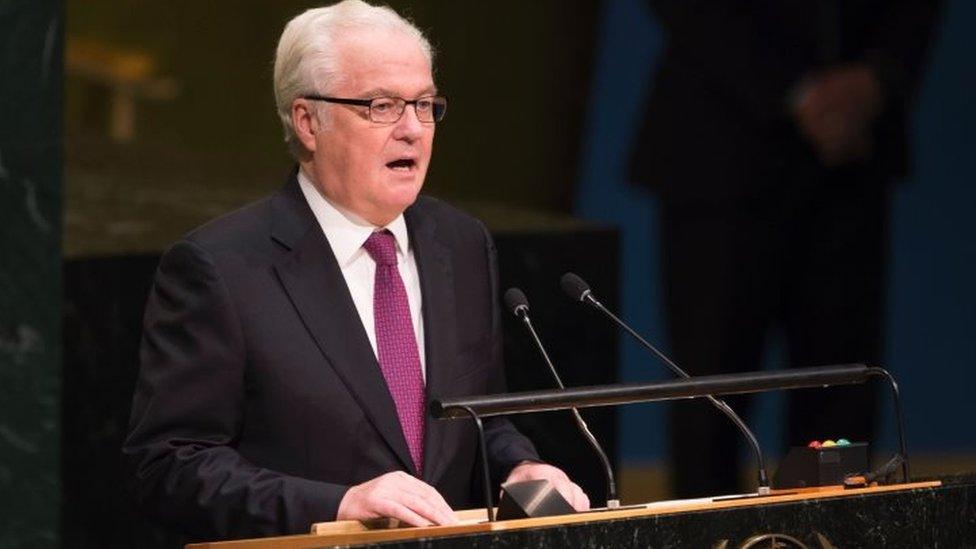

Russian ambassador to the UN Vitaly Churkin has dismissed calls from Western capitals for war crimes investigations, suggesting they should start by looking into their own

But there's scepticism too. "I fear we may have an efficient politician, not a leader," remarks a senior Western official.

"But Kofi Annan became a different man so one must hope," he adds, referring to the former UN secretary general who's still a leading voice on many global issues.

Mr Guterres inherits the world's top diplomatic job at a time when the tools to shape a better world have never been so sharp: an International Criminal Court; a wide array of human rights defenders; unprecedented information flows, including satellite imagery, to document what happens on the ground.

But what many see as possible war crimes in the attacks in east Aleppo, the Syrian government and its Russian and Iranian allies see as an urgent and legitimate assault on groups linked to al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State.

America's John Kerry and Russia's Sergei Lavrov have negotiated for months on how to bridge that divide, and still have not succeeded. It is still not clear what bridge Mr Guterres can build.

The UN's frustrated Syria envoys, from Kofi Annan to Lakhdar Brahimi and Staffan de Mistura, have all cited gridlock in the Security Council, the UN's most powerful political body, as a major part of their failure to bring peace.

Only days after a rare show of unity to support Mr Guterres' nomination, the council was again a political battleground with two rival resolutions to end Syria's war.

Russia's Vitaly Churkin called it one of the "strangest spectacles". Britain's ambassador Matthew Rycroft described Moscow's veto, its fifth in as many years, as a "sham".

"If civilian casualties are caused by Russian bombing, we express incredible regret," Ambassador Churkin tells me in an interview in New York.

But he insists questions have to be asked whether hospitals which come under repeated attack are being used for military purposes, and he dismisses calls from Western capitals for war crimes investigations, suggesting they should start by looking into their own.

For years, Mr Guterres' mantra was "there is no humanitarian solution for a political crisis - there must be a political solution".

The new secretary general knows the enormity of his task.

He will start by doing what he has said to be good at: Listening. But he knows his success or failure ultimately rests on the many countries who all tell him he is the right man for this toughest of jobs.

- Published14 October 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published5 October 2016