Why wasn't a woman elected as UN secretary general?

- Published

Candidates Irina Bokova (l), Unesco chief; Helen Clark(c), former New Zealand PM; Kristalina Georgieva (r), European commissioner for budget and human resources

Antonio Guterres has emerged as the likely man to become next UN secretary general.

A former Portuguese prime minister and head of the UN refugee agency, he was the Security Council's unanimous choice.

A final decision will be made in a formal vote at the council before going to the General Assembly.

But despite Mr Guterres' breadth of appeal and experience, many had hoped the top job would go to a woman.

Out of 13 candidates, seven were women; some arguably even more experienced than Mr Guterres.

Female contenders in the race included the former prime minister of New Zealand, the director general of cultural agency Unesco, the Moldovan deputy prime minister and a senior EU official.

In August, the outgoing UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, said it was "high time" for a female head, after more than 70 years of the UN and eight male leaders.

But those who wanted to see a woman elected were disappointed by Wednesday's result, calling it a "disaster for gender equality".

The Campaign to Elect a Woman UN Secretary-General, a group of mostly academics who supported the female candidates up for nomination, called it an "outrage".

"There were seven outstanding female candidates and in the end it appears they were never seriously considered," the campaigners said in a statement., external

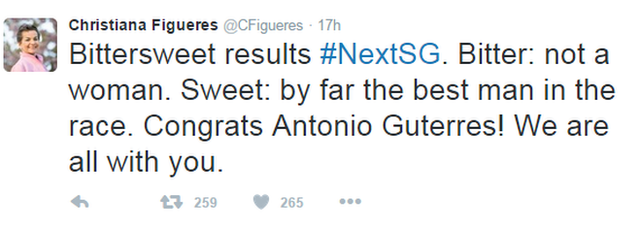

One of the contenders, Christiana Figueres, a key architect of the global climate change agreement signed in Paris last year, called the result "bittersweet".

So was the election sexist?

Some of the candidates have said gender was a factor.

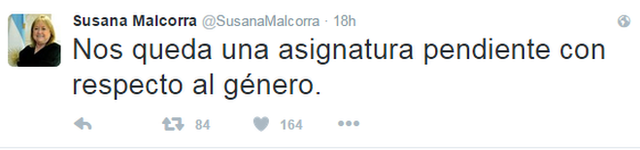

Susana Malcorra, Argentina's foreign minister, complained last month that women did not have a chance in the Security Council.

"It's not a glass ceiling; it's a steel ceiling," she said, according to Foreign Policy, external magazine.

On Wednesday, after congratulating her rival on his win on Twitter, Ms Malcorra went on to say that gender remains an issue in the election of a secretary general.

"It remains a pending issue with respect to gender"

But other candidates downplayed the role of sexism or gender in the race.

Helen Clark, New Zealand's former prime minister, told the Guardian, external: "If you're asking whether women are being discriminated against - no.

"There are a lot of factors swirling around. There is east-west, there is north-south, there's the style of what's wanted in the job. Do they want strong leadership? Do they want malleable? It's all cross-cutting and we don't know what will come in the wash."

What are some of the "swirling factors"?

Some say that, whether you are a male or female candidate, politicking and so-called backroom deals are the biggest factors in determining who is finally nominated.

The Woman SG Campaign said in its statement that this week's result "represents the usual backroom deals that still prevail at the UN".

The UN Association, external in the UK detailed on its website some of the closed-door deals that go on in the UN Security Council.

"One of the most visible types of backroom deals was articulated by UN inspectors in 2011 when they wrote that 'no Secretary-General had been immune to political pressure' to reserve certain top UN jobs for certain member states.

"This refers to the unfortunate practice of major powers extracting promises from candidates in return for their support."

Politico, external highlighted the importance of these dealings as heavyweights like Russia and the US hold immense power to stop a candidacy.

"Whoever wins the race will have had to carefully negotiate the support (or at least avoid the opposition) of both the United States and Russia."

There is no suggestion that any backroom deals were made over the election of Mr Guterres.

Indeed, Samantha Power, the US representative to the UN, described the result as "remarkably" uncontroversial, calling him a candidate "whose experience, vision, and versatility across a range of areas proved compelling".

But it is clear that if a woman is to be elected to the UN's top job next time, it is not just sexism she will have to overcome.

- Published16 August 2016