The rise and rise of the referendum

- Published

Referendums are on the rise across the world. From New Zealand to Colombia, governments are putting more and more big decisions to the popular vote.

When UK voters backed Brexit in June, it prompted a wave of interest in direct democracy - and the unexpected results it can unleash.

This mood has now been enhanced by Italy's emphatic rejection of Prime Minister Matteo Renzi's referendum on constitutional reform.

So what is driving this urge to ask the public their opinion?

Referendums have been called on issues as diverse as peace deals, nuclear power, and whether New Zealand should change the national flag

Why so many referendums?

According to Marco Goldoni, a senior lecturer at the University of Glasgow, we can thank "the limits and crisis of contemporary representative democracy", in which voters see their leaders as out of touch with their lives and feelings.

Referendums are often called when politicians lack the confidence to push through a major change - or are on a mission to do so. Britain's post-war Prime Minister Clement Attlee called them "a device of dictators and demagogues".

It is an accusation levelled at Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who is seeking support for a crackdown on opposition supporters that has seen tens of thousands arrested since July.

Mr Erdogan wants Turkey to vote on reinstating the death penalty, backing or scrapping talks on EU membership, and changing the constitution in his favour.

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wants a referendum on reinstating the death penalty

Alternatively, public votes can be used to create energy around a movement - as with the Scottish National Party (SNP), which campaigns for independence from the UK.

Though Scots voted against independence in 2014 by 55.3% to 44.7%, the SNP is poised to demand a second referendum whenever the political climate favours it.

Nicola Sturgeon, leader of the Scottish National Party, wants another referendum on Scottish independence

Elsewhere, plebiscites are being called to settle questions of historic significance.

Colombia held a referendum on a longed-for peace deal in October, with voters rejecting it in a shock result.

In New Zealand, the government spent NZ$26m (£12m; $17m) asking the people whether to change the national flag.

Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos (left and centre) and the head of the Farc guerrillas Timoleon Jimenez shook hands over the historic peace deal

Can promising a referendum get you elected?

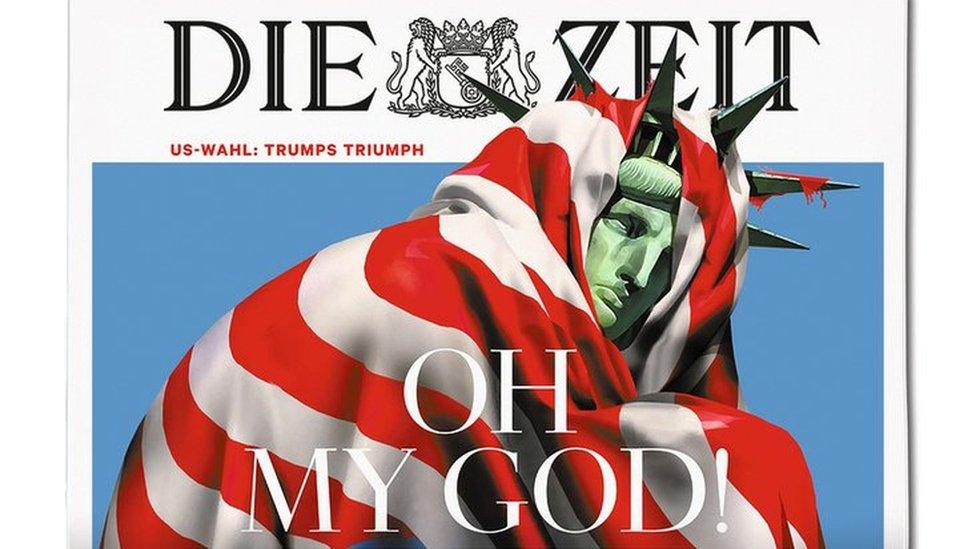

In France and the Netherlands, populist right-wingers think it can.

Marine Le Pen, leader of France's far-right Front National, has promised voters an EU referendum on "Frexit" if she wins the presidency next year.

WATCH: France's National Front leader Marine Le Pen says she wants legislative, territorial, economic and monetary sovereignty all returned to France

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders of the far-right Dutch Freedom party, a vocal opponent of Islam, has reframed Donald Trump's election slogan as "Make The Netherlands Great Again" and promised a referendum on Dutch EU membership if he is elected prime minister in March.

Opinion polls suggest the party could double its representation in the lower house of parliament.

Marine Le Pen (left), head of France's National Front, shares the same referendum goal as the Netherlands' Geert Wilders

So what's the appeal of referendums?

Ahead of the UK's last general election, the three main political parties - Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats - all wanted to stay in Europe but, as the Brexit vote showed, 17.4 million people had other ideas.

Vernon Bogdanor, a professor at King's College London, told the BBC: "People feel that indirect democracy keeps them too far away from any influence.

"The parties are whipped and don't necessarily follow popular views."

The Italian vote on 4 December followed a similar pattern.

Exit from the EU was not on the agenda, with Prime Minister Matteo Renzi pinning his political future on constitutional reform aimed at reducing bureaucracy and legislative gridlock.

Mr Renzi's referendum became an opportunity for voters to pass judgement on him

But the referendum became an opportunity to punish a sitting prime minister, a challenge that was gladly taken up by anti-establishment parties such as the Five Star Movement and the Northern League.

The end result was a heavy defeat and resignation for Mr Renzi.

Professor Jason Brennan of Georgetown University says referendum voters are like fickle sports fans.

"People like referenda where their side wins and hate them when their side loses," he told the BBC. "When their side loses, they say things such as, 'This is why we have representative parliaments.'"

"Better Together" pro-union supporters celebrated after Scotland voted to stay in the UK

Psychologist Amanda Hills, who lectures at King's College London, feels the upswing in referendums is a chance for individuals to engage with politics and shape their own futures.

She says young people tend to be the most proactive if poll results do not go their way: "They get depressed on the day - they comment and are quite distressed. Then they decide to do something about it."

- Published11 November 2016

- Published13 November 2016

- Published31 October 2016

- Published19 October 2016

- Published7 October 2016

- Published25 September 2016