Shoes, furs and hypocrisy: Why we love to hate despots' wives

- Published

Grace Mugabe is so hated that she's probably at greater risk in Zimbabwe than her husband

Marrying a despot guarantees a woman two things: An extravagant lifestyle, and a fragile reputation.

In the eyes of the public, many of these wives earn their condemnation. Aside from their own shady behaviour, they stand by men who have (variously) rejected democracy, ravaged their nations' economies, or killed and exiled their political opponents.

Who can blame a brutalised people for loathing such a figurehead.

But it's fair to ask the question: Are they more reviled because they're female?

'She corrupted him!'

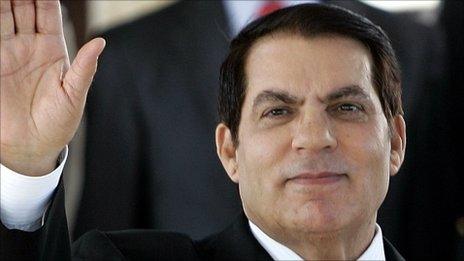

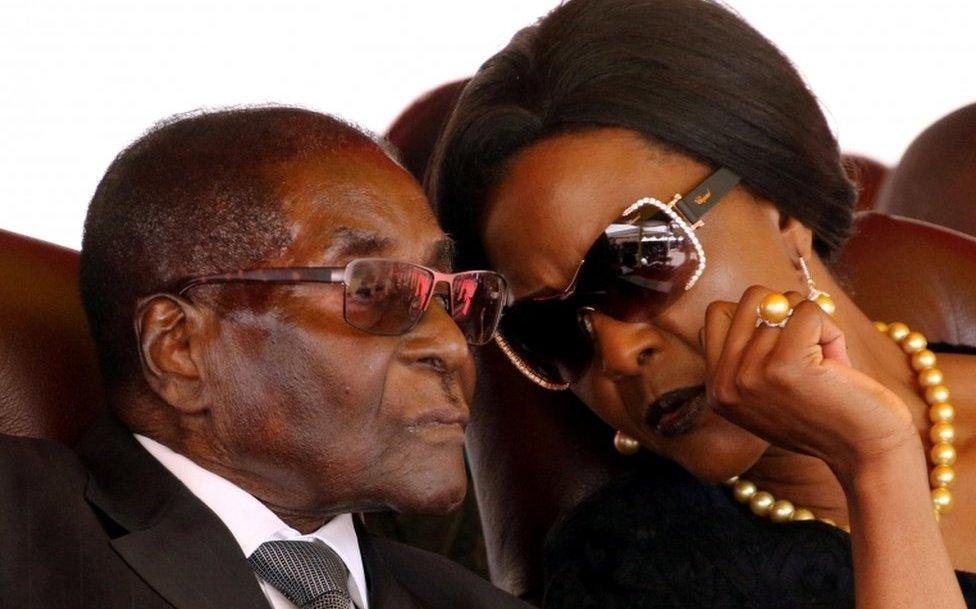

In Zimbabwe, newly ousted first lady Grace Mugabe is probably Africa's most hated woman.

Her husband enjoyed 37 years of authoritarian rule, but was finally undone by her bid to succeed him - which the powerful army could not accept.

Many Zimbabweans have grievances with Robert Mugabe's record, but still respect his part in the country's independence struggle. And so Grace is widely blamed for "corrupting" her husband.

Robert Mugabe's first wife, Sally (left), was seen as a soothing influence, while Grace (right) is seen as inflammatory

Dr Alice Evans, a lecturer in the Department of International Development at King's College London, suggests it's a case of confirmation bias - where people look for evidence to maintain their existing beliefs.

"It's about preserving our ideologies," she says. "So if we valorise Mugabe [for example] as a hero… then all the information that we process has to fit with that view. Even if we see new information about him doing wrong we try to blame it on someone else, to retain that existing ideal."

Grace Mugabe is a divisive person. She had an affair with the president while his popular first wife, Sally Hayfron, was terminally ill. Later, she publicly humiliated senior politicians and was accused of physical assault in both Hong Kong and South Africa.

But she was 15 in 1980, when Zimbabwe won independence and Mr Mugabe became prime minister. And by 1983, when troops allegedly raped and murdered thousands in Matabeleland during his security crackdown, she was only just old enough to vote.

The claims against Mrs Mugabe don't compare to those against Ivory Coast's former first lady, Simone Gbagbo, who was accused of personally arming the death squads that sprang up in 2010 when her husband refused to accept his election defeat.

But they don't need to. Zimbabwe shows a common feature of first lady blaming - it goes to extremes when it's too complex (or too risky) to criticise the man in charge.

Fur coats and designer shoes

Grace Mugabe's nickname, "Gucci Grace", highlights another flashpoint - lavish spending.

This is the archetypal first lady vice, and sadly the tales of excess are often better remembered than the cruelties of the men that funded them.

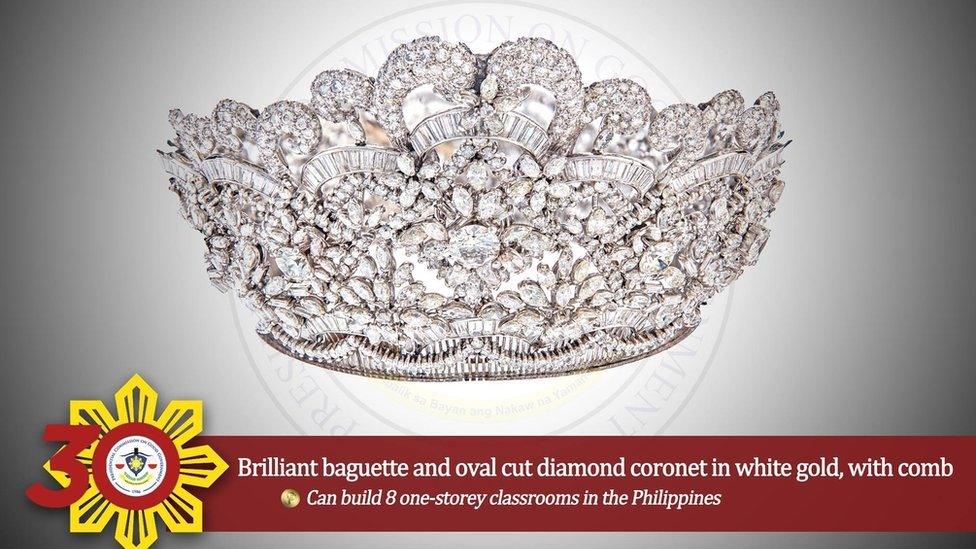

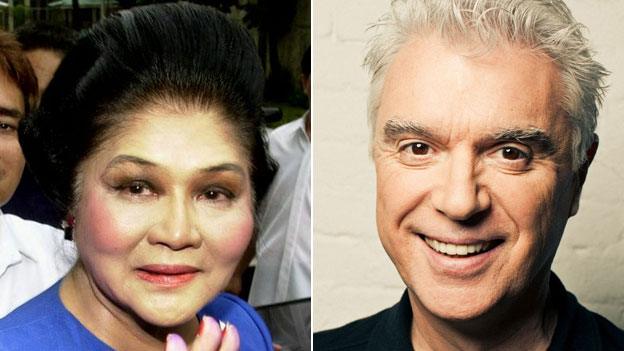

We recall that Imelda Marcos, first lady of the Philippines for more than 20 years, had more than 1,000 pairs of shoes. We may forget exactly why it's gross - that in 1986, when Ferdinand Marcos was ousted by a popular revolt, many Filipinos lived barefoot in abject poverty.

Imelda Marcos, pictured in 2014, is now a congresswoman in the Philippines

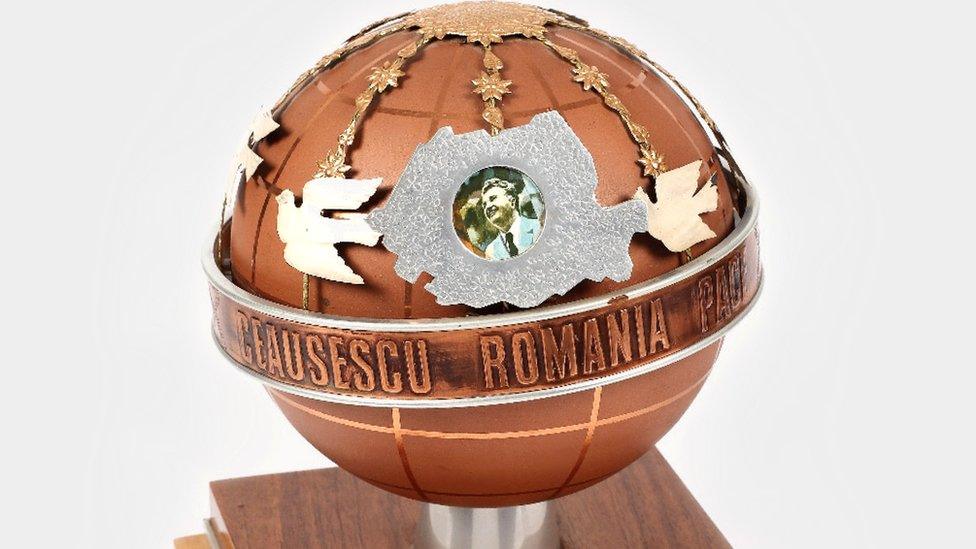

Elena Ceausescu, whose husband Nicolae Ceausescu kept an iron grip on Romania for 24 years from 1965 to 1989, was better known for fur coats than shoes. Fox furs, leopard, zebra pelts, jaguar and tiger... a cornucopia of skins.

A costly example was paraded for the cameras as she and her husband tried to flee the revolution by helicopter in December 1989.

Why do the wifely wardrobes get so much airtime? Well, there's the obvious moral decrepitude of roaming the earth in mink and stilettos while your countryfolk starve. But Dr Evans notes that it's also a very visible form of wrongdoing. More visible, for example, than the closed-door machinations of party officials or secret police.

Cartoon villainesses

Traditionally, unloved political wives get the caricature treatment. Columnists and news channels chalk up comparisons to Lady Macbeth, the original Bad First Lady.

In Kenya, former incumbent Lucy Kibaki was viewed as a one-woman soap opera after 2005, external when she threw furious rages with diplomats and journalists she claimed had not shown her respect.

In one notorious incident, she stormed into a private party thrown by her neighbour, the World Bank's then-country director Makhtar Diop, in a tracksuit at midnight and demanded he turn the music down. President Mwai Kibaki suffered politically as opponents implied he had failed to control his wife - so how could he hope to run a country?

Kenya's former first lady Lucy Kibaki wields a newspaper while speaking to reporters in May 2005

"It fits in with all sorts of easy stereotypes about witches, bad wives, wicked women," says Professor Mary Evans, Emeritus Leverhulme Professor at the Department of Gender Studies, LSE.

"They are cartoon characters in a way. There's some kind of easy template there which it's very easy to write a new name into."

The latest twist on the Lady Macbeth trope is a meme comparing Grace Mugabe to Cersei Lannister, the amoral villainess from the TV show Game of Thrones.

But some Africa watchers argue that by openly confronting anyone who posed a threat to her ambitions, Mrs Mugabe has asserted herself as an individual. If she's judged now, it's not as a mere caricature.

"In Zimbabwe, people judge and have always judged Grace Mugabe, the person," reckons Dr Selina Mudavanhu, a post-doctoral Research Fellow in the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg.

"Social media and the fact that Zimbabweans are in disparate locations in the world has facilitated a much more unfettered critique. Even while she was still first lady and wielded immense power, Zimbabweans circulated jokes ridiculing Grace for her alleged expensive tastes at the expense of the taxpayers."

'Mother of the nation'

So what's at the heart of our hatred for despots' wives? Perhaps it's their frequent hypocrisy - and our sense of betrayal.

"I didn't meddle in politics. I am a woman of the people," declared Leila Ben Ali, the Tunisian ex-first lady sentenced to 35 years for embezzlement, and author of a book called "My Truth".

Mrs Ceausescu was touted as "the best mother of Romania" by her husband's communist regime, but reportedly said of her "children": "The worms never get satisfied, regardless of how much food you give them."

Both Ceausescus were sentenced to death after a summary trial on Christmas Day 1989. Nicolae met the firing squad singing left-wing anthem the Internationale, while Elena screamed obscenities.

Contraception was banned in Romania during the Ceausescu regime, where Elena Ceausescu was touted as "the best mother"

Dr Thekla Morgenroth, a post-doctoral Research Fellow of Social and Organisational Psychology at Exeter University, says it shocks us more when a woman is linked to atrocities.

"It's not just about being gentler - research also shows that we expect women to be more moral, the better gender - the people who are good."

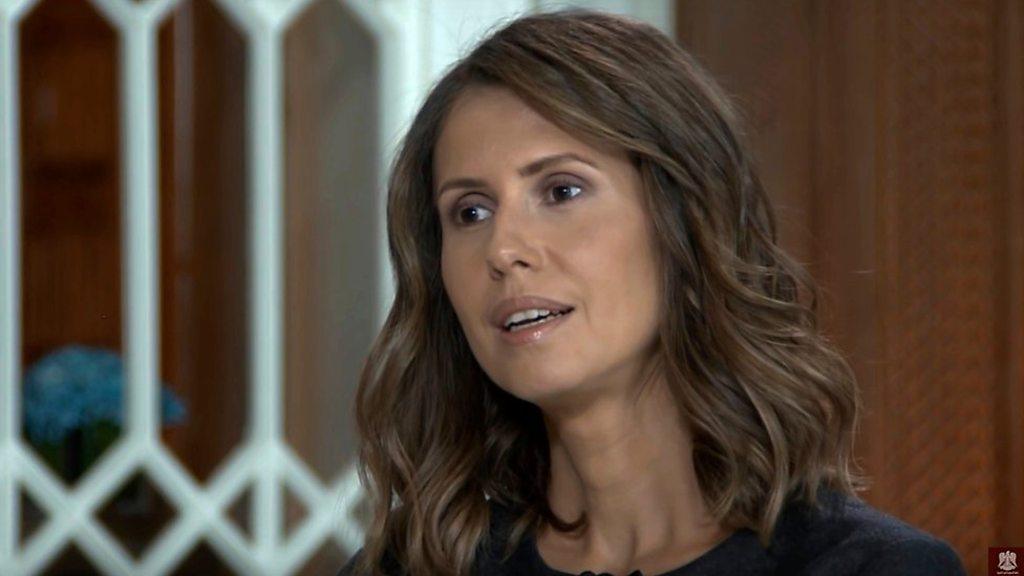

In April 2012, Asma Assad, the British-born wife of Syria's Bashar al-Assad, inspired a YouTube video plea from the wives of the German and British ambassadors to the UN, external, begging her to help stop the bloody repression there.

It contained explicit footage of injured and dying children, and the words, "these children could all be your children".

Activists say at least 400,000 people have been killed in Syria since the country's civil war began in 2011.

A month before the UN wives' appeal, leaked emails had alleged that Mrs Assad was browsing online for $5,000 designer shoes as government forces besieged the city of Homs.

Asma al-Assad: "Western media organisations have chosen to solely focus on the plight of refugees"

In the Catholic religious tradition, Mary the mother of Jesus acts as an intercessor - a mediator between God and humanity. Believers hope her intervention will save their souls.

With the wives of autocrats, we hope for something similar - and when we don't get it, blame the middlewoman instead of the almighty.

- Published21 November 2017

- Published8 April 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published1 October 2014

- Published18 October 2016

- Published18 October 2016

- Published8 February 2012

- Published21 June 2011