'Sun standing still': Why do we celebrate the solstice?

- Published

The winter solstice means summer is on its way, says BBC Weather's John Hammond

All over the world, it is the turning point - when the nights reach their longest in the global north, and the days their longest in the global south.

For the south, it means that the days now begin to slowly shorten and the long journey towards winter has begun. In the north, summer is on the horizon.

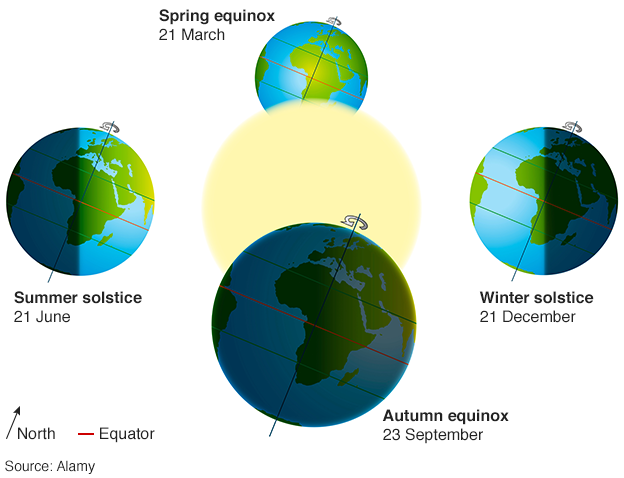

The Earth rotates the Sun on a tilt - at an angle of 23.5 degrees. This tilt gives us our seasons and, twice a year, our solstices.

For the global north, the earth's tilt means that it gets maximum exposure to the sun in June and least in December

Is the solstice at the same instant around the world?

Yes, although obviously the particular time will vary depending on where you are in the world. This year the December solstice is reached at exactly 16:28 GMT and 11:28 Eastern time on Thursday, and 00:28 China Standard Time early on Friday.

That's when the sun reaches its most southerly excursion - directly over the Tropic of Capricorn. In the June solstice, conversely, it reaches its most northerly latitude, over the Tropic of Cancer.

In Fairbanks in Alaska, during the December solstice the sun only just makes it above the horizon, external before the world is dipped back into darkness.

But the solstice doesn't come on the same day each year - it can range from 20-23 December and 20-22 June - because of the discrepancy between our calendar of 365 days a year and the solar year which actually measures 365.2422 days.

What has the solstice meant to people through history?

In English, the world solstice comes from the Latin word solstitium, meaning "sun standing still". It seems to suggest a brief pause as the sun reaches its most extreme point (as experienced on Earth) before the direction of travel is reversed.

The significance of this moment is reflected in monuments and rituals around the world.

The very orientation of the prehistoric Stonehenge standing stones in the UK is along a solstice axis, with a sightline pointing to the December solstice sunset.

Cattle were slaughtered and eaten to reduce the need for feed in the austere winter months; wine and beer were fermented in time for the festivities.

Stonehenge's very construction appears to have been based on the solstices

Partying and feasting has a long association with the solstice.

In ancient Rome, Saturnalia was a week-long festival of light running up to the winter solstice, where the social order was turned on its head - masters served their slaves, gambling was permitted and debauchery reigned.

In Scandinavia, the pre-Christian Feast of Juul commemorated the solstice. Fires were lit to symbolise the life-giving properties of the Sun. A Juul (or Yule) log or tree was burned in the hearth.

And in fact, the tradition of the Christmas tree may have its roots in such pre-Christian traditions associated with the solstice.

Nowadays, festivals of the solstice continue.

In Newgrange, Ireland, the sunlight pierces through a 5,200-year-old chamber on solstice morning. This year, the authorities livestreamed the light.

There are rituals and celebrations from Norway to China, India to Belarus.

Bolivia's indigenous Aymara people mark the December solstice near Titicaca lake

- Published21 December 2014