How fake news plagued 2017

- Published

Texas shooting: How to spot a hoax

In August a devastating hurricane hit the Americas - it was so powerful it broke records, becoming the first category-six storm ever.

"Irma, strongest hurricane, recorded category six," warned Alex Jones of American website InfoWars, broadcast to more than 750,000 followers on Facebook.

Except it wasn't. Category six hurricanes don't exist. It was fake news.

Maybe you saw the story. It was shared more than two million times from numerous Facebook pages. Someone you know probably believed it - a friend, a colleague, maybe your grandmother.

It wasn't the only time fake news followed the biggest news stories of 2017.

Terror Attacks

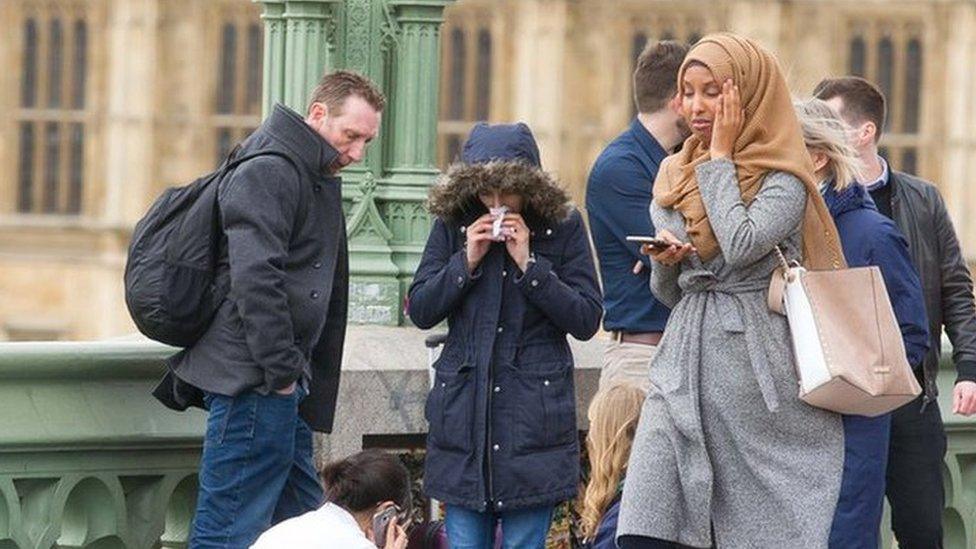

In the hours after six people were killed and 50 injured in a terror attack in London, UK, on 22 March, a photograph was widely circulated of a woman wearing a hijab and talking on the phone on Westminster Bridge, the site of the attack.

Thousands shared the picture claiming the woman, as a Muslim, was indifferent to the suffering of victims around her. #BanIslam was one hashtag circulating with the image.

The woman in the picture released a statement, external and spoke of being "devastated by witnessing the aftermath of a shocking and numbing terror attack," after the negative attention she received.

The account, @SouthLoneStar, which first tweeted the image, was suspended by Twitter in November after being identified as a Russian bot.

In May, less than two hours after a bomb at the Manchester Arena killed 22 people, pictures circulated of people under the hashtag #MissingInManchester.

One picture turned out to be of a boy who modelled for a fashion line several years previously.

Another tweet, shared more than 35,000 times, was from a user claiming his brother and sister were missing. But the image shared was taken before the attack and a Twitter user said it was actually a photo of a younger version of himself.

Another photo used in one montage was of Jayden Parkinson, murdered in 2013. "It is horrible to see her photo being used in this way," Samantha Shrewsbury, her mother, told the BBC.

What is fake news?

Completely false information, photos or videos purposefully created and spread to confuse or misinform

Information, photos or videos manipulated to deceive - or old photographs shared as new

Satire or parody which means no harm but can fool people

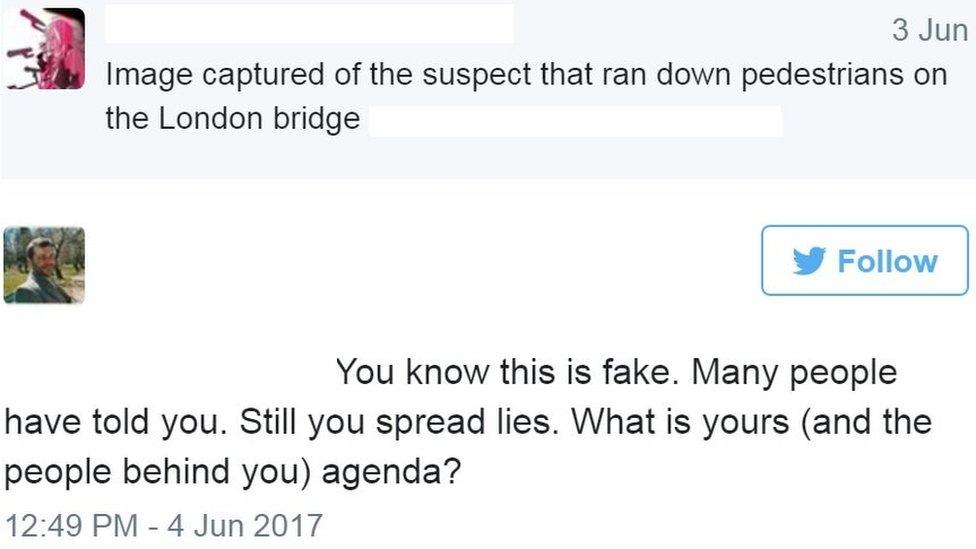

After the London Bridge attack on 3 June, in which attackers drove a van into pedestrians and stabbed several people, killing eight, online trolls quickly shared a photo claiming to show the suspect, but the image was of US comedian Sam Hyde.

The same pictures of Hyde, external were shared after the attack on Finsbury Park mosque in London on 19 June and again after the killing of 58 people in a mass shooting in Las Vegas in October.

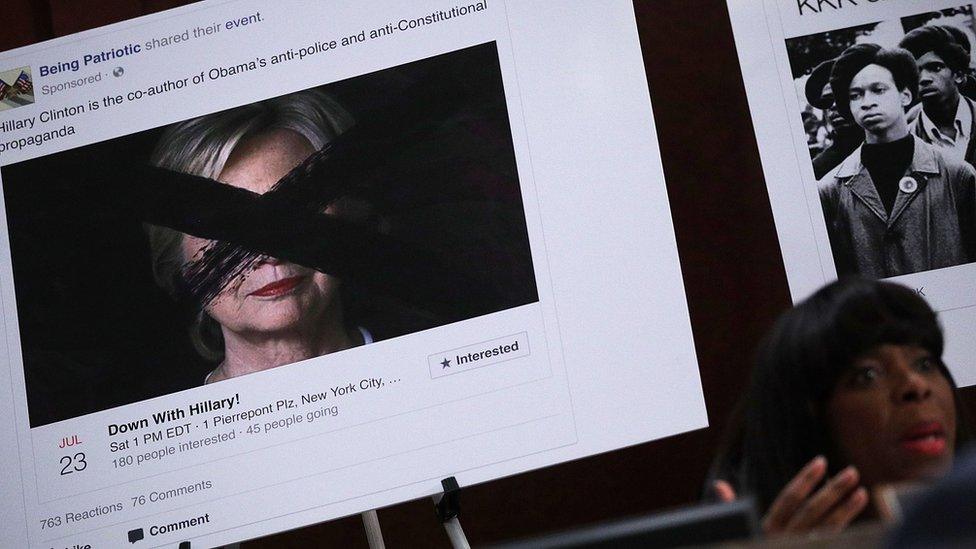

Google also promoted fake articles about the shooter, external from right-wing blogs which claimed the shooter was an anti-Trump liberal.

Grenfell Tower

In June a devastating fire ripped through Grenfell Tower in London, but the scale and intensity of the fire meant information was scarce in the first hours and days - it wasn't until November the final death toll of 71 was known.

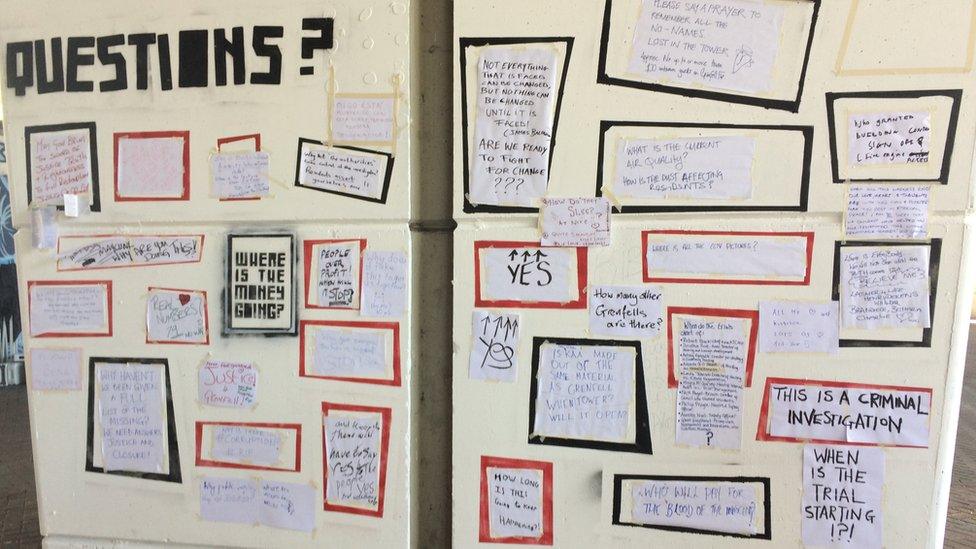

Rumours and misinformation filled the gap. For those who experienced the trauma of a monstrous fire, trusting mainstream media and officials was difficult.

A wall of posters has appeared near the tower

The biggest topic of conflicting information was the death toll. Facebook, Telegram and WhatsApp groups were set up to share information about the missing and deceased. Some shared rumours that the death toll was in the hundreds, not believing the official figures released soon after the fire.

A video shared on Facebook by prominent social media personality Majid Freeman, external was seen 6.6 million times it included claims 42 bodies were found in one room of the building. The claim was never confirmed by authorities. Those commenting below the video said they believed it was certain the death toll was in the hundreds.

A clickbait website reported that a baby was rescued from the building 12 days after the fire started - only for the story to be debunked hours later.

While the fire was still raging, news outlets, including the BBC, reported a baby was saved after being thrown from the 10th floor, but nobody ever came forward to say their infant was caught or that they caught a baby. In October a BBC investigation suggested that the dramatic rescue probably never happened.

Hurricanes and earthquakes

When Storm Harvey displaced thousands in Texas, US, in August, a Canadian imam had to point out he had never been to the state after he was accused of closing his mosque's doors to Christian victims in a fake story been shared more than 126,000 times.

Meteorologists and social media users issued warnings about fake Hurricane Irma news

During Hurricane Irma the White House fell for a fake video claiming to be Miami Airport, a doctored forecast was shared almost 40,000 times, and a video of the wrong storm was viewed almost 28 millions times on Facebook.

Inaccurate advice that valuables be stored in dishwashers was also widely shared.

You might also like

Then in September a girl called Frida Sofia caught the attention of much of Mexico after she was trapped in a deadly earthquake. But it seems Frida never existed and instead was the fictional product of collective hope in the face of disaster.

And after a deadly earthquake struck the Iran-Iraq border in November, a video of a young boy securing food for his friend was widely shared, but the video was not filmed in the aftermath of the earthquake.

While 2018 will probably see more fake news circulating around the big stories, there are efforts to try and limit its impact. Facebook is attempting to alert users to potential misinformation by displaying fact-checked articles next to disputed stories. And Twitter expanded its rules in early December as to what is classed as hateful or harmful behaviour on the platform.

However, alerting users to fake content is not easy, with Twitter banning a crowd-sourced bot designed to warn people about fake accounts. The bot was suspended in December following a large number of "spam complaints".

- Published6 December 2017

- Published14 November 2017

- Published21 December 2017

- Published22 September 2017