Trade wars, Trump tariffs and protectionism explained

- Published

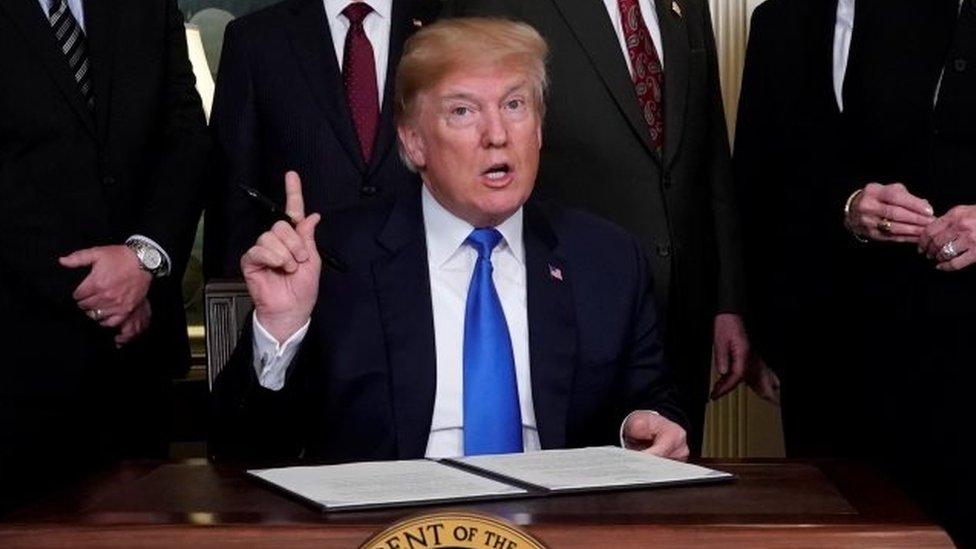

President Trump has imposed tariffs on a range of Chinese goods

US President Donald Trump has shaken the foundations of global trade, slapping steep tariffs on billions of dollars' worth of goods from the EU, Canada, Mexico and China.

All these countries are responding in kind, retaliating with levies on thousands of US products.

This puts the world's largest economies at each other's throats.

But what is a trade war? How does protectionism work? And how will it all affect you?

What is a trade war?

It's what it sounds like - a trade war is when countries try to attack each other's trade with taxes and quotas.

One country will raise tariffs, a type of tax, causing the other to respond, in a tit-for-tat escalation.

This can hurt other nations' economies and lead to rising political tensions between them.

US President Donald Trump reckons trade wars are "good" and easy. He's not afraid to raise tariffs.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But what is a tariff?

It's a tax on a product made abroad.

In theory, taxing items coming into the country means people are less likely to buy them as they become more expensive.

The intention is that they buy cheaper local products instead - boosting your country's economy.

Why is Trump doing this?

The president has placed tariffs on billions of dollars' worth of goods from around the world, in particular China.

He's imposed a 10% levy on $200bn (£150bn) worth of Chinese products so far. In May, he announced plans to impose a 25% tariff on $325bn of other Chinese goods, external.

Mr Trump said the $100bn gained from the tariffs will be used to buy US agricultural products, which will then be sent to "poor and starving countries" for "humanitarian assistance".

He also wants to cut the trade deficit with China - a country he has accused of unfair trade practices since before he became president.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Trump made a big point on the campaign trail about cutting the country's trade deficits.

He's convinced it hurts US manufacturing, and has said time and time again on the stump and on Twitter that the US must do more to tackle them, external.

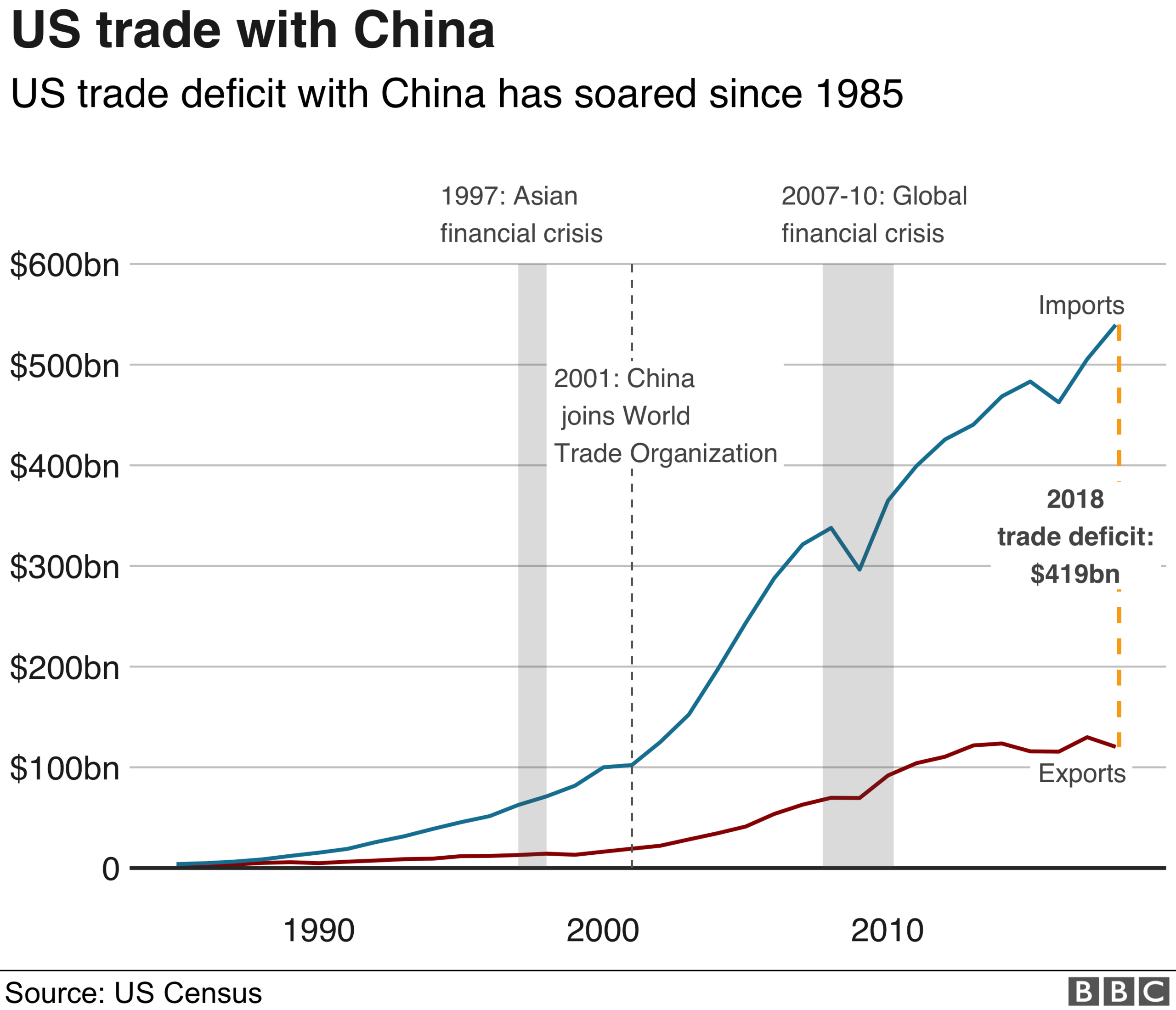

What's a trade deficit?

It's a term meaning the difference between how much your country buys from another country, compared with how much you sell to that country.

And the US has a massive trade deficit with China. Last year, it widened by $43.6bn to $419.2bn.

He wants to cut back this trade deficit, and he intends to use tariffs to do it.

But while the president hates them, trade deficits are not necessarily a bad thing.

Many wealthier countries have in recent decades shifted from manufacturing economies to service economies - focusing on areas like banking, travel and tourism.

Services contribute to the majority of the US economy's net income. China, in contrast, doesn't export nearly as many services as it does manufactured goods.

So the president's obsession with trade deficits is not always popular, with critics damning the administration's moves as protectionism.

Trump constantly worries about the trade deficit - should we?

What's protectionism?

Protectionism is trying to use restrictions such as tariffs to boost your country's industry, and shield it from foreign competition.

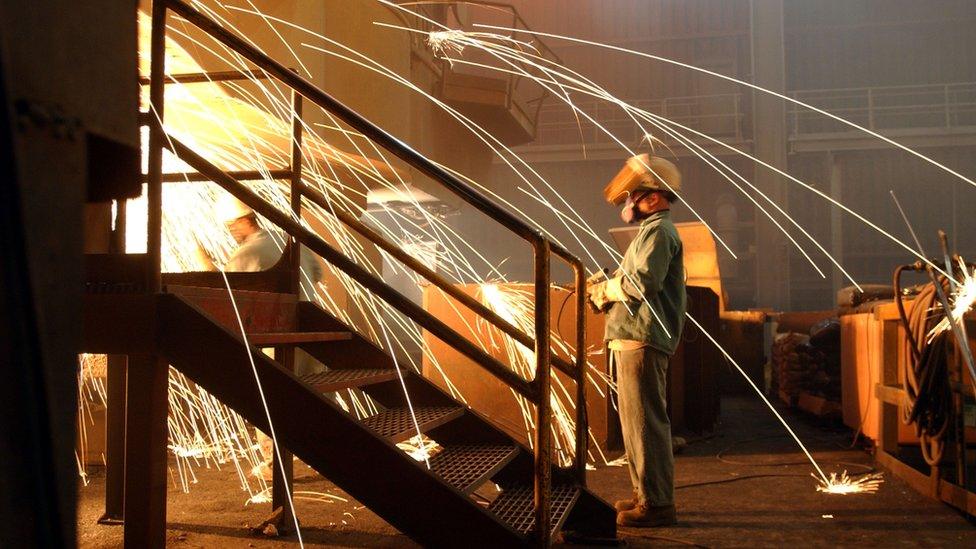

Take Mr Trump's steel and aluminium tariffs.

In May 2018, the president announced a 25% tariff on all steel imports, and 10% on aluminium.

The Trump administration claims the US relies too much on other countries for its metals, and that it couldn't make enough weapons or vehicles using its own industry if a war broke out.

Critics point out the US gets most of its steel from Canada and the EU - staunch US allies.

In theory, taxing foreign steel and aluminium will mean US companies will buy local steel instead.

The thinking is that will boost the US steel and aluminium industries, as more companies will want to buy their goods.

Steel and aluminium prices will go up in the US because there will be less of these goods coming in from abroad - so the greater demand for local steel will push up the price, lifting profits for steel makers.

The number of people employed in the US steel industry fell by almost 50,000 between 2000 and 2016

But does it work?

Sort of.

US steel makers could get a boost - demand will drive new hires and bigger profits.

But the US companies that need raw materials, like car and aeroplane makers, will see their costs rise.

That means they might have to put up the prices on their finished products. That would hurt consumers.

So car prices could go up in the US. As could prices for gadgets, plane tickets and even beer - the price of making a can could rise.

Making beer cans could become more pricey - and that cost could be pushed onto consumers

How could tariffs affect me?

They could affect people around the world - especially since China has retaliated.

The world's second-largest economy has taxed US agricultural and industrial products, from soybeans, pork and cotton to aeroplanes, cars and steel pipes. It has also pledged to take "necessary countermeasures" over Trump's latest proposed tariffs.

In theory, China could also tax US tech companies like Apple. That would hit the tech giant, and it could be forced to raise its prices to compensate.

A global trade war could hurt consumers around the world by making it harder for all companies to operate, forcing them to push higher prices onto their customers.

Is free trade better then?

Depends who you ask.

Free trade is the opposite of protectionism - it means as few tariffs as possible, giving people the freedom to buy cheaper or better-made products from anywhere in the world.

This is great for companies trying to cut costs, and that's helped drive prices down and boost the world economy.

Free trade has led to a vast expansion of shipping and transfer of goods around the world

Cars, smart phones, food, flowers - free trade has brought affordable products from around the world to your home.

But at the same time, that means companies are less likely to buy local products. Why buy domestic when you can get more, cheaper, from a different country?

This means the loss of jobs in wealthier countries, and uneven growth - while free trade has made some people richer, it's made others poorer.

How is it all going to end?

No idea.

Historians have pointed out that tariffs often lead to higher costs for the consumer, while economists across the board are against the plans.

The Republican Party is also overwhelmingly against Mr Trump on tariffs - they're big supporters of free trade.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Trump's decision to take on China could lead to adverse effects for consumers in the US and in China, but also worldwide.

An economic showdown between the world's biggest economies doesn't look good for anyone.

- Published15 June 2018

- Published23 March 2018

- Published22 March 2018

- Published1 March 2018

- Published8 March 2018