Is the Amazon facing new dangers?

- Published

Environmental groups and politicians have raised the alarm about the policies of Brazil's new president, Jair Bolsonaro.

The outgoing environment minister Edson Duarte said during the campaign that victory for Mr Bolsonaro would have an instant impact.

"The increase of deforestation will be immediate," he told a Brazilian newspaper.

"I am afraid of a gold rush to see who arrives first."

Critics justify their fears by pointing to Mr Bolsonaro's comments during the campaign. He pledged to limit fines for damaging forestry and to weaken the influence of the environmental agency.

An aide of the president-elect has announced the new administration will merge the environment and agricultural ministries. A former environment minister said the move will "bring serious damage to Brazil."

However in an interview with the BBC, the incoming vice-president Hamilton Mourao said the Amazon rainforest would be cared for and laws will be applied.

"We've been protecting our rainforest. I believe no country has done this like we have. Our environmental laws are very tough."

Brazilians are waiting to see how the new administration might affect the Amazon rainforest.

So how successful has Brazil been in protecting one of the world's most biodiverse regions, and what impact might these new policies have?

The Amazon is the largest tropical rainforest in the world, and 60% of it is within Brazil's borders.

It is home to thousands of plant and wildlife species, as well as the indigenous communities who live there.

It also plays a critical role in absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, a vital contribution to maintaining the balance of the air we breathe and in limiting global warming.

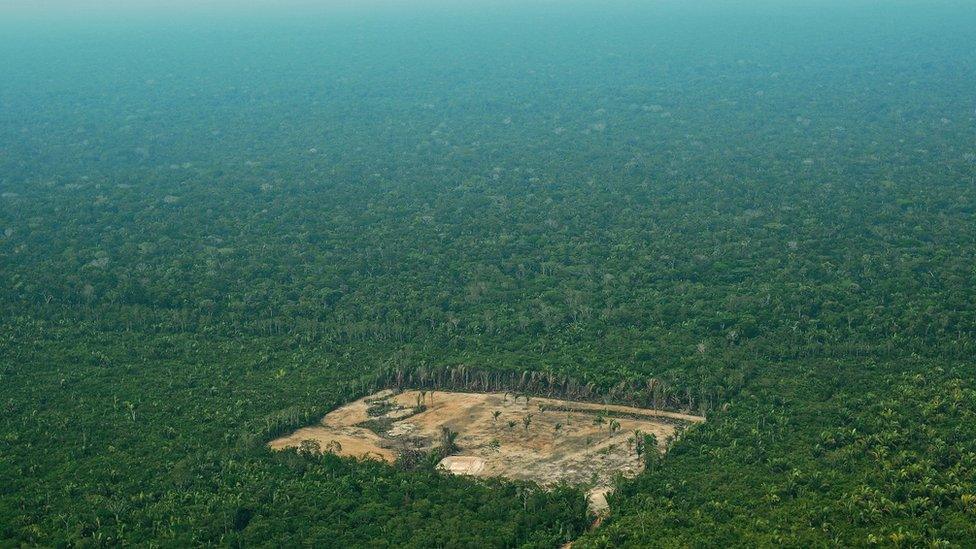

Cattle farming and soy plantations are the dominant drivers of deforestation, according to the Global Forest Atlas, external.

Over the past half century, the forest has been cleared at an alarming rate. It's estimated that since 1970, around 20% has been lost.

However, after reaching a peak in 2004 - when an area nearly the size of Belgium was being lost every year - the rate of deforestation has shown a marked decrease.

A Brazilian government project using satellite images to monitor primary rainforest estimates that by last year, deforestation had fallen by 75% from its 2004 peak. It has increased again since 2012 and persists due to illegal deforestation and logging.

This slowdown in deforestation has been attributed to government policies including fines for breaking land use regulations, and sanctioning of the worst offending municipalities.

International campaigns to stop the trade of soy and beef farmed on deforested parts of the Amazon have also been seen as having a significant impact.

The environmental group Greenpeace has highlighted vast patches of rainforest, external destroyed to meet the global demand for soybean - used primarily as animal feed.

In 2006 Brazilian and global companies signed a moratorium ensuring that buyers would not purchase soybean grown on deforested land.

However, despite this progress, there may be signs that smaller-scale deforestation is on the rise.

A monitoring project run by the University of Maryland measures primary rainforest and forest destroyed by fire, secondary forest (areas that have already been disturbed) and much smaller patches of land than those tracked by the Brazilian government.

The project data suggests that deforestation is occurring at a much greater rate, external than that recorded by the Brazilian authorities. This discrepancy might reflect attempts by landowners to evade monitoring of deforestation by clearing land below the reporting threshold, according to a study in Scientific Reports, external.

"If left undetected and unmonitored, you'll have a scenario of the Amazon 'dying by a thousand cuts,'" says Michelle Kalamandeen, a conservation biologist at Leeds University, who worked on the study.

Away from the Amazon rainforest, the Cerrado savanna is the heart of agricultural production in Brazil.

It is a new battleground for conservationists in Brazil, who feel the Cerrado has slipped under the radar and its weaker regulations exploited.

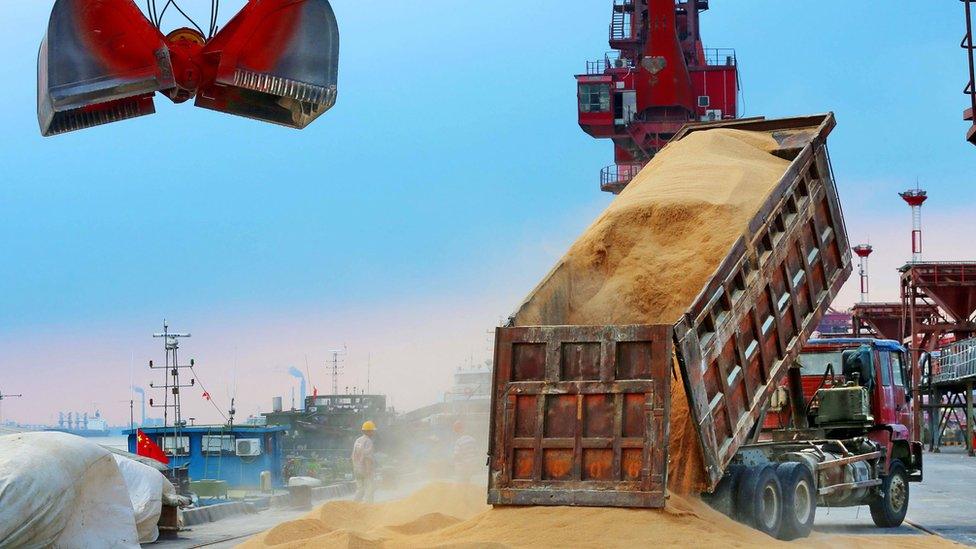

China is a major importer of soybeans from Brazil

The vast area has lost much of its natural vegetation to agriculture and the rate of deforestation is exceeding the Amazon, according to an FT report, external.

Recent pressure from campaign groups has put the Cerrado in the spotlight. Dozens of companies (including Marks & Spencer, Tesco and McDonald's) have signed the Cerrado Manifesto, launched last year, to work with "local and international stakeholders to eliminate deforestation and the loss of vegetation in the Cerrado, external".

But it's not necessarily easy to control global market forces.

Brazil is the world's leading producer of soybeans, most of it grown in the Cerrado.

Demand for the bean is unlikely to abate, especially from China, which could become more reliant on Brazil after the US increased tariffs on its soybean exports.

It's also difficult to predict what impact President Bolsonaro's government will have on the levels of deforestation. Although he has promised on the campaign trail to reduce regulations preventing forest clearance, he has yet to clarify these policies.

His avowed disdain for the Paris agreement on limiting climate change may also yet turn out to be little more than campaign rhetoric.

- Published29 October 2018

- Published24 August 2017