Remembering Brazil's decades of military repression

- Published

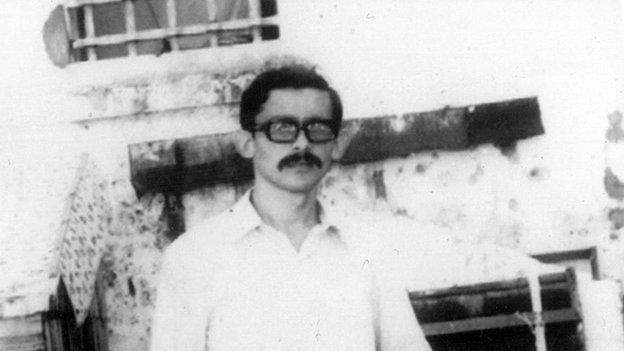

Pablo Uchoa's father Inocencio was detained in 1968 and held in the infamous "dungeons" of the regime

On 31 March, Brazil marks the 50th anniversary of the coup which ushered in two decades of military rule. In the repression which followed, almost 500 people were disappeared or killed, and many more detained and tortured. BBC Brasil's Pablo Uchoa recalls the story of one of the detainees, his father Inocencio.

Growing up, I never saw my father as a superhero. But I knew he was a strong man.

Word had it that he had been beaten so aggressively by the military regime that his aggressors once broke a baton on his body.

I was brought up in a politicised, but otherwise ordinary, middle-class family in north-eastern Brazil. The brutal details of what happened in the torture chambers of my country were never mentioned during family events.

Revolution on the mind

My father, Inocencio, was one of 14 surviving siblings born into a humble family. Noticing his love of and aptitude for studying his parents sent him to a religious school, as they had the best reputation.

But by 1965, when he was admitted to university in Fortaleza, his interest and passion had shifted away from his studies and towards politics.

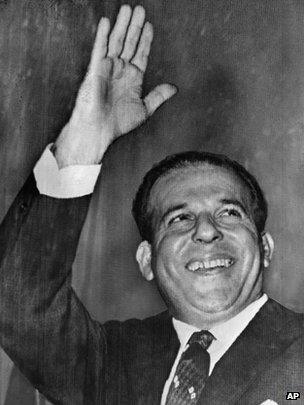

A year earlier, he had watched as army tanks occupied the streets of Brazilian cities and deposed the leftist government of President Joao Goulart - an event which had left a lasting impression on him.

"We entered university as students, but over the course of the years we were hardly concerned with finishing our studies anymore," my father recounted in a recent documentary about political prisoners, A Mesa Vermelha (The Red Table).

"I was not (interested) in the slightest, I wanted to make revolution."

Torturous nights

Upon seizing power in 1964, the military regime - fully supported by the US - promised swift action to bring "order" back to a country it perceived as slipping towards communism.

Joao Goulart was deposed in a coup in 1964

But four years on, not only was the regime no closer to handing power over to civilians, it was ready to ramp up repression.

In March 1968, 18-year-old Edson Luis, a high-school student, was shot at point-blank range by the police during a demonstration in Rio de Janeiro.

In October, hundreds of students were arrested during a meeting in the town of Ibiuna. About 70 student leaders were indicted.

Among them was the vocal president of the students' union at the Federal University in north-eastern Ceara state: my father.

Before the year had ended, the military government had issued Institutional Act 5, which disbanded Congress, suspended habeas corpus for political crimes, and stepped up censorship.

It is this period of my father's life which remained murky to me for many years.

Painful memories

It was not until recently that I first heard his account of the nights he was left standing handcuffed to his cell bars, purposely being deprived of sleep.

Or the night when he and a few other comrades were taken on a long truck ride down to a deserted beach.

There, they were lined up and subjected to a mock execution, his life flashing before his mind's eye as armed men cocked their weapons, aimed... and were told to stop.

Opponents of the regime were subjected to harsh physical ordeals.

One of the infamous torture methods consisted of leaving prisoners hanging upside down from a pole for hours, heels and wrists tied together in a position known as the "parrot's perch".

Many prisoners were also subjected to electrical shocks to their finger tips, genitals, and wherever else the sadistic imagination of their torturers would choose.

My father, conscious of the fact that hundreds of people who were tortured did not survive, deliberately underplays the brutal beatings he received.

He spent a year in detention, and was lucky to be released for a few months before his sentence was extended by another year.

Clandestine life

During his release, he fled from the city of Fortaleza to Rio de Janeiro, where he joined my mother, Angela.

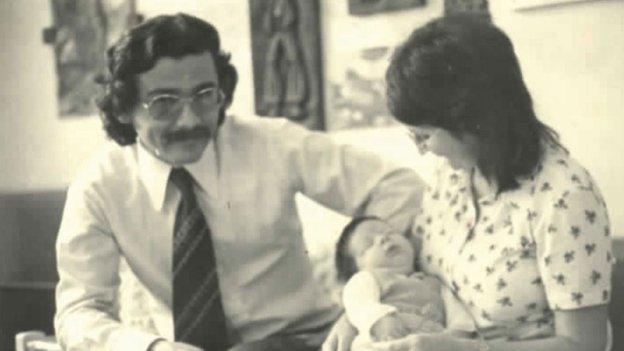

Inocencio Uchoa and his wife Angela during their honeymoon, before his sentence was extended

Pablo Uchoa's older brother Marcelo was born while his parents were living in hiding

There they lived in hiding for almost a decade.

My brother and I were born during this clandestine time. My brother was named Marcelo, which was also my father's alias while in hiding.

In 1979, Brazil's military government passed an amnesty law which made it possible for my family to return to Fortaleza.

But the same amnesty law also shielded those who had committed human rights violations from prosecution.

Both my parents were highly active in the campaign demanding citizens be able to cast a direct vote in presidential elections.

Hope amidst repression

They taught us to pin our hopes to the political struggle.

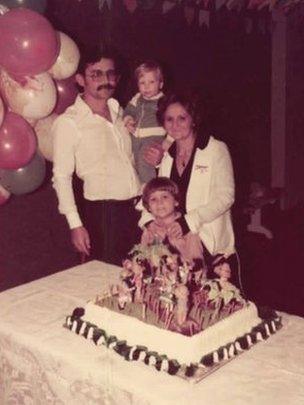

Pablo Uchoa (in his father's arms) on his birthday

Like many of his generation, my father is still reluctant to describe in detail what happened in the regime's dark chambers.

It is painful, he tells me, and "society needs some time to digest it".

After the return to democracy in 1985, "our logic was to help strengthen the unions, civil organisations, fight for the Constituent Assembly, for the vote," he explains.

"There was a sequence of events that didn't allow us to talk about torture too much," he adds.

There were practical reasons, too.

A recent search through declassified documents held in the National Archives shows that the secret services continued to keep an eye on him at least until 1989 - a full decade after the amnesty law was passed.

It is only now that my father feels the time has come to open up. He has requested to be granted the status of former political prisoner, not to claim financial compensation but to gain the recognition he is owed.

He has also been sharing his experiences with a recently created truth commission. Unlike some similar commissions elsewhere in the world, Brazil's truth commission does not have the power to seek prosecutions.

The amnesty law, passed in 1979, remains in place, meaning that neither military officials accused of torture nor left-wing guerrillas accused of violence will face trial.

Looking back at the decades which have passed since the coup, my father says that "everything has its moment".

"In 1984, we were still coming out of the dictatorship. Ten years later, we didn't want to talk about it. We talked about it a little in 2004."

"Now, Brazil is facing its truths for the first time."

- Published14 November 2013

- Published16 May 2012

- Published16 May 2012