Why so many people believe conspiracy theories

- Published

Did Hillary Clinton mastermind a global child-trafficking ring from a Washington pizzeria? No.

Did George W Bush orchestrate a plot to bring down the Twin Towers and kill thousands of people in 2001? Also no.

So, why do some people believe they did? And what do conspiracy theories tell us about the way we see the world?

Conspiracy theories are far from a new phenomenon. They have been a constant hum in the background for at least the past 100 years, says Prof Joe Uscinski, author of American Conspiracy Theories.

They are also more widespread than you might think.

"Everybody believes in at least one and probably a few," he says. "And the reason is simple: there is an infinite number of conspiracy theories out there. If we were to poll on all of them, everybody is going to check a few boxes."

Comet Ping Pong Pizzeria became the subject of an online conspiracy theory about child trafficking

This finding isn't peculiar to the US. In 2015, University of Cambridge research found most Britons ticked a box when presented with a list of just five theories. These ranged from the existence of a secret group controlling world events, to contact with aliens.

This suggests that, contrary to popular belief, the typical conspiracy theorist is not a middle-aged man living in his mother's basement sporting a tinfoil hat.

"When you actually look at the demographic data, belief in conspiracies cuts across social class, it cuts across gender and it cuts across age," Prof Chris French, a psychologist at Goldsmith's, University of London, says.

Equally, whether you're on the left or the right, you're just as likely to see plots against you.

"The two sides are equal in terms of conspiracy thinking," Prof Uscinski says, of research in the US, external.

"People who believe that Bush blew up the Twin Towers were mostly Democrats, people who thought that Obama faked his own birth certificate were mostly Republicans - but it was about even numbers within each party."

Conspiracy theories

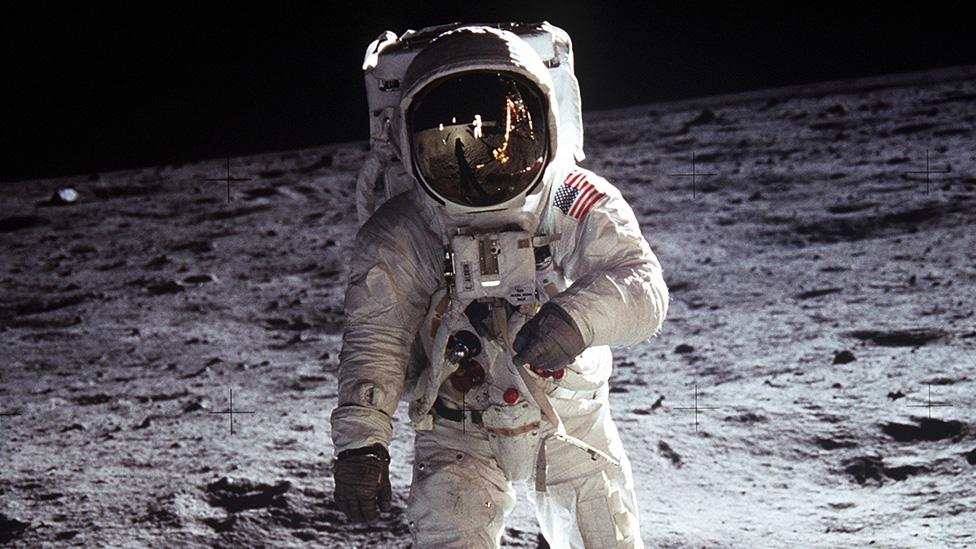

The theory that the Moon landings were faked has prompted detailed explanations rebutting the claims, external

Claims that Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hess was replaced by a double in jail were debunked by DNA provided by a distant male relative

Musicians Beyoncé, Paul McCartney and Avril Lavigne have all faced rumours that they were replaced by clones

Some versions of claims that a shadowy group called the Illuminati control the world suggest celebrities and politicians are members

To understand why we are so drawn to the notion of shadowy forces controlling political events, we need to think about the psychology behind conspiracy theories.

"We are very good at recognising patterns and regularities. But sometimes we overplay that - we think we see meaning and significance when it isn't really there," Prof French says.

"We also assume that when something happens, it happens because someone or something made it happen for a reason."

Essentially, we see some coincidences around big events and we then make up a story out of them.

That story becomes a conspiracy theory because it contains "goodies" and "baddies" - the latter being responsible for all the things we don't like.

Blaming politicians

In many ways, this is just like everyday politics.

We often blame politicians for bad events, even when those events are beyond their control, says Prof Larry Bartels, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University.

"People will blindly reward or punish the government for good or bad times without really having any clear understanding of whether or how the government's policies have contributed to those outcomes," he says.

Barack Obama released his birth certificate in 2011 in response to persistent rumours he had been born outside the US

This is even true when things that seem very unrelated to government go wrong.

"One instance that we looked at in some detail was a series of shark attacks off the coast of New Jersey in 1916," Prof Bartels says, external.

"This was the basis, much later, for the movie Jaws. We found that there was a pretty significant downturn in support for President [Woodrow] Wilson in the areas that had been most heavily affected by the shark attacks."

The "us" and "them" role of conspiracy theories can be found in more mainstream political groups as well.

In the UK, the EU referendum has created a group of Remainers and a similarly sized group of Leavers.

"People feel they belong to their group but it also means that people feel a certain sense of antagonism towards people in the other group," Prof Sara Hobolt, of the London School of Economics, says.

Remainers and Leavers sometimes interpret the world differently. For example, confronted with identical economic facts, external, Remainers are more likely to say the economy is performing poorly and Leavers to say it is performing well.

Conspiracy theories are just another part of this.

"Leavers, who, in the run-up to the referendum, thought they were going to be on the losing side, were more likely to think that the referendum might be rigged," Prof Hobolt says.

"And then that really shifted after the referendum results came out, because at that point the Remainers were on the losing side."

No solutions

It may not be terribly cheering to learn that conspiracy theories are so embedded in political thinking. But it should not be surprising.

"It's often the case that we're constructing our beliefs in ways that support what we want to be true," Prof Bartels says.

And having more information is little help.

"The people who are most subject to these biases are the people who are paying the most attention," he says.

For many, there is little reason to get political facts right, since your individual vote won't affect government policy.

"There is no cost for me to be wrong about my political views," Prof Bartels says.

"If it makes me feel good to think that Woodrow Wilson should have been able to prevent the shark attacks, then the psychological pay-off from holding those views is likely to be much greater than any penalty that I might suffer if the views are wrong."

In the end, we want to feel comfortable, not be right.

It is why particular conspiracy theories come and go, but also why conspiracy will always be part of the stories we tell about political events.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

James Tilley is professor of politics, external and fellow of Jesus College, University of Oxford.

His programme Conspiracy Politics was broadcast on BBC Radio 4's Analysis on 11 February and can be listened to here.

Edited by Duncan Walker