The grief that comes from lost buildings

- Published

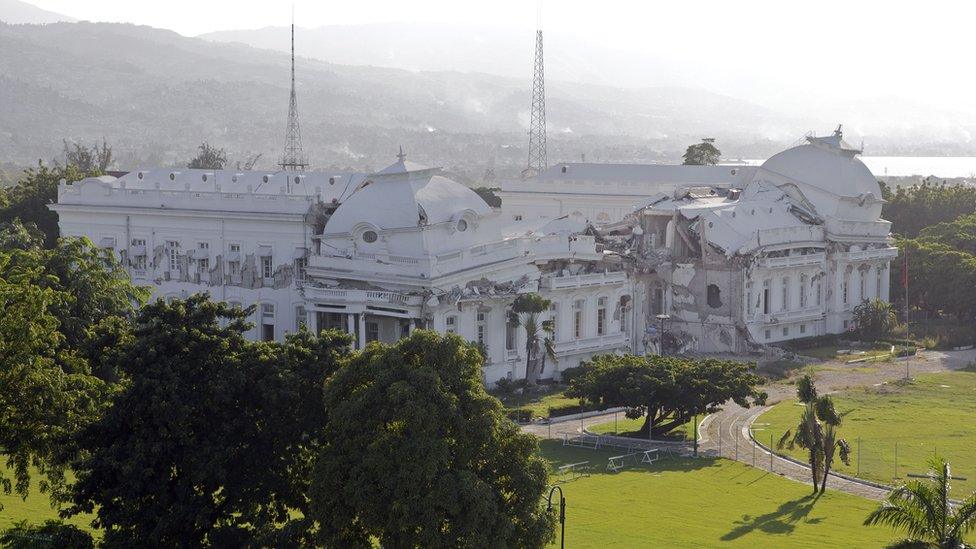

The Presidential Palace in Haiti was wrecked by an earthquake in 2010

Why do people mourn the loss of buildings?

Across the world, destruction of cultural attractions causes a specific sort of communal grief.

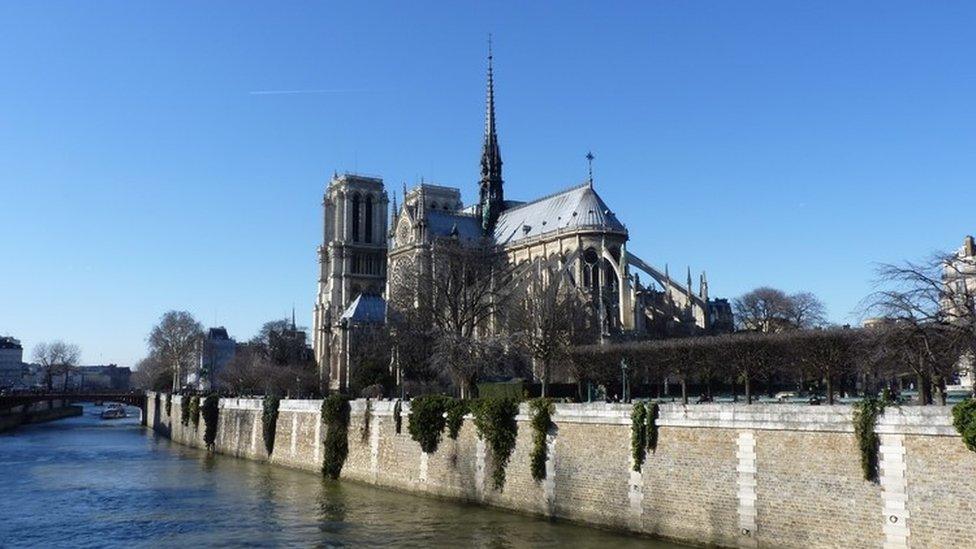

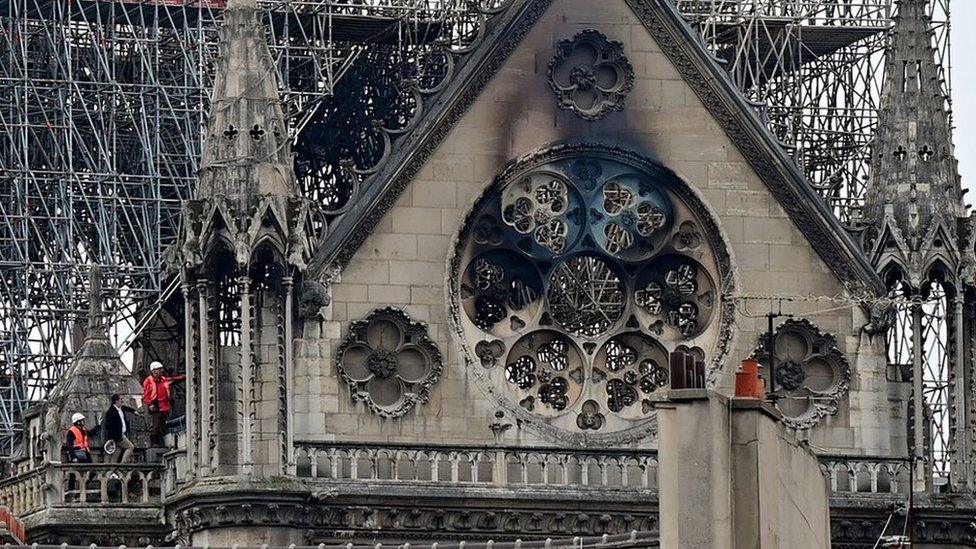

Parisians have spoken about how the devastating fire at Notre-Dame cathedral has made them think about identity, memory and shared culture.

Here, people from other countries talk about their experiences seeing important sights destroyed - some under very different circumstances.

Brazil: The National Museum

The 200-year-old former royal palace that housed Brazil's national museum in Rio de Janeiro was gutted by fire in September last year. Flames tore through rooms containing some 20m artifacts; very little survived.

Bruna Arakaki, a graphic designer from Rio, watched the blaze from her apartment. She says seeing the Notre-Dame fire in the news brought that sadness back and evoked a sense of solidarity with Parisians.

"It felt like part of who we are and our history burnt alongside the museum," she says. "People were very fond of it. It was in a poorer part of the city and was one of few museums in that area. For many generations, it was the first museum they visited."

Many people have blamed the authorities, saying a lack of funding had left it vulnerable. "Watching it burn, there was a feeling of impotence and revolt," says Ms Arakaki. "It was so imposing and had been there so long, no-one expected that one day it would just end."

Drone footage shows the National Museum totally gutted.

Filmmaking student João Gabriel Barreto was an intern at the museum in 2014. He is still in a WhatsApp group with his old colleagues, and they shared tearful, panic-stricken messages on the night of the fire.

"We didn't know what to feel or think about it. It was so messed up," says Mr Barreto. "It felt like a huge part of our bonding was being ripped away from us."

He has not been back to the site as he cannot bear to see it as an empty shell.

President Jair Bolsonaro sent sympathies to France on Monday, but has previously emphasised that he cannot "work miracles" to rebuild Brazil's national museum. "It has already burned - what do you want me to do?" he said last year.

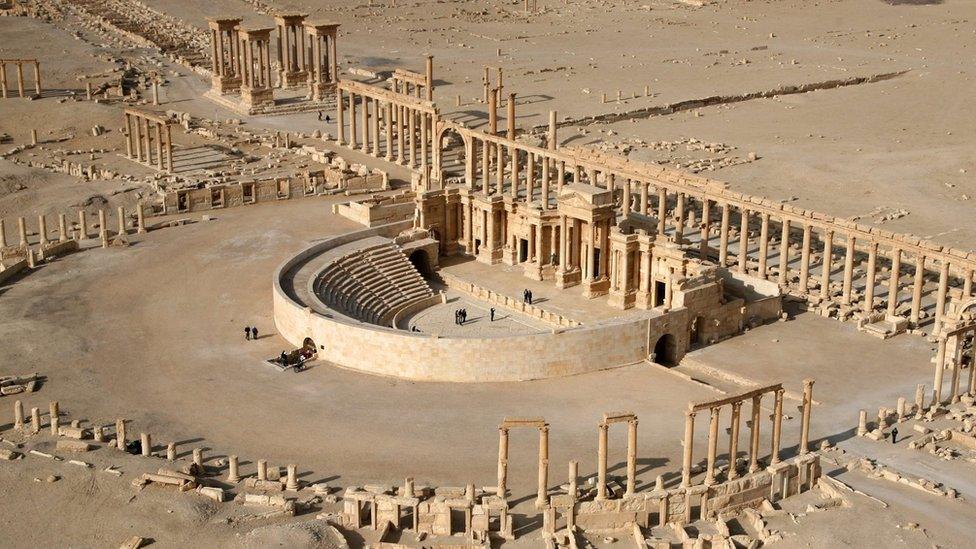

Syria: Palmyra

The Roman Theatre, part of the ancient city of Palmyra, seen in 2009

Syria does not have the luxury to consider rebuilding its lost culture amid its civil war. The conflict has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and destroyed many of its most precious cultural sites.

Among these is the ancient city of Palmyra. Photographs of it lying in ruins made international headlines in 2017.

"It's controversial," says Khaled Nashar - a Syrian who left the country in 2015 and is now based in the UK. He is referring to how Syria talks about its cultural losses. "One could think it is selfish to look at the loss of 'some stones' and not the loss of people."

But can both feelings co-exist?

Hazza Al-Adnan, a lawyer turned journalist living in Idlib, describes it as a different sort of sadness. "It is a kind of regret. It is not the same grief as when people die," he says.

Einar Bjorgo from the UN satellite programme says the image confirms the destruction of the temple

He lives in one of the last remaining rebel strongholds. "Next to the city where I live, there is a Roman archaeological village called Shansharah. The war has destroyed much of it and then turned into a camp for the displaced," he says.

He also remembers the day he first heard that Palmyra had been ruined, and how it still stunned him - even amid such constant disaster. "It was a shocking event. Isis does not give any value to civilisation and human history," he says, adding that the fact that it was deliberate made it much worse.

Mr Nashar agrees that it is hard to process. He says: "The feeling of sadness is even greater when you realise the country has not been only losing its future, but also a significant part of its past."

Haiti: Presidential Palace in Port-au-Prince

Destroyed Presidential Palace in Port-au-Prince, pictured in January 2010

Business student Naomi Handal, from Haiti, lived through her country's 2010 earthquake, and now lives on the same street as the Notre-Dame in Paris.

"The hard thing about Haiti was knowing the destruction came from natural causes. It was not an accident, there was no-one to blame, there was no reason why. It is like something that cannot be tamed. It could happen again," she says.

Around 160,000 people died in the magnitude seven quake. The government of Haiti estimated that 250,000 residences and 30,000 commercial buildings collapsed or were severely damaged.

Amid all that carnage, Ms Handal said there was a "disorientating" feeling that came from losing the presidential palace. "It symbolised the government and when you saw they were impacted too, you did not know whom to turn to. We were so lost."

There has been talk of rebuilding it, and France offered to help, but the proposal split opinions. Some feel there are still too many other priorities.

"The symbolism of the National Palace is very important for Haitians," says Eveline Pierre, executive director of the Haitian Heritage Museum, based in Miami. "Haiti was the first black nation to gain independence and the palace represented this for each individual. That is something that cannot be taken away."

She says many other buildings were also lost, including Port-au-Prince Cathedral and the Holy Trinity Cathedral, with its important murals of Biblical characters depicted with black skin. "There are many cultural losses that were, for sure, undocumented and no-one knows the full extent," says Ms Pierre.

As of Tuesday night, Ms Handal has been unable to return to her Paris apartment.

"It is sad, a tragedy," she says. "But around the world, there are so many worse things going on. It sounds so blunt to say it. But nobody died."

She worries now about the small businesses around her apartment, because they rely on tourism.

Germany: Dresden's Frauenkirche

Dresden's Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) was destroyed by bombing in World War Two and left in ruins for decades.

After the reunification of Germany in 1990, its reconstruction became a metaphor for reconciliation. It was finished in the mid-2000s, thanks to a €180m ($217m) project, mostly based on private donations.

Raka Gutzeit, a retired English teacher, has lived in Dresden since 1994. "We were all very moved when the renovation started," she says. "It was based on so much goodwill. There were workers from all over Europe, working all hours. It was beautiful to watch."

Some people she knew moved back to the city because of their emotional attachment to the Frauenkirche.

Dresden Frauenkirche as it looked in 1985

She admits it has taken a while for the new building to blend into the city. "It needed some greenery around it and it looked so bright at first," she says. "It is still becoming part of people's lives again."

David Woodhead, a former trustee from the Dresden Trust, a British organisation that helped raise funds for the project, says the Frauenkirche has the same sort of significances for the people of Dresden as Notre-Dame has for Parisians.

"It was a prominent part of the Dresden skyline, featuring in so many 18th Century paintings," he says. "During the 1945 bombing raids, a firestorm caused the original building to melt. Sandstone melts at 800C (1470F) and temperatures were said to have reached 1000C, so it imploded."

It was something no-one thought would be possible and it created a profound sense of something being "missing".

He says there was controversy over whether it should be rebuilt in the same way or take a new form, but ultimately its Baroque grandeur was restored. "It is not intended as a war memorial, but to be looking forward," he says.

Ms Gutzeit agrees. "Notre Dame is much bigger and older than Frauenkirche, and it has much more international status," she says. "But I hope Dresden's story brings hope to Parisians."

- Published15 April 2019

- Published17 April 2019

- Published3 September 2018

- Published16 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019