Seismic change: How Covid-19 altered world events in 2020

- Published

The year 2020 has been like no other. The coronavirus infected more than 67 million people, impacted 80% of jobs, and placed billions in lockdown.

It's tempting to imagine how 2020 would have turned out differently without a pandemic. What extra time would we have had with loved ones? What birthdays, weddings and milestones did we miss?

And while the crisis affected all of us personally, it also shaped news events around the world, with knock-on effects for millions.

Here are just four political issues, from four continents, which were altered by the pandemic.

1. The US election

The presidential election was meant to look very different. There should have been raucous rallies, and busy trips up and down the campaign trail.

Instead, the pandemic meant in-person rallies were delayed, and Joe Biden accepted the Democratic nomination in a near-empty room. Several attendees at a White House event became infected - while the president himself was dramatically flown to hospital after testing positive.

Experts believe there are various reasons why Donald Trump lost - but his handling of the pandemic was one of the biggest factors.

"It's clear the impact of the pandemic hurt Trump considerably," says Alan Abramowitz, political science professor at Emory College. Mr Trump failed to introduce adequate measures, and "to some extent discouraged" public health guidelines like social distancing and mask wearing, he says, turning off enough voters in swing states to tip the balance in Mr Biden's favour.

Ironically, Prof Abramowitz adds, people typically rally behind the president in a crisis. "If Mr Trump had addressed the pandemic seriously and effectively, I think he would have won the election pretty easily."

The pandemic also caused an economic downturn, which typically hurts incumbent presidents.

Allan Lichtman, a historian who devised a "13 keys" system that correctly predicted each presidential race since 1984, called the 2020 election for Joe Biden in August - on the basis of several factors, including the short-term and long-term economy.

"It was Trump's failed response to the pandemic that resulted in his defeat," Prof Lichtman, a professor of history at American University, says. Mr Trump downplayed the pandemic and so failed to contain infections quickly, which "cost him the short-term economic key and the long-term economic key".

Covid-19 meant the Democratic party moved most of their campaigning online - which may have also helped the Biden campaign.

Joe Biden accepted the Democratic nomination in a near-empty room, at a virtual congress

"Biden is memorable for making gaffes and misspeaking," says Miles Coleman, associate editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball, a political analysis newsletter at the University of Virginia.

The pandemic meant Mr Biden adopted a lower profile - and the election became "just an up or down vote on Trump", rather than "a choice between two candidates".

However, Mr Coleman adds, the fact Republicans continued with traditional in-person campaigning also meant "Trump gained with non-white voters in rural areas where people may not have the best internet - where you need to go door to door to reach voters."

Finally, Prof Lichtman believes the pandemic also helped drive the highest voter turnout in more than a century. The pandemic "created a real sense of national emergency… I think that convinced American people - both pro-Trump and pro-Biden - that this election was the most critical event of their lifetime."

2. Hong Kong's protests

In 2019, the world was gripped by an unfolding crisis in Hong Kong. The international financial centre saw near-weekly pro-democracy protests, often involving clashes with police, tear gas, and on occasion live bullets being fired.

While the demonstrations drew condemnation from Beijing and some businesses, the public largely appeared sympathetic - as shown in local elections in late 2019 where pro-democracy groups won by a landslide. Yet by 2020, the streets of Hong Kong were mostly quiet, the movement became subdued, and pro-democracy legislators either resigned - or fled the territory altogether. What changed?

The pandemic, which hit Hong Kong in January, led to a decline in demonstrations at the start, says Joey Siu, a student activist. "Hong Kongers are aware of the seriousness of the virus, given that we've had experience of the 2003 Sars outbreak."

However, the first and second waves of the pandemic were contained relatively quickly. The greater impact, analysts argue, came from how the pandemic led to strict public gathering guidelines - which were also used to penalise people at demonstrations.

Victoria Hui, a politics professor at Notre Dame University, says the authorities had always wanted to stop the anti-government protests, and "the pandemic gave the authorities an excuse" to do so under the guise of public health. Several pro-democracy activists have been fined, and protests banned, under social distancing guidelines.

Ms Siu says many had previously been willing to risk taking part in unauthorised demonstrations as there was still "a chance that we wouldn't get arrested, and a chance we could win at court".

"But now, with the public gathering ban, police are able to prosecute anybody who seems to be taking part in a pro-democracy protest, and fine you HK$2,000 ($260; £190)."

The government says its regulations are based on science, and needed to prevent infections.

An annual candlelit vigil commemorating the Tiananmen massacre was among those banned amid coronavirus restrictions

Then there were two major developments - the imposition of a sweeping national security law, and the postponement of parliamentary elections - that are widely seen to have restricted Hong Kong's pro-democracy movement.

The national security law made "inciting hatred" of the government, calling on countries to impose sanctions on Chinese officials, or using certain protest slogans, offences punishable by life imprisonment. Beijing has long said that such a law is needed to protect Hong Kong's integrity - but some argue that the timing of the law, which was finally introduced in May, was "fundamentally shaped by Covid-19".

"Beijing calculated that the rest of the world would be preoccupied," says Prof Hui.

The impact of the legislation was instant. Some pro-democracy groups disbanded, and shops took down posters supporting protesters. Activists became much, much more afraid to protest, says Ms Siu.

Supporters of the legislation, however, argued it was needed to restore stability after a year of often violent protests.

Hong Kong's Ronny Tong defends new security law

A month later, amid a third wave of infections, the government announced that legislative elections would be postponed by a year - despite some health experts saying it was still possible to hold polls safely. The government said the postponement was necessary given the "immense infection risk", and dozens of other elections around the world had also been delayed.

However, rights groups believed it was a political move, as pro-democracy groups had been hoping to win a majority in parliament. In subsequent months, several other pro-democracy politicians were charged by police, or disqualified altogether.

In November, all of Hong Kong's pro-democracy lawmakers resigned in protest - leaving the legislature with almost no dissenting voices for the first time ever.

3. Ethiopia's Tigray crisis

Many outside of Africa had not heard of Tigray, a region in northern Ethiopia, before 2020.

But in November, a conflict erupted between the Ethiopian government and the regional party, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) - leading to reports of hundreds dead, and more than 40,000 people fleeing into neighbouring Sudan. There had been fears the fighting could have destabilised the entire region.

One of the triggers for the crisis was the way the government handled the constitutional crisis that emerged after national elections were postponed due to Covid-19.

"The postponement of elections is one of the fundamental causes of this war," says Tsedale Lemma, editor-in-chief of the Addis Standard.

Under new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia had committed to democratic reforms in 2018. The national elections scheduled for August 2020 were the first opportunity for most opposition groups to compete, "after decades of absence from the political space", she says. "Everyone was excited."

"There were a lot of political tensions between rival groups, and although some had expressed concerns about possible post-election violence… people had hope that the elections would settle tensions."

When the pandemic hit in March, the electoral commission's initial decision to postpone the vote was accepted by most opposition groups. However, it also sparked a constitutional crisis as the government's term was due to end in September.

The government failed to compromise with opposition parties about what should happen next, says Ms Tsedale. Instead, a partisan legal council made the decision to extend the government's term and postpone elections indefinitely until the pandemic was over - and this was voted through by parliament's upper house, which is completely controlled by the ruling party, she adds. This meant the government lost legitimacy with its rivals.

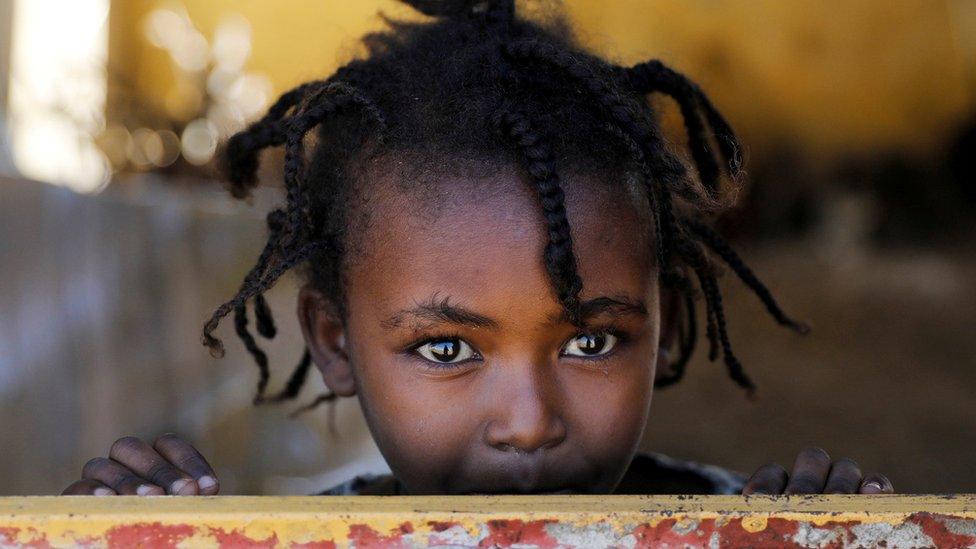

The crisis has forced more than 40,000 people from their homes

Comfort Ero, Africa programme director at the International Crisis Group, says "the pandemic and the decision around elections added more fuel to what was already a combustible situation."

Ethiopia was already in a "fragile transition", with tensions between the government and the regions, and threats of communal violence, she says. The opposition saw the postponement of elections "as another example of the prime minister not consulting with his rivals and acting unilaterally".

In response, the TPLF - which already had long-standing tensions with Mr Abiy - held its own regional elections on 9 September, in defiance of the federal government.

"That was the straw that broke the camel's back - the TPLF no longer recognised the central government, while the federal government refused to recognise the TPLF - they entered a phase of mutual delegitimisation and after that, war was a matter of when, not if," says Ms Tsedale.

Ethiopian troops captured Tigray's capital in late November, declaring victory - but fighting has continued in parts of the region and the UN has warned of "an appalling impact on civilians". The conflict is "a tragic, sad outcome... we missed a golden opportunity of building politics built on consensus," Ms Tsedale says.

4. Israel's political crisis

In April, political observers began saying that the pandemic had "saved" Benjamin Netanyahu's political career, external.

Mr Netanyahu had just been sworn in for a fifth term as prime minister, in a unity government with his rival Benny Gantz. The country had been in a state of political limbo for almost a year - despite holding three elections between 2019 and 2020 - as no bloc had enough seats to form a ruling coalition.

In fact, in the most recent, March elections, Mr Gantz was invited to form a government first, external, as he had a slim majority of MPs backing him, united by the goal of ousting Mr Netanyahu.

However, the opposition "had difficulty forming a government because they came from a very wide range of parties - from right-wing nationalists to left-wing communists," says Anshel Pfeffer, a commentator for Haaretz newspaper.

Then the pandemic arrived, while Mr Netanyahu was still acting as caretaker leader.

"People suddenly felt there was a state of emergency, and Netanyahu took charge of Covid policy, saying he was the only person leading the country in an emergency," Mr Pfeffer says. "The pandemic came at the best possible political timing for Netanyahu - it certainly helped put more pressure on Gantz to join him."

Mr Gantz, who had vowed never to sit in government with Mr Netanyahu as prime minister, defended his U-turn, saying "these are not normal times".

Under the terms of the unity government, Mr Netanyahu and Mr Gantz would rotate as prime minister, with Mr Netanyahu going first. The agreement was seen by many as a victory for Mr Netanyahu, who had defied opponents' calls to step down after being charged with corruption months earlier. He denies accusations of bribery, fraud and breach of trust.

Protesters have rallied against Mr Netanyahu's alleged corruption and handling of the pandemic

The pandemic brought Mr Netanyahu breathing space, says Tal Schneider, diplomatic correspondent at Globes. "The entire problem behind the scenes is the criminal trial - he just looks to gain more time."

By contrast, she added, Mr Gantz no longer posed a political threat because he was seen as having "cheated his voters" and his base by joining Mr Netanyahu in government.

And the unity government did not stay united for long - just eight months later, it collapsed amid a row over state budgets.

Israeli voters will have their fourth election in two years in March, and Mr Netanyahu has vowed to return with a "huge win".

Illustrations by Katie Horwich, external

- Published20 December 2020

- Published15 December 2020

- Published21 December 2020