COP26: New global climate deal struck in Glasgow

- Published

Alok Sharma fights back tears as Glasgow Climate Pact reached

A deal aimed at staving off dangerous climate change has been struck at the COP26 summit in Glasgow.

The Glasgow Climate Pact is the first ever climate deal to explicitly plan to reduce coal, the worst fossil fuel for greenhouse gases.

The deal also presses for more urgent emission cuts and promises more money for developing countries - to help them adapt to climate impacts.

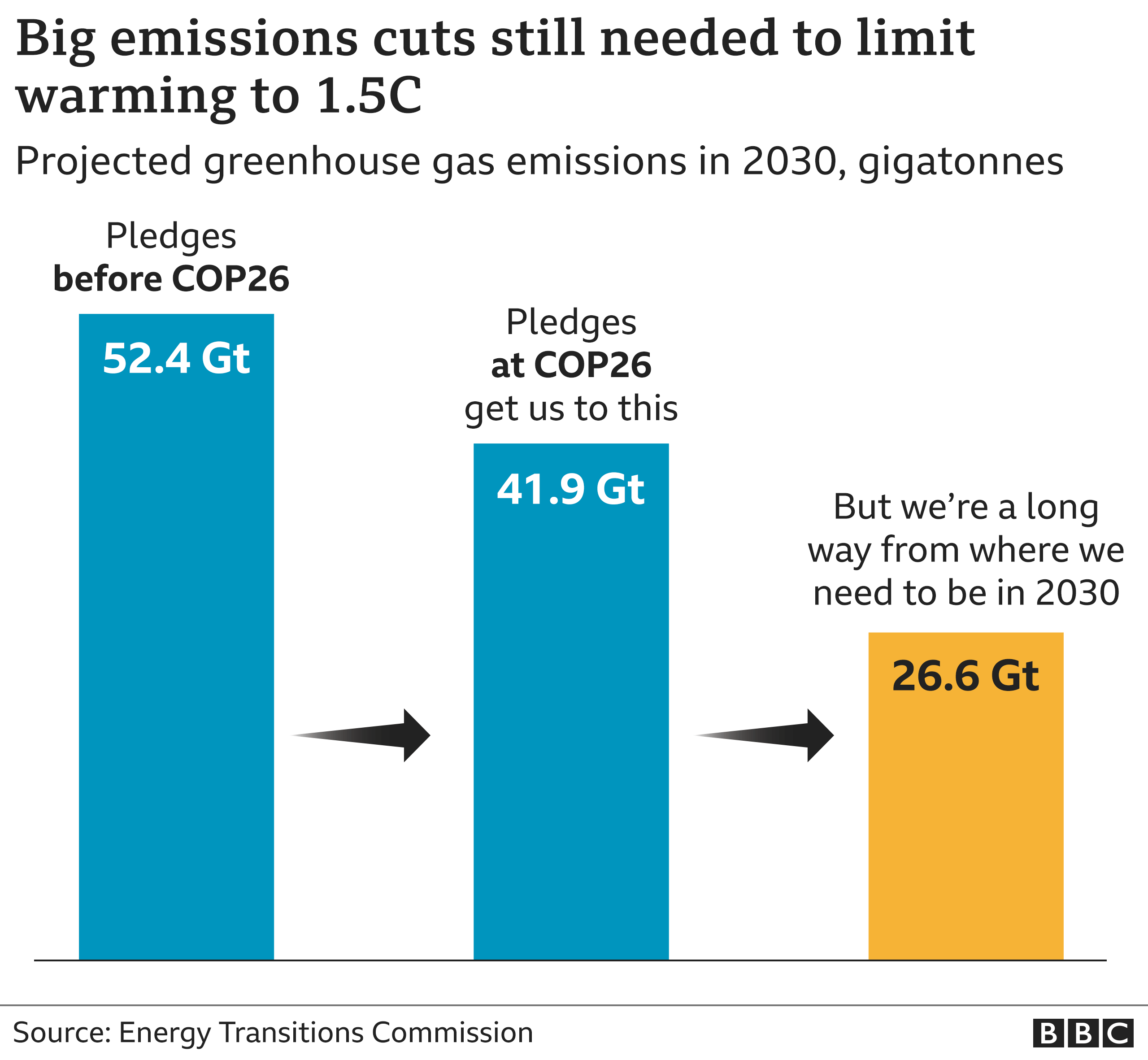

But the pledges don't go far enough to limit temperature rise to 1.5C.

A commitment to phase out coal that was included in earlier negotiation drafts led to a dramatic finish after India and China led opposition to it.

India's climate minister Bhupender Yadav asked how developing countries could promise to phase out coal and fossil fuel subsidies when they "have still to deal with their development agendas and poverty eradication".

In the end, countries agreed to "phase down" rather than "phase out" coal, amid expressions of disappointment by some. COP26 President Alok Sharma said he was "deeply sorry" for how events had unfolded.

He fought back tears as he told delegates that it was vital to protect the agreement as a whole.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he hoped the world would "look back on COP26 in Glasgow as the beginning of the end of climate change".

"There is still a huge amount more to do in the coming years. But today's agreement is a big step forward and, critically, we have the first ever international agreement to phase down coal and a roadmap to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees," he said.

John Kerry, the US envoy for climate, said it was always unlikely that the Glasgow summit would result in a decision that "was somehow going to end the crisis", but that the "starting pistol" had been fired.

Meanwhile, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the planet was "hanging by a thread". "We are still knocking on the door of climate catastrophe... it is time to go into emergency mode - or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero."

As part of the agreement, countries will meet next year to pledge further major carbon cuts with the aim of reaching the 1.5C goal. Current pledges, if fulfilled, will only limit global warming to about 2.4C.

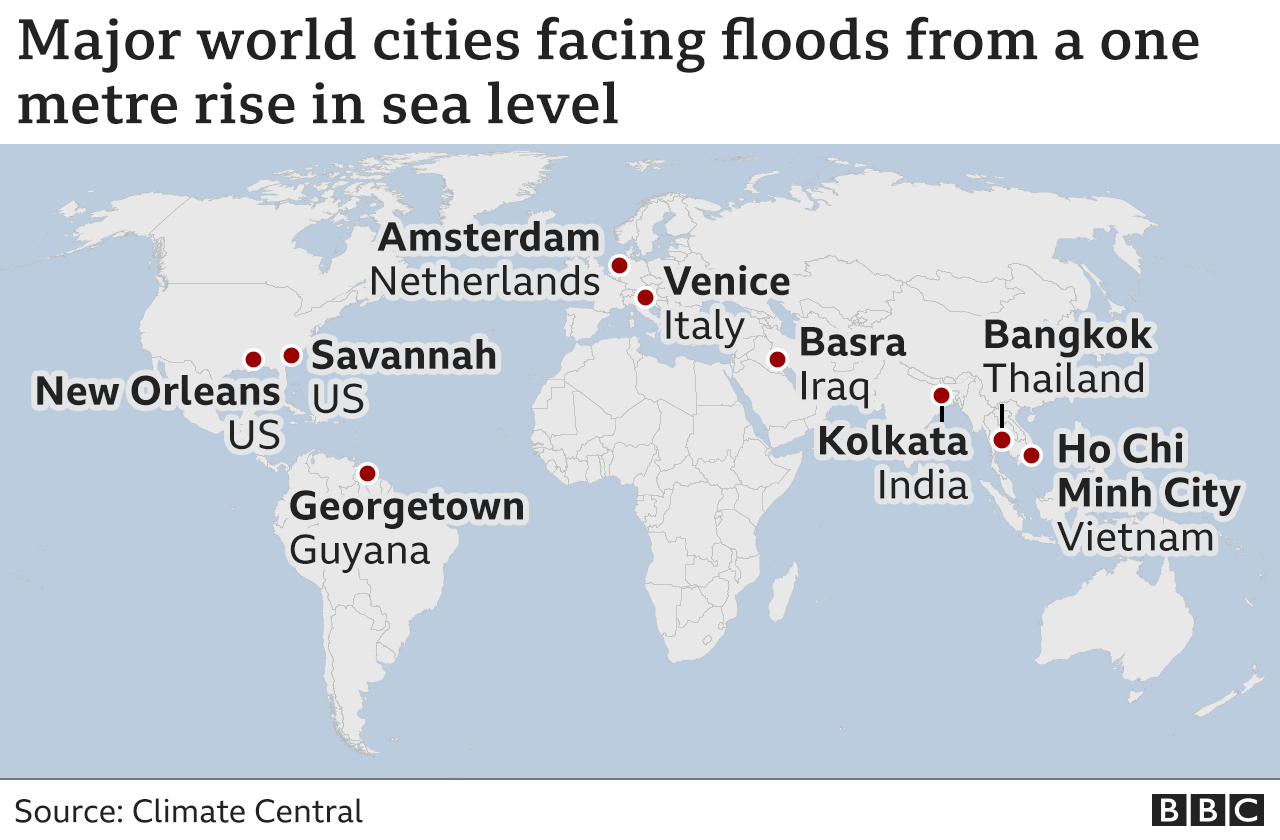

If global temperatures rise by more than 1.5C, scientists say the Earth is likely to experience severe effects such as millions more people being exposed to extreme heat., external

Main achievements of the deal:

Re-visiting emissions-cutting plans next year to try to keep 1.5C target reachable

The first ever inclusion of a commitment to limit coal use

Increased financial help for developing countries

"We would like to express our profound disappointment that the language we agreed on, on coal and fossil fuels subsidies, has been further watered down," Swiss environment minister Simonetta Sommaruga said. "This will not bring us closer to 1.5C, but make it more difficult to reach it."

Despite the weakening of language around coal, some observers will still see the deal as a victory, underlining that it is the first time coal is explicitly mentioned in UN documents of this type.

Coal is responsible for about 40% of annual CO2 emissions, making it central in efforts to keep within the 1.5C target. To meet this goal, agreed in Paris in 2015, global emissions need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 and to nearly zero by mid-century.

"They changed a word but they can't change the signal coming out of this COP - that the era of coal is ending," said Greenpeace international executive director Jennifer Morgan.

However, Lars Koch, a policy director for charity ActionAid, said it was disappointing that only coal was mentioned.

"This gives a free pass to the rich countries who have been extracting and polluting for over a century to continue producing oil and gas," he said.

Sara Shaw, from Friends of the Earth International, said the outcome was "nothing less than a scandal".

"Just saying the words 1.5 degrees is meaningless if there is nothing in the agreement to deliver it. COP26 will be remembered as a betrayal of global South countries," she said.

Finance was a contentious issue during the conference. A pledge by developed nations to provide $100bn (£75bn) per year to emerging economies, made in 2009, was supposed to have been delivered by 2020. However, the date was missed.

It was designed to help developing nations adapt to climate effects and make the transition to clean energy. In an effort to mollify delegates, Mr Sharma said around $500bn would be mobilised by 2025.

Scientists say extreme weather events, such as severe flooding, are becoming more frequent because of climate change

But poorer countries had been calling throughout the meeting for funding through the principle of loss and damage - the idea that richer countries should compensate poorer ones for climate change effects they are unable to adapt to.

This was one of the big disappointments of the conference for many delegations. Despite their dissatisfaction, several countries that stood to benefit backed the agreement on the basis that talks on loss and damage would continue.

Delegations pushing for greater progress on the issue included those from countries in Africa, such as Guinea and Kenya, as well as Latin American states, small island territories and nations in Asia such as the Philippines.

Lia Nicholson, delegate for Antigua and Barbuda, and speaking on behalf of small island states, said: "We recognise the presidency's efforts to try and create a space to find common ground. The final landing zone, however, is not even close to capturing what we had hoped."

Shauna Aminath, environment minister for the low-lying Maldives, said: "We have 98 months to halve global emissions. The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees is a death sentence for us."

Climate stripes visualisation courtesy of Prof Ed Hawkins and University of Reading.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

Related topics

- Published13 November 2021