South Africa’s ‘Red Pimpernel’ recalls armed struggle

- Published

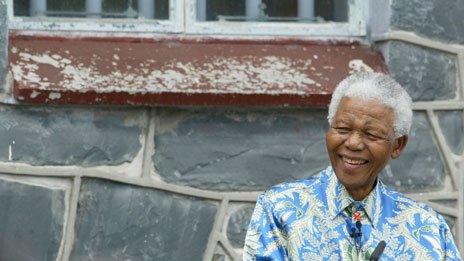

The ANC's military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, was launched on 16 December 1961

Fifty years ago on a summer evening in the South African city of Durban, 23-year-old Ronnie Kasrils was sweating as he crawled through a field of maize trying to avoid detection.

He was one of the activists from the African National Congress' armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), formed in 1961 to carry out attacks against government installations.

Nearby was a municipal labour office. Four watchmen were on duty, sitting around a fire drinking as they whiled away the night shift.

Mr Kasrils' mission was to plant an explosive device against the front door of the building.

"Using a World War II approach, I sandbagged it to get the maximum effect," he remembers.

"The timing device was a Heath Robinson affair that involved a condom and a capsule containing sulphuric acid.

"I hung around the centre of town until I heard the sound of the explosion. Then I caught a bus and went home.

"I trembled a lot and I was glad it was over, but I was elated. As I waited for the morning papers, I had a very large glass of whisky to relax."

The ANC's momentous decision five decades ago to abandon its peaceful resistance to apartheid set South Africa on a new path.

Radical

Mr Kasrils grew up in Johannesburg. His grandparents had been Jewish immigrants.

As a university student in 1960, he was deeply influenced by the Sharpeville massacre, when 69 unarmed protesters were shot dead by the police while taking part in a demonstration against the pass laws.

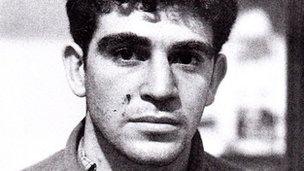

Ronnie Kasrils' cheek was grazed by a bullet after a clash with would-be assassins in Durban in 1961

"I decided I must do something about this dreadful racism. I came into contact with the African National Congress (ANC) and a female cousin also linked me into the South African Communist Party (SACP)."

Both organisations had been outlawed by the white minority government and driven underground.

During the course of 1961, as South Africa left the Commonwealth, ANC leaders including Nelson Mandela began to discuss whether they should continue the non-violent struggle or opt for a more radical means of fighting apartheid.

By now, Mr Kasrils had moved to Durban where he was establishing himself as a daring-do activist.

"I had been very busy painting slogans on walls and handing out leaflets secretly. One day I was approached by MP Naicker, a member of the Communist Party and the Natal Indian Congress.

"He told me that change was coming, as it was not going to be possible to defeat apartheid by peaceful means. He said the movement needed young people like me."

'Complete amateurs'

There was still much soul-searching within the ANC about the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), although not for young Mr Kasrils.

"I embraced it all instantly. It seemed absolutely natural to me and I made it clear I'd do everything I could to make a success of it."

MK's manifesto - published on 16 December 1961 - stated that Umkhonto we Sizwe was a new independent body made up of South Africans of all races. Only later did it come to be accepted as the ANC's armed wing.

"I was introduced to the people who made up the MK Regional Command in the province of Natal," says Mr Kasrils.

"Our practical experience was next to nothing. It was drawn from my school science experiments. None of us knew about explosives, but there were people who'd taken part in the Second World War.

"One was Jack Hodgson who'd served in North Africa, so we nicknamed him 'The Desert Rat' when he was sent down from Johannesburg to teach us the basics of bomb making.

"We met in the back room of a safe house to learn the theory, and the live experiments took place in the sugar cane fields.

"We were complete amateurs and we had to do months of training and reconnaissance."

The Sharpeville massacre in 1960 deeply influenced Ronnie Kasrils

MK leaders selected 16 December for the first wave of nationwide sabotage attacks.

It was an important historical date for white Afrikaners, having been the day when their forebears, the Voortrekkers, fought off Zulu warriors at the Battle of Blood River in 1838.

In Durban Mr Kasrils and his colleagues had identified three targets in the city.

"None of our explosives worked very well," he reflects. "Some windows were broken, and at the municipal offices our 'big bomb' only managed to blow the door off its hinges.

Nonetheless, the symbolism was there and we felt it was an historic deed for a just cause."

Mr Kasrils says the young saboteurs worried about the dangers of what they were doing. He says that - in this new method of struggle against apartheid - they took precautions to avoid civilian casualties.

Fighting in exile

Public opinion was divided when news of the first MK operations spread.

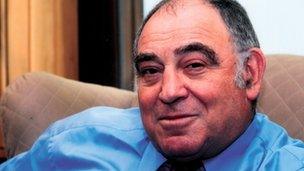

Mr Kasrils once served as head of MK's intelligence and as intelligence minister after apartheid ended

Mr Kasrils says the government and the press began to rant about "terrorism and Communism", while claiming black South Africans were "overjoyed".

However, he admits there was still a passionate debate within the Communist Party about the resort to violence.

Mr Kasrils' cousin and her husband were among those who insisted that the bombings would not serve the movement well.

Umkhonto we Sizwe continued to grow but in 1963 the entire leadership of the MK high command was arrested at a hideout in the Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia.

Mr Mandela and other leaders - including Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and Ahmed Kathrada - were sentenced to life imprisonment.

But Mr Kasrils managed to escape the police net and went into exile abroad.

Over nearly three decades many young South Africans followed in his footsteps and left the country to undergo further military training.

Mr Kasrils, who became known as "The Red Pimpernel", remained at the heart of the fight against apartheid.

"The armed struggle was not the only factor that brought change in South Africa but it was one of the elements that eventually helped to force the white government to see reality and open the way to negotiations and democracy," he said.

Peter Biles' interview with Ronnie Kasrils has been broadcast on the BBC World Service's Witness programme. You can download a podcast of the programme or browse the archive.

- Published18 July 2011

- Published8 June 2013

- Published9 July 2024

- Published2 November 2011