South Africa's Jacob Zuma under pressure as ANC turns 100

- Published

As South Africa's ruling party celebrates its centenary, William Gumede, professor at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, assesses the performance of its current leader for the BBC's Focus on Africa magazine.

South Africa's ruling African National Congress (ANC) - the continent's oldest liberation movement - is having a bitter-sweet 100-year celebration and it is as divided as it has been in living memory.

Central to the divisions is President Jacob Zuma who appears intent on pushing for a second term.

His critics say this is to pre-empt an unceremonious recall from the country's presidency by ANC members and to prevent enemies from attempting to prosecute him again for his alleged involvement in South Africa's controversial 1999 arms deal, external.

Critics also suggest he wants to safeguard the burgeoning business interests of his family.

The ANC is staging a huge party to celebrate its 100th anniversary

Mr Zuma's backers retort that he is unfairly maligned by the media in particular and point to his resilience and "common touch" as reasons for his political survival.

Julius Malema, the controversial president of the ANC Youth League and a thorn in Mr Zuma's side, was suspended from the party last November for five years for bringing the ANC into disrepute, sowing divisions and undermining the presidency.

Mr Malema is appealing against his sentence and is planning to take his fight all the way to the ANC's national elective conference in Bloemfontein in December 2012.

The suspension of Mr Malema opens the path for Mr Zuma to be re-elected as president for a second term.

Mr Malema and the ANC Youth League not only actively opposed Mr Zuma's second-term aspiration; they were also the conduit for others to express opposition to Mr Zuma's leadership.

Second term?

The ANC's centenary year may be one of its most bumpy with angry ANC youth league members' rebelling against Mr Zuma's suspension of Mr Malema, leadership battles between various factions over control of resources in government and the party, and a likely rise in protests from disenchanted poor communities against sluggish public service delivery.

All this in the midst of rising economic hardships resulting from the global financial crisis.

The real danger for Mr Zuma is whether Mr Malema can convincingly portray his suspension to the disenchanted and especially the youth, as an attempt by the president to marginalise a "spokesperson" of the poor.

This is a tactic Mr Zuma has used himself. When battling former President Thabo Mbeki, he successfully portrayed his sacking for alleged corruption as being motivated by his pro-poor stance.

In young democracies such as South Africa, where democratic institutions are still in their infancy, the example set by political leaders is crucial.

Mr Zuma was voted in as ANC president in 2007 at the party's Polokwane conference. He replaced Mr Mbeki after promising he would govern more democratically.

This was after Mr Zuma and his supporters went on the offensive through attacks on the country's judiciary and media in order to ensure corruption charges against him were quashed.

Once in power, Mr Zuma has shown scant regard for South Africa's institutions of democracy.

For instance, the president is ramming through a controversial information bill, despite widespread opposition from civil society.

This gives the government broad powers to classify almost any information involving a state agency as being in the "interests of national security".

The legislation will penalise whistle-blowers, journalists and activists who possess, disclose or even attempt to uncover protected information, and who refuse to reveal the sources of any classified material with jail terms of up to 25 years.

Furthermore, Mr Zuma has advocated the establishment of a media appeals tribunal which will have the power to sanction journalists for "misconduct".

No direct oversight

Worryingly, South Africa's parliament has no direct oversight over the South African presidency; and both Mr Mbeki and now Mr Zuma have opposed efforts to change this.

Mr Zuma has also sparked furious debate by insisting that the judiciary should not "interfere" with the executive's "sole discretion" to decide policy.

In August 2011 Mr Zuma's close political ally and ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe declared that the courts were acting as if they were the political opposition by "interfering" with the "right" of elected officials to make policies and laws.

In spite of his suspension, Julius Malema was recently elected to a leadership position in the party

This may stem from the fact that Mr Zuma's government has lost a number of cases in the country's constitutional court.

For instance, businessman Hugh Glenister successfully challenged the government's decision to scrap the elite crime-fighting unit - the Scorpions.

And fearing the court would rule in favour of activist Terry Crawford-Browne, who campaigned for the government to establish a judicial commission of inquiry into corruption in South Africa's controversial arms procurement deal, Mr Zuma set up his own board of enquiry with his own terms of reference.

Mr Zuma also attracted controversy by pushing through the appointment of Judge Mogoeng Mogoeng as head of the constitutional court.

Mr Mogoeng supported the death penalty during the apartheid era, and has been accused by the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) of having a "mindset" that is "not in line" with the constitution.

Mr Zuma, though, has argued Mr Mogoeng is highly experienced.

South Africa's globally admired constitution is increasingly talked about by those in the Zuma administration as being either against development or an obstacle to faster public service delivery.

In fact Jimmy Manyi, Mr Zuma's former spokesman, has said that "it appears the constitution does not support the transformation agenda in this country."

Mr Manyi cites freedom of expression in the constitution as an example of "a problem."

'Predatory state'

Throughout his presidency, Mr Zuma has been accused of ensuring his family members and associates benefit from "mega" government and private sector tenders but, despite the president saying he would welcome a discussion in parliament on this, the ruling party seems reluctant to confront the matter head-on.

Albertina Luthuli, who was until recently a member of parliament, talks about the ANC as its 100th anniversary is commemorated.

In August, the ANC speaker in South Africa's parliament, Max Sisulu, rejected a request by the opposition Democratic Alliance for a debate on the issue.

One ANC youth leader has described Mr Zuma's presidential style as that of a traditional African chief, using his office to distribute state patronage to allies, friends and family.

Cosatu secretary-general Zwelinzima Vavi says that South Africa is "slipping into a 'predatory state' where a new tier of leaders believe it's their turn to feed." He adds: "In the process, we have battles of short-term interests."

The ANC's leadership succession battle in 2007 saw rival factions often using state security agencies, the police and intelligence services to try to eliminate rivals.

At the height of the tussle, a state of paranoia reigned. Alarmingly, it appears that this is still happening - for instance, the alleged use of illegal phone-hacking, according to investigations carried out by the Mail & Guardian newspaper.

Mr Zuma comes from the ANC's intelligence wing, the most shadowy, secretive and heavy-handed organ of the party in exile. This culture of operation appears to be infiltrating the state and the ANC.

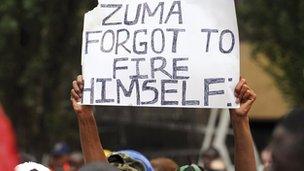

The president's credibility is questioned by some of his opponents

The rule of law is also increasingly seen as not applying to the political elite.

Days after Public Protector Thuli Madonsela found that the then Police Commissioner Bheki Cele, a key Zuma ally, had acted improperly in arranging a multi-million dollar lease for new headquarters from a friend, the police raided her office to search for documents related to the report.

However, Mr Zuma's subsequent cabinet reshuffle, in which he fired two ministers accused of corruption and suspended Mr Cele from his duties, has given the president a much-needed boost.

But a second presidential term for Mr Zuma is likely to continue on the same trajectory as the first: Paralysis in government as he pays back diverse backers, battered democratic institutions and the entrenchment of undemocratic values and behaviour.

These may take a very long time to undo.

- Published6 January 2012

- Published6 January 2012

- Published16 December 2011

- Published15 December 2011

- Published10 November 2011

- Published8 May 2024

- Published11 November 2011