Niger's complicated hunger crisis

- Published

Andrew Harding visited a hospital in a small town an hour from Niger's capital

In a small, neat hospital ward in the dusty town of Ouallam, 10 young children are lying on beds displaying the familiar signs of severe malnutrition - laboured breathing, papery skin stretched tight over ribs and back bones. Their anxious mothers hover over them.

Three-year-old Dauda Mahmoud has a tube attached to his nose, a hacking cough that shakes his fragile body, and a cocktail of ailments that include suspected tuberculosis. Two years ago, his brother died "from a fever, overnight," says his 22-year-old mother, Halima.

The annual hunger season is beginning once again in the vast, arid strip of land just below the Sahara desert, and the medics at Ouallam - a small town an hour's drive north of Niger's capital Niamey - have seen a sudden leap in admissions in the past week and are bracing themselves for an exceptionally tough few months before October's harvest.

"It will be bad - of course we are worried," says the senior nurse, Mustapha Aishatu.

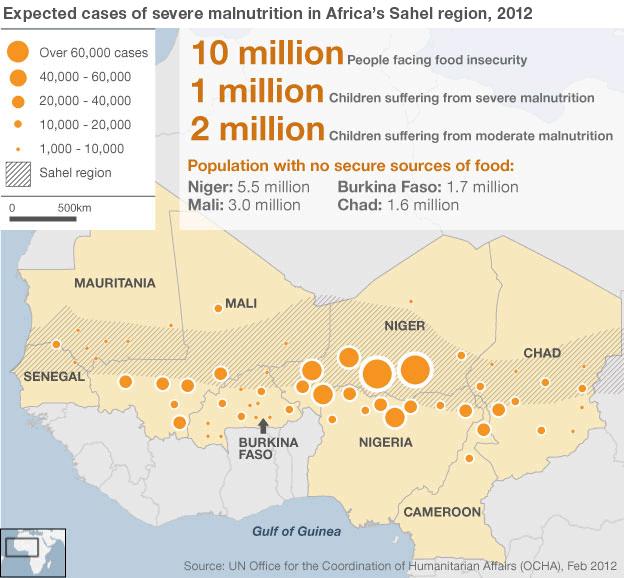

Already, international aid agencies are beginning to sound the alarm, publicising worst-case scenarios in an understandable bid to attract donations while there is still a chance to buy and stockpile food and supplies before the crisis reaches its expected peak somewhere between June and September.

The United Nations' World Food Programme expects that almost 400,000 children in Niger could find themselves so malnourished that they end up like those in Ouallam's hospital. Nearly one in 10 are likely to die as a result.

There is something shockingly and compellingly simple about the idea of a child dying of hunger. But here in Niger, the causes are often complex - and so are the solutions.

Those involved in fighting hunger here rattle off the contributing factors like ingredients in a grim recipe:

A failed harvest, which has undermined the gains of last year

Years of drought which have left many families in debt

A sharp spike in food prices at the market, blamed on a combination of oil politics in neighbouring Nigeria, speculation by traders, poor market integration and a lack of infrastructure

Regional insecurity, with a rebellion to the north in Mali and an insurgency to the south in northern Nigeria, leading to unexpected population movements in a fragile region that can't cope with such abrupt changes

A lack of education which results, for example, in mothers giving their babies dirty water to supplement breast milk, leading to diarrhoea - one of the quickest paths to severe malnutrition

Chronic poverty, which means poor basic health care, leaving children are vulnerable to disease

Population growth

Child marriages, which can result in premature or stunted babies and frail mothers

Climate change and desertification

And lurking behind all these factors is the biggest, most important one of all - the single, exponential ingredient that is usually responsible for turning a wretched situation into a famine or similar catastrophe: bad leadership.

It was the behaviour of Somalia's militant group, al-Shabab, that transformed last year's drought into a famine in the Horn of Africa, and it was Niger's repressive government that failed to acknowledge the scale of hunger in the country in 2005 before it was too late.

Today, the Sahel region remains crippled by weak governments, coups and other forms of political instability.

But Niger has suddenly emerged, after a coup in 2010, as a welcome and unexpected exception in a rough neighbourhood.

The new, democratic government was quick to detect the first signs that this year's food crisis would be particularly severe.

There is now "great co-operation", according to insiders, between Niger's authorities and a range of international donors, UN agencies and charities. For the first time, a co-ordinated, flexible response plan has been drawn up in response to the looming emergency.

"It's a welcome change," says WFP country director Denise Brown. "It has created a dynamic that could eventually lead to long-term change in the country. It's not just about today's crisis. It's about where it will take us to down the road."

That does not mean that children won't starve here this year. It does not mean that foreign donors will step in early enough to fill an 80% shortfall in the WFP's planned budget for the months ahead, and ensure that food supplies are in place in time.

But it is an encouraging start, in a wretchedly, chronically poor country.

- Published9 March 2012

- Published18 January 2012

- Published29 February 2012

- Published4 August 2023