Somalia's famine: One year on

- Published

- comments

The BBC's Africa correspondent Andrew Harding, who reported on last year's famine, has been back to Somalia

So, do you want the good news first… or the bad news?

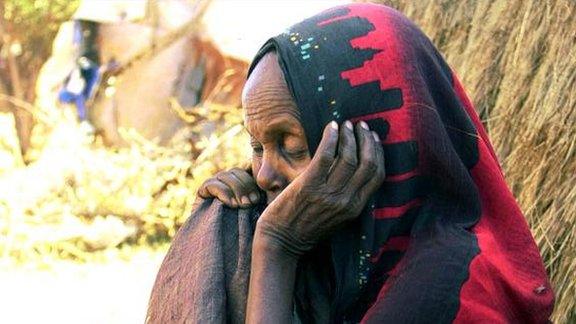

One year after the United Nations declared a famine in parts of Somalia, there is plenty to praise and even more to fret about in a country still grappling with conflict, drought, and the muddled politics of international aid.

It is almost exactly 12 months since I last visited Dolo - a shabby but relatively quiet little town near the border with Ethiopia, which was then swamped with civilians fleeing the famine zones.

Today, at first glance, not much seems to have changed. Still lots of men with guns, a bone-dry countryside, hundreds of threadbare makeshift tents, and - just as we drove into a UN camp - the familiar sight of weary new arrivals squatting in the dirt. Some 3,000 people are still coming here each month.

Forty-year-old Halima Hawana told me she had sold her small field to raise the money to make the journey. "The drought is back," she said through a local translator, "and al-Shabab threaten us. The security is no good."

'Still critical'

Despite losing some key towns in recent months to a haphazard series of offensives by Somalia's transitional government troops, foreign forces and local militias, the militant Islamist group al-Shabab still holds big chunks of southern Somalia. It was their reluctance to allow aid into their territory, combined with soaring inflation, which triggered the famine last year.

And yet, despite the on-going security concerns and the partial failure of the latest rains, there is also real progress here.

"The situation is still critical," said the UN's chief humanitarian coordinator for Somalia, Mark Bowden. "But things are improving. We do have things under control - we are better positioned. We are very unlikely to have [another] famine."

That is due to a number of factors. There was one decent rainfall in Somalia earlier this year - which led to a good harvest. Food prices - and despite its chaos Somalia is closely tied into global markets - have stabilised and inflation is under control. And finally there is what Mr Bowden called the "phenomenal generosity" of the international community following his declaration of a famine one year ago. Donors "should be very proud of themselves," he said.

A closer inspection of Dolo revealed some of the results of that generosity - large warehouses full of grain, as well as a brand new hospital and other infrastructure.

But what happens now that the famine is over? The "F word," as it is known in aid circles, signifies a shockingly grim event and one of the ultimate examples of a man-made catastrophe. But it is also - and I hope this doesn't come out the wrong way - one hell of a fund-raising tool.

"Statistically, the famine may be over now," said Sikander Khan, the head of Unicef Somalia. "But we are not out of the woods yet. We're concerned that just by declaring the famine is over, people may think everything is fine. It's not fine. One in five children is malnourished. Donors have been very generous but we need to sustain this momentum… to make these children resilient."

Which is why the UN is now clamouring for the rest of the $1.16bn ($740m) it says it needs to avoid another humanitarian disaster in Somalia this year.

'Self-sufficient'

But even while they are appealing loudly for more money, senior UN officials quietly acknowledge the flaws , externalin a funding system that seems driven by media headlines and geared towards the short term.

Adam Alil hopes his family may one day not have to rely on aid

"Emergency responses are always very expensive," said Mr Khan, sketching out his vision of a longer-term development strategy that would be "much cheaper and has far more impact".

And curiously, that vision is already taking partial shape in a field just outside Dolo - where a livid green expanse of corn, onions and other crops form an unexpected contrast with the surrounding scrubland.

Adam Alil is one of a group of farmers tending the fields, and guiding the water being pumped from the nearby river down a network of small irrigation channels.

"Once we harvest then we going to support our family so in future we might not need aid. We can become self-sufficient. I don't want to sleep - I want to work," he said, leaning on a metal crutch having lost one leg to a snake bite.

These fields, and 82,000 like them across Somalia, are being heavily supported - with seeds, and fuel for the irrigation pumps - by the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). According to the FAO's Somalia boss, Luca Alinovi, the project is working "quite successfully" even in areas of conflict and regions under al-Shabab control. But the FAO is hamstrung by a lack of longer-term funding.

"We need support for two or three years," to allow farmers to become self-sufficient, said Mr Alinovi, but the funding "is not yet there".

As we headed back to the air strip for the return flight, I saw Halima Hawana and the other new arrivals being processed by officials at the camp. Optimists will argue that the current upsurge in fighting is a sign that al-Shabab is on the verge of defeat, and point to the growing sense of security in the capital, Mogadishu. August is likely to be an important month in the city, as a new parliament takes shape.

But al-Shabab is a symptom of Somalia's problems as much anything else, and the pessimists have a better track record in this turbulent country. The darkest days of last year may be over, but it remains hard to imagine a quick or smooth end to Somalia's troubles.

- Published17 July 2012

- Published19 July 2012