Nigeria's precarious oil amnesty

- Published

The amnesty is allowing former militants to retrain in a variety of skills

An amnesty for thousands of militants in south-eastern Nigeria has brought relative stability to the region, enabling its huge oil industry to recover but, as the BBC's Will Ross reports, some are questioning how long the peace can hold.

"If I'd set eyes on you back in those days we would not be talking like this," says Tobine with a menacing smile. "I would have made a call to find one or two ways to make money out of you."

Tobine means he would have kidnapped me for ransom.

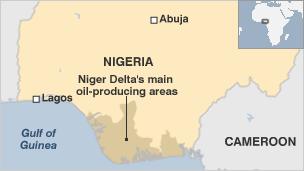

Until the 2009 amnesty agreement, he was a militant in the Niger Delta where rival gangs fought each other for supremacy and targeted the oil companies. The insecurity was costing Nigeria tens of millions of dollars every day as oil production was severely disrupted.

"We were doing some bad, bad things; raping, kidnapping busting the pipelines just to make money," says the man who fellow militants used to call Jah Rule.

Tobine is 25 and is reminded of these experiences every time he looks in the mirror. There is a deep vertical scar below his eye - a souvenir from the day he was attacked by a machete-wielding man from a rival gang.

But Tobine's life has taken a dramatic turn and now he hopes to get a job with one of the oil companies whose pipelines he once attacked. He is among a group of 40 trainees graduating from a pipeline-welding course in Port Harcourt.

"I'm doing great. I'm proud about myself, but I want to go higher. My parents are proud of me. I want to make them more proud," he says, adding he has no desire to return to the bush as he now wants to help his family, including his six-year-old daughter.

Anger issues

As the course ends, there is concern as to whether jobs will follow. There is a worrying lack of job opportunities.

"They say the idle man is the devil's workshop. I don't want my mind to go to any evil thing at all, so I have to look for something to do," says another trainee - 32-year-old Abiye Godgift.

It has not been an easy task for those who had the job of not only training the ex-militants, but also changing their whole attitude to life.

Tobine is proud of his new skills, but there is concern about employment opportunities

"These are people who in the past had questionable characters," says Ikioye Dogianga, the head of IK Engineering Global Ltd which trains personnel for the oil industry.

"They have stained their hands in blood and have done so many things, so it takes you a great deal to train them to the standard they are now.

"There were issues of them getting angry very quickly. They were highly temperamental. They felt they were the authority themselves," says Mr Dogianga who intends to offer jobs to the five best trainees in order to motivate the next class.

The amnesty was introduced in 2009 by the late President Umaru Musa Yar'Adua.

All 26,000 people who have benefited from the amnesty are entitled to a monthly allowance of approximately $400 (£255). For how long, no-one knows. This is an expensive undertaking with the government spending $400m this year alone.

The former militant leaders are now mostly based in the capital, Abuja, where they are living in relative luxury. Money was a key factor in ending the violence.

Although many are awaiting promised training, close to half the beneficiaries have been offered courses in a variety of skills from carpentry to marine engineering, and 20 people were sent abroad to learn to be pilots.

Not all the beneficiaries were perpetrators of the violence in the Niger Delta. Many were victims.

"When I was seven, my village was burnt down by militants who didn't want it to develop," says 17-year-old Blessing Ogunga who is studying for her O-levels at Emarid College in Port Harcourt.

Blessing Ogunga's father was a militant - she is now receiving an education

"I remember that Saturday morning. People said everybody should shift from the village as bad boys were coming to burn down the village."

Blessing dropped out of school at the age of 10 because her parents could not afford the fees.

"My dad became a militant as he wanted to get the money to send me to school. He wanted me, the first daughter of the family, to graduate, so I would be able to speak for the family, to stand with my rights and speak," says Blessing, who wants to be a computer engineer.

Time bomb

The result of the amnesty is that the Niger Delta is relatively peaceful and oil production has soared. The government says at the height of the militancy, only about 800,000 barrels a day were produced compared to the current output of around 2.3 million barrels.

But not everyone is convinced that the peace is permanent and there are fears that re-arming has been taking place in the Delta.

"This is a dangerous time bomb. <link> <caption>The Boko Haram issue in the north of Nigeria</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13809501" platform="highweb"/> </link> is child's play compared to what is going to happen in the Niger Delta," says Onengiya Erekosima, the reintegration and peace-building officer in the amnesty commission.

Having played a role in persuading militants to embrace peace, he warns that a large number of guns are still in dangerous hands and says the whole amnesty has become a money-making exercise.

"Militant leaders are pretending they had more boys following them than they really had and they are doing it to make money.

"They are coming to the amnesty commission to say 'the names we brought were not the real people' and now they want to change the names," says Mr Erekosima.

There is also concern that the amnesty programme was not rolled out to all areas of the Niger Delta.

Just prior to the 2009 amnesty, there was no violence in the area known as Ogoniland. There has also been no oil production there since 1993 when Shell pulled out following years of agitation by the local population calling for a fair share of the oil wealth and an end to pollution.

"The amnesty programme was lopsided. The Ogoni people did their own agitation through peaceful advocacy… while others resorted to violence. This violence appears to have been responded to through the amnesty," says Bariara Kpalap, the chair of the region's Kegbara-Dere town council.

"In a situation where the government only looks for issues that relate to the flow of oil in the Niger Delta without thinking of addressing poverty… then peace in the Niger Delta will be elusive," says Bariara Kpalap who also feels the amnesty has favoured the Ijaw people - President Goodluck Jonathan's own community.

President Jonathan has given his full backing to the programme and has ensured the money is flowing to the Delta. But the amnesty has not been gazetted into law and some feel that makes it precarious.

"I see the future as very bleak because my impression is that if President Goodluck Jonathan is no longer in power, the co-operation the federal government has been receiving from the Niger Delta may no longer be there," says Erabanabari Kobah, an environmental campaigner.

"Some are still holding their guns and are watching what will happen," he warns.