Viewpoint: Does race matter in South Africa?

- Published

In mid-August the national airline, South African Airways (SAA), put up online advertisements for the training of cadet pilots.

The trade union Solidarity put in two applications with exactly the same qualifications and backgrounds except for one crucial fact: One was white and the other black.

The white applicant immediately received a rejection letter while the black applicant progressed up the vetting system.

A massive storm broke out over the issue, with South Africa's largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, saying the practice takes "our reconciliation project backwards".

Spokeswoman Natasha Michael was quoted as saying racial discrimination had been "the animating idea of apartheid" and had no place in a democratic South Africa.

This is a familiar narrative in a South Africa that is trying to redress the inequities of apartheid's past and build an egalitarian country.

Yet the SAA story becomes somewhat more complex when one considers the facts at the national airline.

"Currently, 85% of SAA pilots are white, of which 7.6% are white females," the airline said in a statement.

"This means that only 15% of SAA pilots are black, ie Africans, Coloureds [mixed race people] and Indians. This emphasises the need for SAA to align this intervention to its transformation strategy."

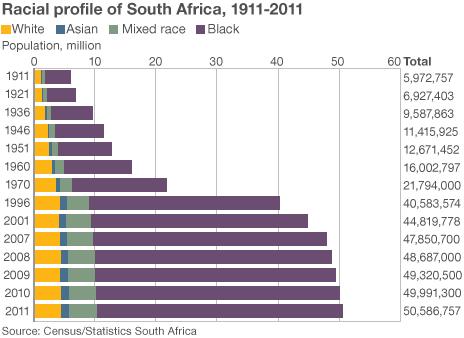

According to the 2011 census, whites make up 9.2% of South Africa's population.

Something is clearly wrong at SAA, and something clearly needs to be done.

Does it include a blanket ban of white candidates, though?

What should managers at SAA do to correct the clearly skewed employment patterns among its pilots?

'Cash cow'

Eighteen years after democracy, South Africa is still grappling with issues of race, representation, redress and equity.

A raft of laws ranging from affirmative action to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) have been adopted, but the debate is still as raw today as it was back in the early days of a new South Africa in the late 1990s.

Last week the secretary general of the governing African National Congress (ANC), Gwede Mantashe, received both plaudits and brickbats when he said black-owned companies, which receive preferential treatment in the dishing out of government contracts in line with BEE legislation, used the state as their cash cow by supplying sub-standard goods at abnormally large fees.

Mr Mantashe said most black-owned firms built public schools or supplied services at three times the normal price.

He and many others are of the view that for this and other reasons, BEE has not worked and has benefited only a small coterie of politically connected individuals.

While this coterie has become the reviled face of Black Economic Empowerment, the recent protests at Lonmin's Marikana mine have presented the face of poverty and inequality to South Africans yet again.

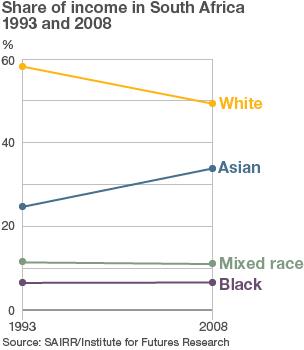

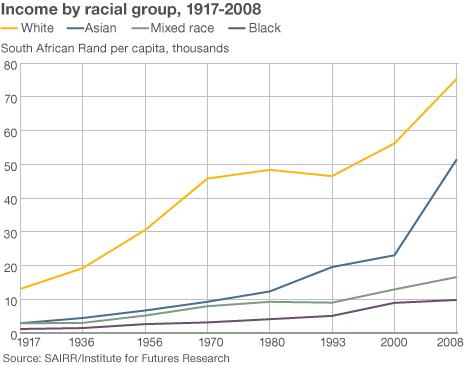

In its latest report on South Africa, the German think tank Bertelsmann Stiftung says: "Since democratisation in 1994, income inequalities within the different race groups, especially within the black population group have increased strongly.

"According to the latest figures from the World Bank, 42.9% of South Africans can be considered to be poor, with less than $2 [£1.25] a day to live on. The overwhelming majority of these are black South Africans."

Underclass

And there lies the rub.

We have lifted a massive amount of black people out of poverty and - crucially - removed the barriers to their being able to improve themselves.

Yet they are leaving behind another, huge and restless underclass.

Where should our emphasis be?

South Africa, with Brazil, are now the two most unequal societies in the world.

It would be easy to argue that efforts to empower blacks should be scrapped because, surely, after 18 years race does not matter any more.

Instead, inequality and class differences are the real divides.

When the poor rise up, they will rise up against the rich in general and not against the white rich only.

It is a seductive argument, often put up by South Africa's former President FW de Klerk and others in saying the ANC's policies have failed the poor.

As in the SAA case, the truth is a little bit more complicated and needs a far more nuanced approach.

South Africa's education system is letting down many teenagers

What South Africa now needs is a leadership crop that will commit to an economic programme that both grows South Africa's lethargic economy - we will only achieve 2.5% growth this year - to create the jobs we need to lift those languishing at the bottom of our society out of their desperate plight.

It remains a crime that seven million of our fellow citizens are unemployed and more than 2.2 million of them say they have given up looking.

Blanket ban?

The ANC has failed to provide such an economic programme and is mired in ideological battles and corruption.

Programmes to include blacks, if this economic programme is implemented, will increasingly become irrelevant.

For now, however, such programmes remain necessary and a nuanced programme at SAA - not the blanket ban of whites - is a case in point.

Such policies cannot be retained in perpetuity, and indeed a cut-off date may be necessary for them.

Does race or class matter - and which matters more?

Neither really matter right now. It is education that matters.

Our country is the worst performer in maths and science education in the world, according to the World Economic Forum.

Our government has failed to deliver textbooks to hundreds of thousands of children this year.

One in six pupils who wrote last year's matric secondary school-leaving certificate in maths got less than 10%.

We can bang on until we are blue in the face about getting blacks into positions of authority.

But we need to educate them to be able to fill those positions.

In this we are failing signally.

It is poverty, inequality and lack of education that will push our country to the brink now.

The explosion will come from these quarters.

It will not be race.

The programme BBC Africa Debate will be exploring race in South Africa in its next edition to be recorded and broadcast from Johannesburg on 31 August 2012.

- Published23 August 2012

- Published2 February 2011

- Published23 August 2012

- Published9 July 2024

- Published8 June 2013