Jose Eduardo dos Santos: Angola's shy president

- Published

In power for 33 years, despite having never been formally elected, Angola's President Jose Eduardo dos Santos is Africa's second-longest serving head of state - trailing Equatorial Guinea's Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo by just one month.

At home he has a firm grip on all aspects of government, is the head of the armed forces and responsible for appointing senior judges.

Overseas, as president of one of Africa's major oil producers he has positioned himself as a regional wise man, receiving weekly visits from various African leaders, and has developed strong links with China, as well as Brazil and the United States.

The 70 year old is never criticised by the country's state media organs, and the remaining few private newspapers that have not been bought up by government ministers and which dare challenge his actions are hit with lawsuits.

He is now hoping to win a new five-year mandate when his country holds parliamentary elections on Friday under a new constitution that elects the president from the top of the winning party list.

Analysts say the election is as much a referendum on Mr dos Santos, who celebrated his birthday on the campaign trail this week, and his record as president as it is about appointing a new National Assembly.

For many Angolans who have endured decades of war and disruption, the president is their one continuity, his face beaming out from T-shirts, posters and framed photographs that hang on walls across the country.

As well as steering his county from one-party Marxist rule into a liberalised free-market economy - now one of the fastest-growing in the world thanks to oil - he is hailed for ending Angola's 27-year civil conflict, albeit militarily, and for keeping the country at peace for the last decade.

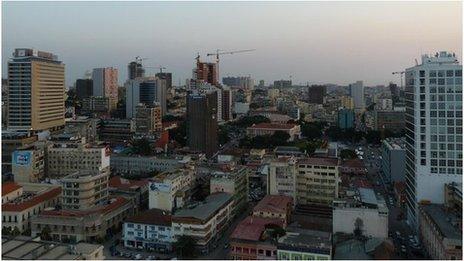

Under his leadership Angola has risen from the ashes of war to become sub-Saharan Africa's third-largest economy, after South Africa and Nigeria, and a magnet for foreign investment.

But while Mr dos Santos' long stay in office represents stability to his trading partners, one of the largest of which is now China, for some Angolans, particularly the younger generation, the president has outstayed his welcome.

Scripted speeches

In March 2011 a group of musicians inspired by the fall of the Tunisian and Egyptian presidents started a wave of street protests to call for Mr dos Santos to resign.

Wearing T-shirts emblazoned with "32 e muito" (32 years is a lot) the youngsters accused their president of being a dictator clinging unfairly to power and said not enough of the country's vast oil resources is being shared out among the people.

Their cause has been furthered by Angolan journalist and anti-corruption campaigner Rafael Marques de Morais who has published several reports alleging the involvement of members of Mr dos Santos' family and his close political circle have been involved in reportedly corrupt business deals.

Clearly rattled by the new wave of dissent against him, and events in North Africa, the president has hit back at his critics, publicly denying he is a dictator and explaining he too once lived in poverty and that he shares people's frustrations.

The 2012 election campaign has been focused on making Mr Dos Santos appear more appealing to younger Angolans, whom he has addressed directly at all his rallies, promising more university places and job opportunities.

His previously internet-phobic party, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), has launched a new website featuring campaign jingles and videos and it runs online media conferences.

The president has hit back at critics saying he too has experienced poverty

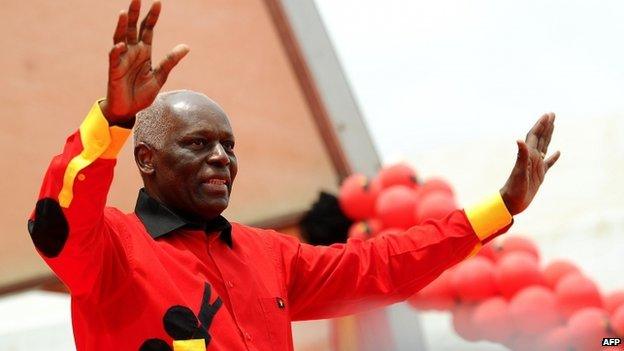

Gone are the president's stiff suits and silent public appearances. He is now more likely to be seen in a colourful shirt and baseball cap, offering plenty of bright smiles for the camera.

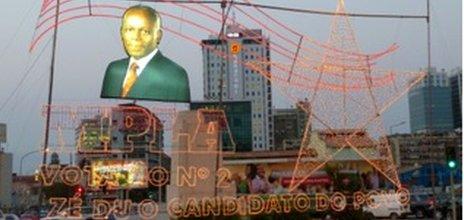

His party call him the "candidato do povo" - the people's candidate - and has used his nickname "Zedu" - a shortening of his first names Jose Eduardo - on posters and billboards which use soft colours to try and soften his appeal.

Nonetheless, unlike other political leaders photographed mingling with voters on the back of motorbikes, Mr dos Santos still travels with a large blue-light and military entourage that can shut down parts of the already congested capital Luanda for hours.

And while trips outside his luxurious pink palace are becoming more frequent, he always sticks to a scripted speech - and where possible shuns direct interaction with journalists.

Key to success

It has been more than five years since Mr dos Santos took part in a foreign media interview and he rarely attends regional summits of groups like the Southern African Development Community (Sadc) or the African Union (AU), sending ministers in his place.

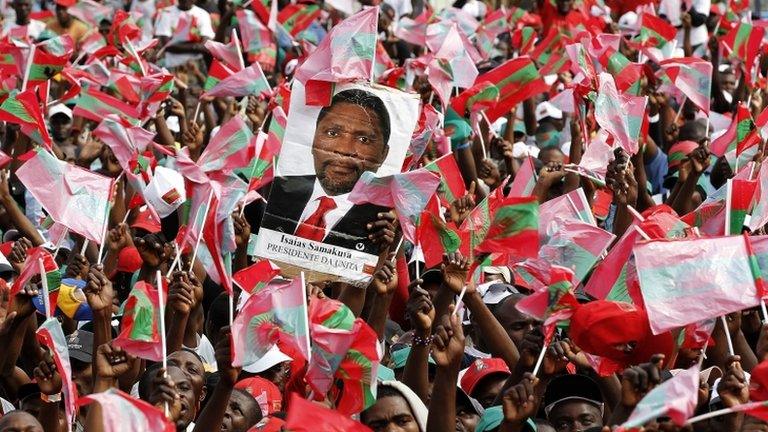

The MPLA has dominated politics since independence from Portugal in 1975

Analysts say Mr dos Santos' avoidance of the limelight is key to his success because has been able to keep his enemies guessing and he has carefully kept internal rivals at bay.

"Against all odds, he has remained in power since 1979, overcoming challenges of war, elections and at the same time displaying a highly refined political craftsmanship," said Alex Vines, director of Africa Studies at London think tank Chatham House.

Although not considered old for an African president, it is understood Mr dos Santos is looking for a way to step down in the not too distant future.

Earlier this year he appointed Manuel Vicente, his trusted friend and former boss of the state oil firm Sonangol, as minister of state for economic co-ordination and his vice-presidential candidate.

This sent the rumour mill into overdrive that the oilman could become Angola's next president.

"Mr dos Santos is starting to think about stepping down but he will want to ensure his political future is protected first," said Paula Roque, an Angola expert at the University of Oxford.

"He is fearful of being treated like the late Zambian President Frederick Chiluba, who stepped down from office and was then taken to court on corruption charges."

While criticism of Mr dos Santos is growing among small sections of urban Angolans, who are increasingly turning to the internet and social media as an alternative to the heavily censored mainstream media, he still plenty of support.

"I do agree our president has been in power for a long time, but if you think about it, we have only been at peace for 10 years so he's not had much chance to govern," said Henrique Pedro, 25, a bank worker from Luanda.

"For me, he is the best person and the most experienced."

Schoolteacher Manuel da Conceicao, 34, told the BBC: "I think the Angolan context is different. We have only had multi-party democracy since 1991 and we had a very long war after that... I don't think we really have the conditions for a change right now.

"What we definitely don't want is to see our president forced from power violently like how it happened in Libya or Egypt.

"When the time comes, we want a peaceful and dignified transition. Angola does not want any more war," she said.

Fond of music and football, the president is married to Ana Paula dos Santos, who is 18 years his junior, and has several children.

His eldest daughter Isabel dos Santos is regularly cited as one of the most influential businesswomen in Portugal, where she holds shares in energy, telecomms and financial companies.

- Published4 April 2012

- Published27 August 2012

- Published27 May 2011

- Published3 July 2012

- Published2 February 2012

- Published1 September 2011

- Published21 February 2023