Row over South Africa's role in CAR's rebellion

- Published

- comments

South Africa is quite an insular, self-contained nation. People here talk, without irony, about going to "Africa", when they venture into the vast, messy continent to the north.

That is not to say that South Africa does not involve itself in the affairs of Africa, or send troops on multi-national peacekeeping operations in places like Darfur in Sudan.

But it does so - at least in the minds of the public - at arm's length, and without any great sense of scrutiny.

But now this country has been genuinely stunned by the news that 13 of its soldiers were killed last month during a chaotic rebellion in the Central African Republic (CAR).

More to the point, people are starting to ask some unusually pointed, angry questions about exactly what those soldiers were doing in CAR and why they had not been pulled out when the security situation began to crumble.

The extraordinary allegation, spelled out here, external, is that far from taking part in a selfless training operation they were part of a murky business deal involving South Africa's governing African National Congress, and the now-toppled CAR President Francois Bozize.

"We are not used to seeing our soldiers coming home in body bags," said Nick Dawes, editor of the Mail and Guardian newspaper that is asking some of the toughest questions of the South African authorities.

"People are very disturbed. I think the government and ruling party are waking up to what a serious problem they've created - which is why there was such a hysterical reaction today."

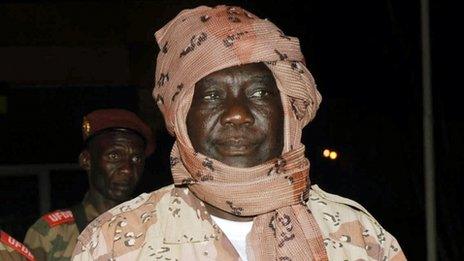

The rebels in CAR seized power just over a week ago

The "hysteria" Mr Dawes mentions refers both to the ANC's furious statement that his newspaper was "pissing on the graves" of South Africa's dead soldiers, external, and to President Jacob Zuma's indignant remarks given at a memorial service for the 13 men.

'Heroes'

It was hardly the occasion for a detailed rebuttal, and President Zuma did not offer one.

He insisted that the soldiers were "heroes", external who had died "for a worthy cause… promoting peace and stability" on the continent.

But Mr Zuma also went much further - explicitly questioning the right of journalists and others to probe the state on matters of security.

"The problem in South Africa is that everyone wants to run the country," he said, arguing that the ANC - with its hefty parliamentary majority - should be "given space to do its work".

Some will nod their heads at that. Others will find Mr Zuma's comments alarmingly self-serving.

And many will, surely, agree that the best way to honour the memory of those 13 dead soldiers is to make absolutely sure that South Africa finds out the truth about the military deployment in CAR.

Did South Africa's parliament - ANC and opposition - fail in its duty of oversight?

Have the distinctions between the government's duties and the narrower interests of the ANC become dangerously blurred?

Has the leadership of the South African armed forces become overtly politicised?

And did shady business deals in an isolated, unstable, mineral-rich African country (sounds familiar) lead to something that may one day be held up as South Africa's worst military scandal since the fall of apartheid?

- Published11 January 2014

- Published12 January 2013

- Published22 August 2023