Kenya's balancing act after Westgate attack

- Published

The Westgate crisis is the biggest security challenge yet to face President Kenyatta

Kenyan authorities face a delicate balancing act to limit social and economic fallout from the Westgate shopping mall attacks, while pressing ahead with military strikes on militants in Somalia, writes the BBC's Africa security correspondent Moses Rono.

Despite threats by Somali Islamists to carry out further attacks in the country, Kenya will not withdraw its troops from Somalia.

Islamists from the al-Shabab organisation, said to be affiliated to al-Qaeda, have claimed responsibility for the siege in Nairobi which left 72 dead - including five militants - and nearly 200 injured.

The crisis is the biggest security challenge yet to face President Uhuru Kenyatta, who inherited concerns linked to the spread of militant Islam when he took power in April this year.

It is bound to have wide-ranging social and financial ramifications for Kenya, East Africa's biggest economy.

The Westgate attack marks an escalation in attacks blamed on - and at times claimed by - al-Shabab.

More than 30 people have been killed in a string of bomb and grenade attacks that began after Kenya sent troops into Somalia to hunt them down in October 2011.

Kenyan authorities had accused the Islamists of a series of kidnappings inside Kenya, which threatened to negatively affect one of its major foreign exchange earners - tourism.

New scenarios

In the wake of what is seen as retribution by al-Shabab and their sympathisers across Kenya, security was increased in tower blocks in Nairobi, churches in the countryside and even on public transport.

But that did not last long - and as attacks decreased, so did vigilance.

By the time of the Westgate siege, security checks had become perfunctory.

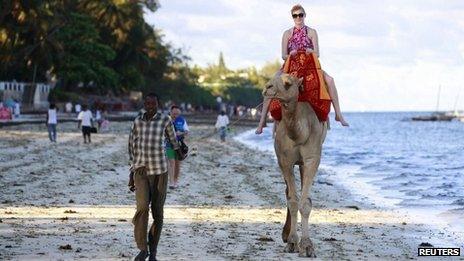

Kenya's safaris and beaches attract more than 1.8 million tourists annually

Some observers say that any serious attacker could easily bypass the random checks at the entrances of the shopping malls.

This is only now likely to change as Kenyan authorities scramble to deal with the consequences of the attack.

In the aftermath, a number of scenarios are starting to emerge.

The attack is likely to embolden Islamist and al-Shabab sympathisers to widen attacks, possibly even beyond Kenya.

"No doubt the al-Qaeda and al-Shabab types will try similar attacks, especially in the East Africa region," said Prof Korwa Adar, who teaches international relations at the United States International University (USIU) in Nairobi.

"Every country in the region should now take precautions."

'Safe for tourists'

It is believed that one of the reasons for the attacks is to stir anti-Somali and anti-Islam sentiment in the mainly Christian nation of Kenya, and possibly cause a backlash similar to one which led to violence in 2011.

Then there were concerted efforts by local leaders and religious groups to foster religious and social harmony.

In the wake of the Westgate siege, some Muslims and Somalis have come forward to denounce the attack.

They have been seen donating blood in tents set up for the drive.

President Kenyatta and opposition leader Raila Odinga jointly addressed the nation on Sunday in a show of unity.

"I call on Kenyans to stand courageous and united. Let us not sacrifice our values and dignity to appease cowards,'' Mr Kenyatta said.

"Let us continue to wage a relentless moral war," he said.

Mr Odinga asked Western governments not to issue travel advisories discouraging foreign visitors.

Tourism is one of Kenya's major foreign exchange earners. The country's safaris and sandy Indian Ocean beaches attract more than 1.8 million tourists annually.

The head of the Kenyan Tourism Board, Muriithi Ndegwa, said the fact that a major international conference on tourism got under way this week as planned showed the "resilience of the sector".

It also showed confidence in Kenya "as a safe destination" and that Westgate was an "isolated incident", he said.

Westgate Mall was part of Kenya's emerging commercial scene but further attacks could affect foreign investment, says East Africa analyst Aly-Khan Satchu

Meanwhile, an editorial in Kenya's Standard newspaper , externalhas warned that withdrawing Kenya's troops from Somalia would "embolden [al-Shabab] to stage more attacks".

Still, difficult questions about whether the country should rethink its security are now being asked.

A huge part of Kenya's security is handled by private contractors, which employ low-paid workers who have limited contact with the state security system.

Some members of the National Assembly have called for the overhaul of intelligence and immigration departments, blaming their laxity for allowing militants to enter the country.

Kenya and neighbouring Ethiopia are regarded as key allies of the West in the region, and are considered the major bulwarks in stopping the spread of terrorism.

Israel, the UK and the US have a long history of sharing intelligence and counter-terrorism information with Kenya.

That co-operation increased after the 1998 US embassy bombing in Nairobi, in which more than 200 people were killed.

Following the Westgate attack, these countries will have to review and improve this co-operation with Kenya's security service to deter terror attacks.

But a key question is how Kenya will now define what constitutes effective security.