Will Africa pull out of the ICC?

- Published

Victims of the violence in Kenya are still waiting for justice

With Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta under pressure to appear at the International Criminal Court next month to answer charges of crimes against humanity, the African Union (AU) has called a special summit to discuss Africa's relationship with the court. BBC Africa's Farouk Chothia reports.

The AU is heavily divided over the ICC, with East African leaders facing strong resistance from their West African counterparts in their campaign to whip up hostility towards the court.

Opposition towards the 11-year-old ICC runs deepest in East Africa - not surprising as two of the region's presidents - Sudan's Omar al-Bashir and Kenya's Uhuru Kenyatta - have been indicted, while Kenya's Deputy President William Ruto is already on trial on charges of crimes against humanity.

"There are strong passions around the issue. The ICC has been on the agenda of every AU summit since Mr Bashir's indictment," Steven Gruzd, an analyst with the South African Institute of International Affairs, told the BBC.

"The countries that are most vocal in their opposition to the ICC are in East Africa - Kenya, Sudan and Uganda. West African countries like Nigeria and Ghana are more supportive of the court," he said.

The AU has called an extraordinary summit, due to take place on Friday and Saturday, in an attempt to ratchet up pressure on the ICC ahead of Mr Kenyatta's trial next month.

Despite widespread speculation that the summit will consider calling on all 34 African members to pull out of the ICC, Kenya's Foreign Minister Amina Mohamed said on Wednesday that it was "quite naive" to think that leaders would "come together with the sole aim" of breaking ties with the court.

Mr Ruto's and Mr Kenyatta's trials are unprecedented - they are the first serving leaders to be tried by an international court.

Mr Ruto had to ask for his trial to be adjourned, so he could return home to deal with the recent Westgate shopping centre terror attack. He was given a week's delay - less than he had requested.

'Judicial coup'

"In advanced countries, sitting presidents are not hauled before courts. It's for the courts to wait for the president to finish their terms before proceedings can be instituted," Ms Mohamed told a news conference.

Like Mr Ruto, Mr Kenyatta is accused of organising violence after disputed elections in 2007, leaving some 1,100 people dead and 600,000 homeless.

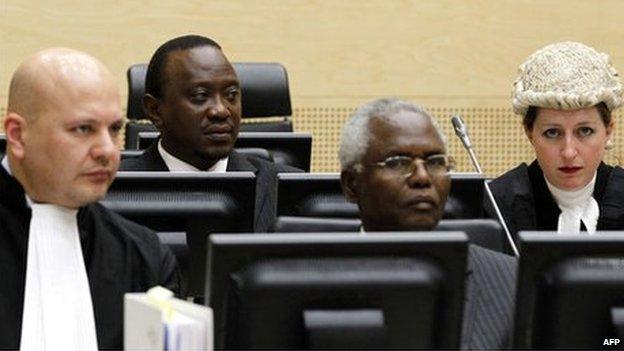

Uhuru Kenyatta (back row) had promised to co-operate with the court

Both deny the charges, and won in elections in March this year, with voters ignoring warnings by the US of "consequences" if they were propelled to power.

Mr Bashir, accused of genocide in Darfur, has refused to stand trial, as Sudan, unlike Kenya, does not recognise the ICC's jurisdiction.

His indictment in 2008 led to relations between the 54-member AU and the ICC plummeting, with the AU calling on countries to ignore an ICC arrest warrant for Mr Bashir, claiming that he enjoyed presidential immunity and that putting him on trial could jeopardise peace efforts in Darfur.

"The Kenyatta and Ruto trials have brought tensions to a head," London School of Economics researcher Mark Kersten, who set up the Justice in Conflict, external blog, told the BBC.

"The perception that the court is neo-colonialist and anti-African has burgeoned and solidified [in the AU]."

Significantly, South Africa, a major power-broker in the AU, which has been reticent to publicly criticise the ICC up to now, has joined the fray.

The governing African National Congress (ANC) accused the court of staging a "judicial coup" by insisting that Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto be present throughout their trials, rather than only at the initial and final stages.

"There is clear evidence that the ICC is used more to effect regime change in the majority of cases," it said.

'Bensouda rebuffed'

Though South Africa was a staunch advocate of the ICC's creation, its position is now closer to that of neighbouring Zimbabwe, which has always been a fierce opponent of the court.

"President Mugabe sees the court as a tool of imperialists. He believes that Tony Blair and George Bush should be in the dock for the war in Iraq," Mr Gruzd said.

"He is charismatic and dynamic and has clout in the AU. He can often change the game."

In contrast, only small southern African states such as Botswana, Lesotho and Mauritius are firm supporters of the ICC.

In North Africa, there is even less support for the ICC with only Tunisia recognising its jurisdiction.

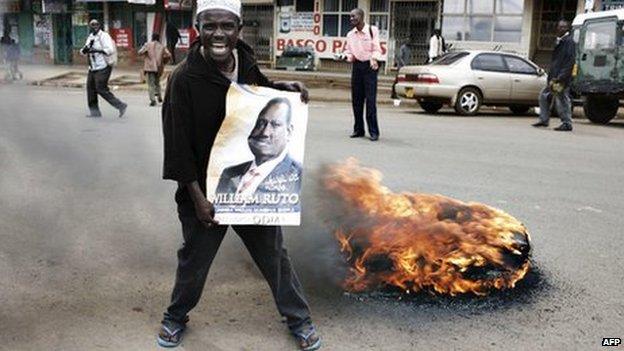

Former enemies, William Ruto and Uhuru Kenyatta teamed up for this year's election

But with the region in turmoil following the uprising against long-serving rulers, Mr Gruzd said he does not expect it to play an influential role at the summit.

Of the AU's 54 members, 34 have ratified the Rome Statute which established the ICC.

Significantly, the AU has failed to improve its relations with the ICC since the appointment of Gambian lawyer Fatou Bensouda as chief prosecutor last year.

This is despite the fact that it had lobbied for Ms Bensouda to become the ICC's first African chief prosecutor, succeeding Argentina's Louis Moreno Ocampo.

"The ICC made overtures to set up a liaison office in Addis Ababa, but it was rebuffed by the AU," Mr Guzd said.

One of the AU's main criticisms of the ICC is that it has only prosecuted Africans, suggesting that it is pursuing selective justice.

However, Mr Kersten pointed out that the ICC is carrying out investigations in other parts of the world, including Georgia and Colombia, although no-one has yet been charged there.

Charges have only been laid in eight countries - all in Africa: The Central African Republic; Democratic Republic of Congo; Ivory Coast; Kenya; Libya; Sudan and Uganda.

"In a lot of theses cases, the ICC intervened after referrals to it by governments," Mr Kersten said.

"It's not unusual for states to wear two masks, to engage with the ICC when it suits them and to criticise it when it doesn't. It's all very political."

A good example of this is Uganda, which asked the ICC to investigate the rebellion waged in the north by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) - a move that led to the court issuing an arrest warrant for the group's leader, Joseph Kony.

'Political machinations'

But at Mr Kenyatta's inauguration as Kenya's leader in April this year, Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni said he no longer supported the ICC because it was being used by "arrogant actors" who were trying to "install leaders of their choice in Africa and eliminate those they don't like".

In contrast, Ghana's President John Mahama has expressed strong support for the ICC.

In an interview, external with France 24 after the AU denounced the ICC for "hunting" Africans at a meeting in May, he said: "I will not go as far as accusing the ICC of racism... I think the ICC has done a fantastic job in bringing some people who have committed genocide and mass murder to justice."

However, Mr Kersten acknowledged that some of the AU's concerns were valid.

"It would be folly to deny the fact that the ICC works within an international structure that is far too unequal... This structure reinforces the reality that powerful states are too often shielded from accountability," he said, pointing out that three of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council - the US, China and Russia - do not recognise the ICC's jurisdiction over their territories.

"The court's promise was to transcend this by being an impartial institution independent of the realpolitik machinations of institutions like the UN Security Council and "great powers" like the US. It hasn't been able to do so," he said.

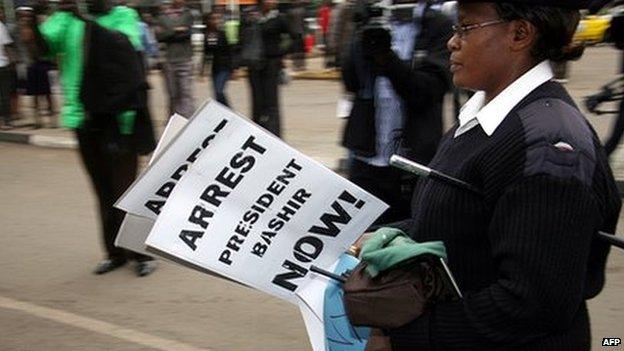

The AU has told African states to ignore the ICC's arrest warrant against Sudan's President Bashir

The UN Security Council has only referred conflicts in Africa - Libya and Darfur - to the ICC for investigation.

"The UN Security Council is very politicised and the ICC will have to think more critically about how its relationship with the body and the US are perceived by the rest of the world," Mr Kersten said.

"If its work is constantly politicised by major powers, the whole system of international justice will be weakened. That will be a price too high to pay."

Mr Gruzd said that while many African governments are hostile towards the ICC, their constituents are strong supporters of it.

"There is a fundamental divide between African leaders and African people," he said.

On Monday, about 130 non-governmental organisations wrote an open letter to the AU, warning that "any withdrawal from the ICC would send the wrong signal about Africa's commitment to protect and promote human rights and to reject impunity".

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan has also warned African leaders not to quit the ICC.

"If they fight the ICC, vote against the ICC, withdraw their cases, it will be a badge of shame for each and every one of them and for their countries if they do that," he said, when delivering the annual Desmond Tutu Peace Lecture in Cape Town on Monday.

Mr Kersten said that while Kenya's parliament has voted to withdraw from the ICC, he does not expect this to happen.

"It will require the head of state, who made a promise during the election campaign to co-operate with the ICC, to deposit a motion at the UN saying: 'We are withdrawing.' It's not a politically intelligent thing to do.

"Leaving the ICC is not a pressing issue in any other African state... It is more politically sensible to remain part of the ICC system and selectively endorse and criticize it from the inside," he said.

Hinting that this was Ghana's approach, Mr Mahama told France 24 that while he supported the ICC, he opposed its decision to try Mr Kenyatta, who was elected to office five years after the violence for which he has been called to account.

"What would you say - the verdict of the Kenyan people or the verdict of the ICC, which of them is more important?" he asked.

But international lawyers argue that the whole point of the ICC is to prevent national leaders from using the "shield" of immunity to escape prosecution for the atrocities which some have been accused of carrying out.

- Published10 September 2013

- Published5 December 2014

- Published27 May 2013

- Published12 December 2011

- Published7 February

- Published27 November 2017

- Published7 January 2015