I caught Ebola in Guinea and survived

- Published

The number of people who have contracted the Ebola virus in Guinea, according to the World Health Organization, has risen to 208 - and 136 of them have died. About half of these cases have been confirmed in a laboratory - earlier cases were not tested.

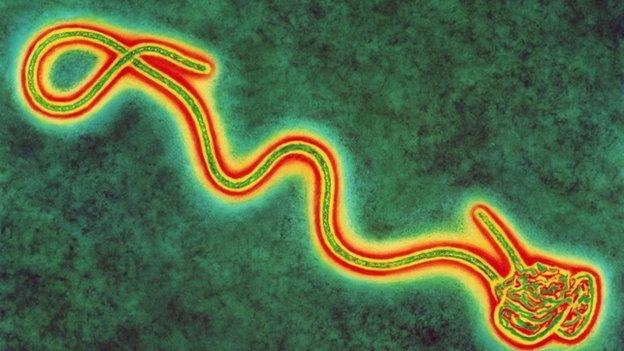

There is no cure for Ebola but with early medical support some people's bodies are able to develop antibodies to fight it off.

One survivor, who asked not to be named, told the BBC his story.

Testimony:

The symptoms started with headaches, diarrhoea, pains in my back and vomiting.

The first doctor I saw at a village health centre said it was malaria - it was only when I was brought to a special unit at the hospital in [the capital] Conakry that I was told I had the Ebola virus.

I felt really depressed - I had heard about Ebola so when the doctors told me, I was very scared.

I tried to be positive - I was thinking about death, but deep inside I thought my time had not come yet and I would get over it. That's how I overcame the pain and the fear.

Doctors from the charity Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) were here to comfort me and give their moral support. I tried to stay positive although I was scared when I saw my relatives dying in front of me.

There was a moment when I thought I might die when I lost two of my uncles and their bodies were taken away.

On that night none of us could sleep - we thought we would never make it to the morning.

Some doctors from MSF came to collect and wrap the bodies and sterilise the area. It all happened in front of us.

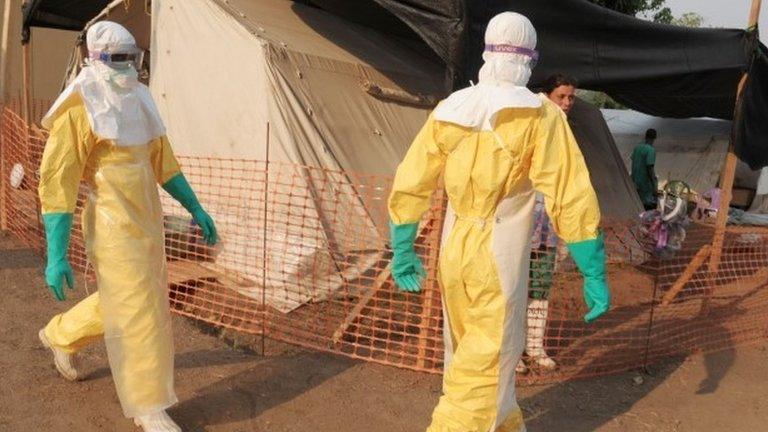

People moving the bodies of those killed by Ebola wear protective clothing

A short while after I was admitted to the hospital for treatment I started feeling better, step by step.

'Shook my hands'

At first I was scared to eat as I thought I would be sick but after a while I took a few drops of water and realised it was OK and the diarrhoea gradually stopped as well.

The doctors would come to see me and ask questions and one day nearly all my answers were "no" - the doctors were pleased and I realised that I would make it.

That was a very powerful feeling for me.

It was a great feeling when I walked out of the hospital.

We had a little celebration with the doctors, all the nurses and the people who had been waiting for me.

They took pictures of me, they shook my hands - I saw that they felt safe touching me and I realised I was better. I was really happy on that day. Now I feel good although I sometimes get some pain in my joints.

I prefer not be identified in the media - many people are aware that I had the disease but many others are not.

We have been through difficult times - people were afraid of us.

You know about African solidarity - usually when someone dies people visit you but when we lost one and then two, three, four members of our family, nobody came to visit us and we realised we were being kept at bay because of fear.

It gets even worse if everybody hears about your condition on the radio and television.

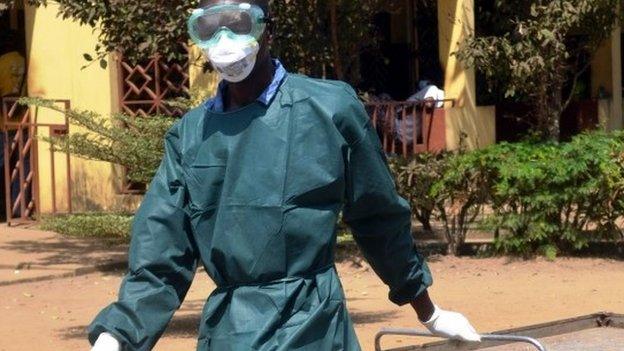

People in Guinea are poorly informed about the virus

Even people close to us, neighbours and relatives, are met with suspicion when they mention they know us.

Immediately the other person takes two or three steps back for fear of contracting the virus. People are very poorly informed about the disease.

Nine people in my family had the virus in total. My wife and my cousin survived too, so it is the three of us out of nine.

We were very affected by the deaths of our relatives but we were also relieved that not all of us had died.

It would have been such a catastrophe if we had all passed away.

This was a lesson on a spiritual level and it has changed the way I look at life.

The short time we spent in hospital has really transformed us. I feel lucky. I feel very happy to be alive.

This interview was featured on Newsday on the BBC World Service.

- Published14 May 2018

- Published3 April 2014

- Published8 October 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published6 December 2011