Nigeria's Boko Haram crisis reaches deadliest phase

- Published

Since the abduction of more than 200 schoolgirls two months ago and subsequent international promises of assistance to Nigeria, attacks by Islamist Boko Haram militants have been relentless.

This year has been without doubt the most violent stage of the conflict so far, with at least 3,300 people killed in Boko Haram-related violence since January.

And where the insurgents are operating they are killing, looting and torching entire villages often with little or no resistance.

"If government can't protect us, let them give us guns," one resident of a village near Chibok, from where the girls were abducted, told me.

Vigilante groups want to be properly armed to defend villages from attack

"We are sick and tired of running away every night," he said, adding that people were increasingly relying on traditional medicine for protection - performing rituals in a desperate hope of becoming what is known as "bulletproof".

Hit and occupy

Given the nature of a counter-insurgency, the military faces a huge challenge.

Boko Haram fighters can hide out and then converge to pick a target, easily outnumbering the defensive troops at that location.

"The army has to be everywhere; Boko Haram does not," says James Hall, a retired colonel and former UK military attache to Nigeria.

"The Nigerian military is outgunned because Boko Haram can concentrate its firepower on one place where the army is not present.

"They need a lot higher density of troops per square mile in the north-east than they have."

But there are also complaints of being totally let down by the military in the worst-affected areas.

Take Gwoza district in Borno state for example, where the militants have raised black-and-white jihadist flags in several villages.

On 1 June, they attacked a church in Attagara, killing nine people - but the villagers retaliated, killing many more militants.

Two days later, the insurgents returned to punish the entire village.

Attacks in Borno state have been relentless this year

Villages are now often targeted

After tricking people into thinking they were soldiers who had come to protect them, they opened fire - chasing those who fled on motorbikes.

Survivors hid in the nearby hills from where they could see billowing smoke as village after village came under attack.

They told the BBC that more than a week after the attacks started soldiers had not reached the area.

These were not hit-and-run attacks, they were hit and occupy.

It was too dangerous for men to go back to the village and young women risked abduction, so they sent elderly women to bury the dead.

"The women went around with their hoes and dug shallow graves where they found the corpses," a survivor said.

Neither the government nor the military said a word about the attacks until 6 June.

Who are Boko Haram?

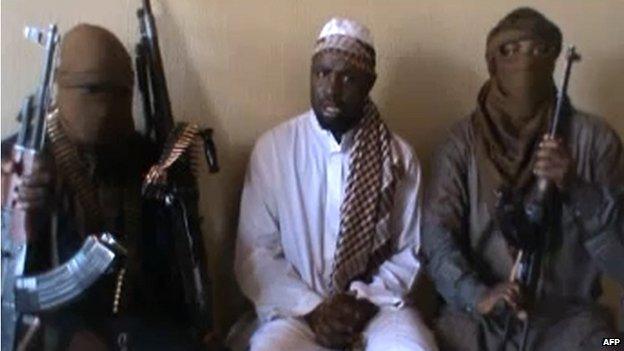

The militants are well-armed and often wear military uniforms

Founded in 2002

Initially focused on opposing Western education - Boko Haram means "Western education is forbidden" in the Hausa language

Launched military operations in 2009 to create Islamic state

Thousands killed, mostly in north-eastern Nigeria - but also attacks on police and UN headquarters in capital, Abuja

Some three million people affected

Declared terrorist group by US in 2013

It has also been suggested that soldiers have not had the equipment they need to fight this war, despite massive increases in the security budget in recent years.

In February, President Goodluck Jonathan was angered when the Borno state governor said Boko Haram was better equipped and motivated than the military.

Improvements to the military are needed

Last week, he seemed to be admitting there was a problem after all.

"I assure you that those issues of equipment and other things for the military, we're handling them," he was quoted as saying.

Recent international summits on Boko Haram have suited the Nigerian government.

Having been accused of playing down the gravity of the insurgency, President Jonathan has recently been referring to the group as "al-Qaeda in West Africa", in what some see as an effort to internationalise the issue and spread the blame.

Although Boko Haram is known to have had links to al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, it is still a very Nigerian problem, and to keep the north-east safe, improvements to the military are needed.

Exodus

But there is no quick fix, even with heavy reinforcements.

"Lack of communications equipment and mobility make rapid response extremely difficult," Mr Hall said.

"New equipment, new training and new people are all required - and that takes time."

The schoolgirl abductions put the insurgency in the world's spotlight but the incessant killings since then have not created anything like the same attention.

Politics matters

"The thing I've noticed is that conflicts, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, fade from the headlines pretty quickly," the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, told the BBC after a visit to Nigeria last week.

"Boko Haram are a group of the upmost evil. The militants are dealing out death right, left and centre without hesitation and without mercy."

The Nigerian authorities were heavily criticised after the abductions - not because the atrocity had been allowed to happen but because there was disbelief that it was hardly registering on the government's radar.

President Jonathan was being told that it was all a ploy by political opponents and rather than focusing on rescuing the girls, more energy seemed to be spent playing down the scale of the tragedy.

Many people in the north-east have left behind their lives in small settlements because they feel unprotected

Given that criticism, Archbishop Welby was asked whether he thought the government was now taking Boko Haram seriously.

"There is no question this is the dominant issue in the country at any moment with all the senior people you talk to or listen to," was his response.

But many Nigerians disagree.

There is an election in less than a year and everything is being seen through that prism.

If the primary focus of all the politicians was keeping people safe from Boko Haram attacks, the situation in the north-east would improve considerably.

But it is not and that is the tragedy.

As the killings continue, the political campaigning goes up another gear each month.