How is Ebola being treated on the ground?

- Published

As the death toll from the Ebola outbreak spirals and cases recorded outside its West African epicentre increase, concern is growing over the measures in place to contain the deadly virus.

But with the battle to tackle Ebola taking a heavy toll on the struggling health systems in affected countries, what is being done on the ground to treat those infected and stop the disease from spreading?

Here we show how an Ebola treatment facility run by medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) operates.

-

An Ebola treatment centre

× -

Entry point

×Anyone displaying symptoms pointing to an Ebola infection enters here to be examined by medical staff in protective gear. Patients are then split into two groups based on the probability that they have the virus, with their tests sent off to the laboratory for analysis.

-

Low probability ward

×Patients could face a long wait until their test results from the lab come back, revealing whether or not they are infected. Patients who might not have the deadly virus are isolated from those suffering from Ebola, reducing their exposure to the infection while in the treatment centre.

-

High probability ward

×Patients suspected of having Ebola based on the initial medical examination remain here until official confirmation arrives that they have the virus. Only once the Ebola diagnosis is confirmed are they transferred to another ward.

-

Ebola ward

×Patients whose blood tests confirm they are suffering from Ebola are placed in this ward. Medical workers are on hand to provide supportive care and treatment for symptoms like dehydration, but cannot do much else as there is no cure for the virus.

-

Decontamination

×When leaving the high risk area, referred to as the red zone, medical workers must ensure they decontaminate their equipment. In full kit, they walk through a decontamination shower which sprays a 0.5 per cent chlorine solution as well as stepping into a chlorine footbath.

-

Dressing rooms

×Dressing for a high risk area is a complex process. Medical workers work in pairs, with the partner checking for any tears in the suit. The protective equipment includes a surgical cap and hood, goggles, a medical mask, impermeable overalls, an apron, two sets of gloves and rubber boots. The donning process takes around 15 minutes. Staff work with a partner when removing the equipment as well, taking off the gloves and suit inside out, washing their hands after taking off each item of clothing. Equipment that can be used again are disinfected and left to dry, while other items are incinerated.

-

Entrance for sick patients

×This entrance is reserved for patients who are definitely infected with Ebola. In these cases they go directly to the ward for ebola patients without being subject to medical tests.

-

Visitors

×Patients who are strong enough can walk out of their wards and talk to any relatives and friends outside. The double separation makes touching impossible, eliminating the risk that visitors can become infected. Visitors are sprayed with a chlorine disinfectant solution.

-

Mortuary

×The fatality rate for this ebola outbreak is close to 50 per cent, so one in every two patients infected so far have died. The mortuary is located outside the clinic but within the double fence as bodies are highly infectious. The bodies are buried in nearby cemeteries located outside the treatment centre by staff wearing full protective gear.

-

Patient exit

×The exits on the side are for patients whose blood tests show that they do not have ebola, or those that recover. They take an antiseptic shower and receive a change of clothes before leaving the treatment centre.

The treatment centre is designed to separate confirmed Ebola patients from probable or likely cases.

Upon entry, patients are examined by medical staff in full protective gear.

Following the initial diagnosis, they are then split into low or high probability wards until the laboratory results come in, which could take anything from a few hours to days, depending on the facility.

There is little that medical workers can do for their patients, as there is no cure for Ebola. All they can help with is to care for the patients and treat symptoms like dehydration, as well as wash and comfort them.

According to MSF, good care increases the chances of survival from a disease that has a 50% fatality rate and whose symptoms include vomiting, diarrhoea and bleeding, sometimes from the eyes and mouth. However, overcrowded facilities and a shortage of staff on the ground have made this difficult so far.

Protecting medical staff

When coming into contact with patients, or entering areas where contamination risk is high, medical workers always put on special protective gear following strenuous procedures designed to ensure contagion risk is minimal.

The equipment includes waterproof overalls, gloves, medical face masks and goggles. All parts of the clothing must be completely impermeable since Ebola is spread in bodily fluids such as sweat, urine and blood.

Medical staff are advised to wear the equipment for no longer than an hour at a time due to the high temperatures that can build up in the suit, as the BBC's Danny Savage explains.

Health workers face increased risks in the battle to combat Ebola, with more than 400 contracting Ebola since the onset of the outbreak. More than half of those infected, 232, died from the virus.

In July, Dr Sheik Umar Khan, who was leading Sierra Leone's fight against the epidemic, died of Ebola. The first case of contagion outside West Africa involved a Spanish nurse who had treated Ebola patients who had contracted the virus in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

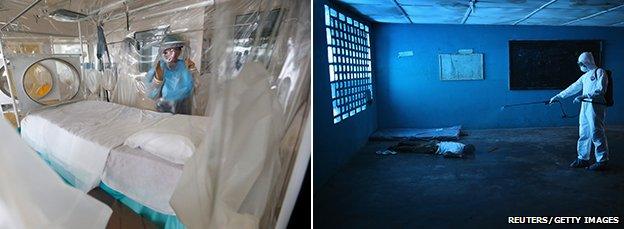

The contrast between conditions fighting Ebola in London (left) and Monrovia (right)

International response

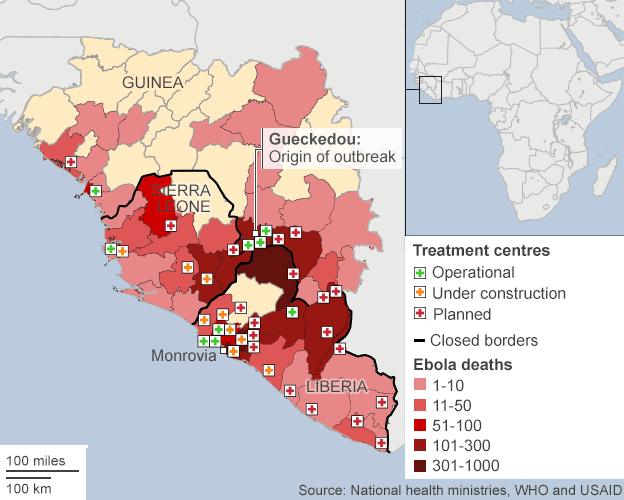

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has said that there is still a significant lack of beds in Sierra Leone and Liberia, with 3,000 needed - and the number is expected to rise.

With patients being turned away from treatment centres because of the lack of beds and space, additional treatment centres are desperately needed. The UK is sending 750 military personnel to Sierra Leone to help deal with the deadly Ebola outbreak. The United States has pledged to build 18 Ebola treatment centres, as well as sending up to 3,000 troops.

Brigadier General Stephen McMahon, of the UK Ebola Task Force, explains how an 80-bed treatment unit is being built in Sierra Leone.

Attempts to deploy more health workers and open new Ebola treatment centres in the worst-affected countries are gathering pace.

A group of 165 doctors, nurses and infection control specialists from Cuba arrived in Sierra Leone earlier this month and will spend six months helping local officials combat the epidemic.

The Cuban government will dispatch an additional 296 doctors and nurses to Liberia and Guinea after their training.

US and international treatment centres

Written and produced by Nassos Stylianou. Design by Mark Bryson.