Marikana massacre: Should police be charged with murder?

- Published

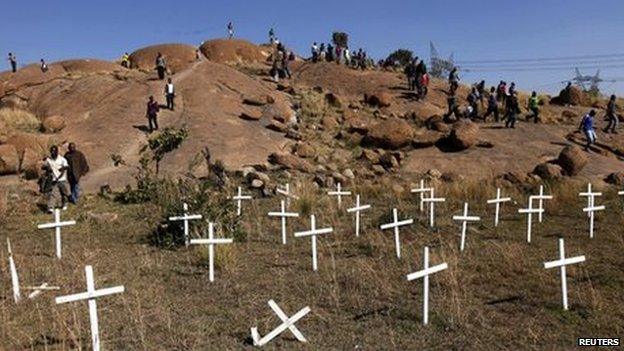

The Marikana massacre is the most deadly police action since the end of white minority rule in 1994

South African police have been accused of deliberately "operating as a firing squad" when they killed 34 striking workers at the Marikana platinum mine in 2012. The claim comes from lawyers working for the judge whose long inquiry into the shootings ends on Friday.

"This was a paramilitary operation, with the aim of annihilating those who were perceived as the enemy," say the evidence leaders - lawyers working alongside Judge Ian Farlam - in their written submission to the commission.

The allegations represent by far the most devastating critique of South Africa's police - who are also accused of lying systematically in their own evidence - given that they are being made by independent officials, not representatives of the miners or their families.

The Farlam Commission has spent almost 300 days hearing evidence about the 2012 killings. Judge Farlam is expected to issue his recommendations next year.

'Suspicious explanations'

One of South Africa's most respected lawyers has already demanded that the country's police commissioner and other senior officials be charged with murder for their roles in the killings.

Judge Ian Farlam (right) will release his findings next year

George Bizos, who once defended Nelson Mandela, told the BBC that "senior people that devised the plan, senior officers who gave the ok to do it, and also the people that did the shooting" should be put on trial for murder.

"The time has come for the blame to be identified and made public," said Mr Bizos, likening what he sees as stonewalling by the police to the behaviour of their apartheid-era counterparts.

South Africa's police have consistently argued that their officers fired on the striking miners in "self-defence."

But huge doubts have been cast on that version at the commission - with the police repeatedly accused of lying, evasion, and changing their story about the circumstances of the killings.

The commission will recommend who, if anyone, should stand trial for the Marikana killings

"We avoid pejoratives," said Mr Bizos, explaining why he wouldn't call the police liars. But their evidence "is contradicted by the facts. There are too many suspicious explanations. The facts speak for themselves".

The transcript of the commission's work runs to 39,000 pages.

There are reams of searing testimony from surviving miners and their families.

Humiliatingly for the police, some of the most pointed criticism of their behaviour comes from international policing experts - including one hired by the South African Police Service (SAPS) itself.

Colleagues and relatives of those who were killed want justice

Although it will be up to Judge Farlam to sift through the evidence and reach his own conclusions, here are some of the more incontestable findings that strike me as particularly significant.

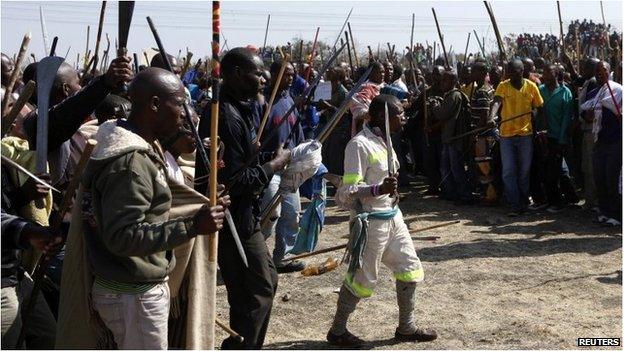

The miners were evidently retreating from the police at the time of the key confrontation (captured on multiple cameras and shown around the world) on 16th August. They were almost certainly seeking to escape back to their settlement, but found themselves boxed in by a row of police, by police vehicles, and by a nearby fence.

At least one of the miners fired a shot towards the police. But the police's response was manifestly out of all proportion. Many of the dead and wounded miners were shot in the head and back, indicating that no attempt was made to fire warning shots, or to "aim low" to minimise casualties, as required by law.

Subsequent written statements made by police involved at the scene were cursory, at best. Senior officials in the area claimed to be in the toilet, or lost, or facing the wrong direction, at crucial moments. In her evidence, National Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega struggled to remember anything about key conversations.

Rather than stopping to save lives and take stock (after one of the most devastating incidents in South Africa's democratic history), the police continued, almost immediately, to pursue fleeing miners, shooting dead 17 more, and subsequently - as their own photographs showed - planting weapons by their bodies.

That morning the police had brought in body bags, mortuary vans, and extra ammunition, clearly indicating that they planned a "decisive" end to an increasingly violent confrontation. A 40mm machine gun mounted on a police vehicle is surely meant for a war-zone, not an industrial dispute.

The police had lost their neutrality, becoming closely linked to Marikana's owners, Lonmin, to the extent that they passed messages from them to the miners and even shared a command-and-control centre at the mine.

The extent to which South Africa's government and influential ANC figures like Cyril Ramaphosa (now Deputy President - then a non-executive Lonmin director) are directly implicated in the bloodshed remains profoundly contentious, but unproven.

Disturbing scenes as police fire at miners in South Africa

"I've seen some cover-ups in my time, but never anything like this," said British lawyer James Nichol - who has been involved from the very beginning of the Marikana Commission, helping the team representing the families of the dead miners.

The South African police "have come out very, very badly. They fabricated evidence, they've fabricated videos police officers have come and told lies," he told the BBC.

"They've concealed a tremendous number of documents trying to cover their tracks for what happened on the 16th August,"

"Over 100 police officers fired lethal ammunition which killed 34 people. Only two of those officers were ever called to give evidence. It's quite astonishing," Mr Nichol continued.

Comparing the Marikana Commission to his experience in similarly high-profile British official enquiries, Mr Nichol said the truth would be heard.

"What we do know from the United Kingdom is that it took 40 years of Bloody Sunday to get truth. It has taken 25 years of Hillsborough to start to get the truth. I'm saying whatever happens here at Marikana, the truth will out at the end of the day."

The widows of the miners who were shot want the killers to be arrested and punished

The Marikana strike highlighted the poor salaries earned by miners around the country

It is clear that the government was putting pressure on the police to act aggressively to end the unrest, and by implication, the strike itself.

But no "smoking gun" text or email has been produced to show they sanctioned the killing of 34 miners in what was, evidently, a fluid and fast-moving incident.

Having said that, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the police had been given clearance at the highest levels to act with force.

As the police witness Cees De Rover put it: "I would be very surprised that SAPS would not have actively sought the guidance of the executive.

"The line of command doesn't stop at the National Commissioner. It goes right through to the top because the police are under government control."

I could go on. At a time when South Africa's trade unions are in great turmoil, the Marikana Commission has delved deeply into the relationship between unions and those they claim to represent.

It has examined the enduring iniquities of the migrant worker system that destroys families and disrupts communities.

And it has raised profound questions about the way power is wielded, and shared, by South Africa's overlapping elites.

But ultimately this is about the death of 34 men, 27 months ago.

South Africa is still waiting, with keen interest, to find out who - if anyone - will be put on trial.

- Published16 August 2013

- Published15 August 2013

- Published28 May 2014

- Published19 September 2012