A closer look at South Africa's racially charged debates

- Published

It has been a sour, tetchy start to 2015 here in South Africa. A string of social-media-fuelled debates about race and responsibility seem to have dominated the news agenda.

There was Nelson Mandela's former assistant's bitter claim that "white's are not wanted, external or needed in South Africa".

There were two prominent black female newspaper editors crossing swords over political bias and "the white internet, external".

And another columnist's work being branded "racist and mind-boggling, external".

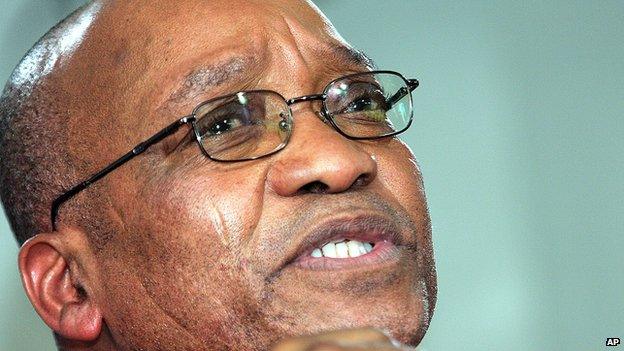

And then there was the governing African National Congress's not-entirely-welcome gathering in opposition-run Cape Town, external, where President Jacob Zuma leant back some 21 years into the past, to blame apartheid for South Africa's current electricity shortages, external.

Twitter storm

Zelda le Grange was Nelson Mandela's private secretary

At one level, it can all seem - and I know that as a white, privileged foreigner, I am treading on thin ice here - ever so slightly trivial.

On a continent - and in a country - facing such profound, complex challenges, the compulsive habit of so many here to define issues in terms of race and history seems like a gift to the government, which inevitably manages to steer the debate away from matters of more immediate accountability and substance.

Over the holiday period, I spent some time in a very different nation - to report on the 10th anniversary of the Asian tsunami - and was struck again by the optimism and energy of Indonesia.

Both countries have been through their share of trauma and chaos in recent decades, and both are still grappling with corruption and development.

But in Indonesia the focus and the debates seem resolutely, ambitiously, forward-looking, external.

Right v helpful

And yet, of course, here in South Africa, people have good reason to be preoccupied with their past.

You do not shrug off the legacy of decades of apartheid in one generation, and some white South Africans remain a little too snug in their cocoon of privilege.

"It's a mindset - it's like THEY enjoy chaos," said a white local to me a few weeks ago, peering contemptuously through the windscreen as we drove through a small traffic jam in an overwhelmingly black neighbourhood in the centre of Johannesburg.

But generalisations are dangerous. Or at least counter-productive.

As the years go by, some issues are slowly detaching themselves from the past. Soaring crime is rarely blamed on apartheid these days. Corruption, too, is increasingly tricky to link to history.

But many other problems - education, land reform, and inequality - remain much harder to unpick.

Then there is electricity.

President Jacob Zuma has been criticised for his response to South Africa's energy shortage

The governing ANC held its birthday celebrations in Cape Town in recent weeks

Many South Africans are suffering from rolling power cuts

Right now the power shortages facing South African homes and industry are acute and alarming, external, for an already struggling economy.

Eight years ago, President Zuma's predecessor, Thabo Mbeki, frankly acknowledged that his government had erred by ignoring industry's calls for investment in new power plants.

"Eskom was right and government was wrong," he said apologetically.

But earlier this month, President Zuma offered a different perspective.

"We don't feel guilty about the energy issue. It's not our problem of today, but a historic problem, one of apartheid, that we are resolving," he said, citing the apartheid government's attempts to undercut sanctions with cheap energy, and the ANC's ambitious plans to provide impoverished black families with electricity.

The debates over exactly how long one can keep blaming the past - on a range of issues - will grind on here.

But when it comes to electricity, the question, surely, is not so much whether President Zuma's analysis is right, but whether it is helpful.

- Published20 January 2015

- Published5 May 2014

- Published1 May 2014

- Published9 July 2024