South Africa: Has democracy delivered?

- Published

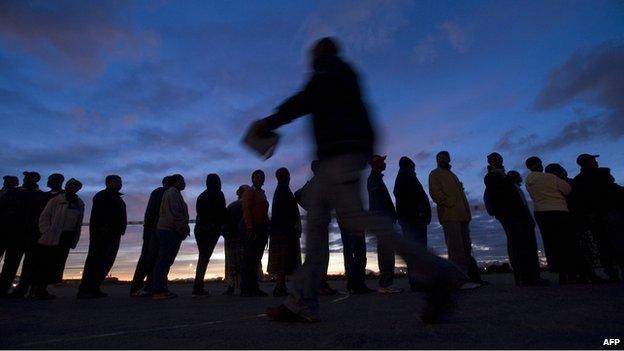

Although South Africa is in the throes of one of its worst political and economic crises since apartheid ended 20 years ago, the African National Congress (ANC) looks set to return to power after the 7 May elections.

Why will the ANC win again?

The ANC is showing signs of decay, but there is no-one to rival its dominance at a national level. The small and divided opposition has failed to capture the popular imagination, except in a few areas. South Africa's first black leader, the late Nelson Mandela, once predicted that the ANC would remain in power until around 2025 - and this is looking quite likely.

Liberation movements remained in power for decades in many African countries, as well as India, where Congress governed for 30 years after independence.

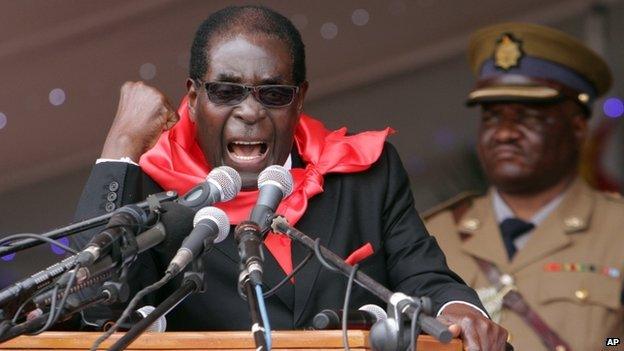

Could South Africa turn out like Zimbabwe?

Some have that fear, but the chances are that South Africa will be a messy but vibrant democracy, as the ANC has a long history of its members kicking out its leaders. South Africa also has a robust media and civil society, a feisty, if small, opposition, a powerful trade union movement and a strong business sector.

They are all trying to make sure the independence of democratic institutions is maintained. So far, the judiciary has played an admirable role in keeping a check on state power, along with the offices of the public protector and auditor-general.

However, other institutions, such as law enforcement agencies, have been accused of brutality, factionalism and corruption, raising fears that the distinction between party, state and business has become blurred.

The criminal underworld has also penetrated the state. One police chief - anti-apartheid struggle veteran Jackie Selebi - has been convicted of taking bribes from a drug dealer; another, Bheki Cele, was dismissed after an investigation found that police buildings had been leased at inflated prices from a private firm, though he was not accused of criminal behaviour.

Why is the opposition so small?

Led by Helen Zille, the Democratic Alliance (DA) is the ANC's main challenger. It was once a staunch admirer of the British Conservative party and the late Margaret Thatcher, but it now sees itself as similar to the Liberal Democrats.

It has never appealed to South Africa's black voters, who largely see it as a defender of the privileges white people gained during apartheid. As a result, it won only 17% of the vote in the 2009 election, but is expected to increase this to 23% in the 7 May election, according to a recent poll conducted by Ipsos.

Is the DA trying to change?

In an attempt to broaden its appeal, it has toned down its opposition to affirmative action - an ANC policy which most black professionals and businessmen welcome to help overcome the effects of the racial discrimination they faced during apartheid. In the last election, many of these so-called "black diamonds" cast their ballots for the Congress of the People (Cope), formed by an ANC breakaway faction opposed to the uneducated Jacob Zuma's ascent to the presidency.

20 years of social change in S Africa

But they feel let down by Cope, which has been hit by leadership battles and legal disputes. The DA is hoping its new young black leaders - especially in Gauteng, South Africa's richest province - will persuade them to vote for the party this time around, but other parties are also confident of gaining their support.

The DA has also tried to show it is a "struggle party" by marching on the headquarters of the ANC to demand jobs for the unemployed but, as the poll shows, it still has a long way to go to win the confidence of the black majority.

Where do other racial groups stand?

Like many white people, most Indian and coloured (mixed-race) South Africans tend to be fearful of ANC rule. Even Mr Mandela battled to win their votes, despite his image as a nation-builder. An opinion poll published about three weeks before the election gave the DA 78% of the Indian vote and 72% of the coloured vote.

The DA controls one of South Africa's nine provinces, Western Cape, where people of mixed race are in the majority. It is expected to retain control of the province, and fight ANC plans to introduce a new affirmative action policy that would require top managements posts in the business sector to reflect national, rather than provincial, demographics.

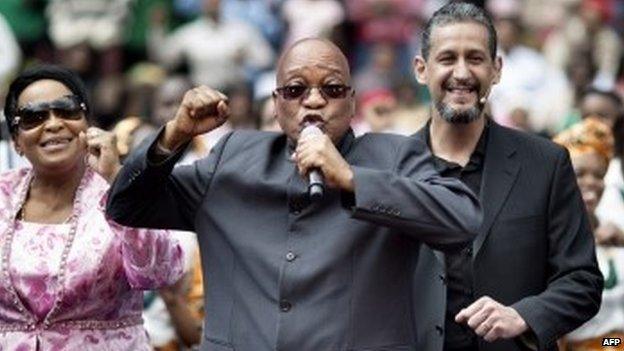

What are voter perceptions of Mr Zuma?

Of the four presidents South Africa has had since it became a democracy in 1994, he has the least moral authority.

"No-one believes anything he says," says Johannesburg-based political analyst William Gumede.

Corruption allegations have swirled around him for many years and these were strengthened with Public Protector Thuli Madonsela's finding that $23m (£13.8m) of taxpayers money was spent on upgrading his private rural residence - including building a chicken run, cattle enclosure, amphitheatre and a swimming pool.

Some believe the rot set in during the Mandela presidency, when he showed unflinchingly loyalty to then Health Minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma despite calls for her resignation after the public protector found her department had awarded a contract improperly to the minister's friend.

So will voters punish Mr Zuma?

Some analysts believe the ANC's majority will fall to a historic low of between 55% and 60%, and it could lose overall control of Gauteng, which includes Johannesburg and the capital, Pretoria, and would be a clear sign that the party is in decay.

But an opinion poll conducted after Ms Madonsela's findings were released gave the party 65% of the national vote - close to the 66% it obtained in 2009.

The ANC won in 2009 despite the fact that Mr Zuma was accused of taking bribes from a businessman and a defence company - an allegation he denied. He escaped being put on trial after prosecuting authorities dropped the charges, citing political interference in the case by an ANC faction opposed to him.

Mr Gumede says the ANC's biggest electoral advantage is that about 16 million South Africans out of a population of nearly 52 million receive welfare grants, such as child income support for single mothers, to cushion the effects of poverty. This block of voters guarantees the ANC 45% to 50%, as they would not put their grants at risk by defecting to the centre-right DA, he says.

What is the ANC record on other issues?

Seeing unemployment as an "assault on human dignity", Mr Mandela led the ANC's first election campaign in 1994 under the slogan: "Vote for jobs, peace and freedom". But his government and its successors have battled to fulfil the first part of this promise, with the official unemployment rate standing at around 24% at the end of 2013.

It is the ANC's biggest Achilles Heel, and could cause an uprising.

As Mr Mandela's successor Thabo Mbeki once warned: "When the poor rise they will rise against us all."

Protests, often violent, by people calling for more basic services such as water, housing and schools occur on an almost daily basis.

The story is more positive regarding health - the Zuma government has ended the Aids denialism of Mr Mbeki, and is giving free life-saving anti-retroviral treatment to patients.

It is also pressing ahead with its plan to create a National Health Service, despite strong resistance from the private health industry, fuelling perceptions that its main focus is on creating a welfare state.

Lebo Diseko asks if South Africa has kept the promises laid out in the Freedom Charter

Is Julius Malema a big player?

With his supporters saying he has charisma similar to that of the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, Mr Malema has styled himself as a revolutionary, wearing a red beret and carrying the title commander-in-chief of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party as he campaigns for votes.

He strikes the most fear among white people, with his calls for the partial nationalisation of the mining and farming sectors, and his support for Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe.

But after a poorly organised campaign, he seems to have taken very little support, with the Ipsos poll giving the EFF only 4% of the vote, less than the 5% the DA got among black voters.

Five other black-led parties polled less than 3%, and AgangSA, launched by businesswoman Mamphela Ramphele in January, did not register in the survey.

What are the battles ahead?

The chances are that the opposition will fragment even further, with the biggest union, the National Union of Metalworkers' of South Africa, planning to launch a left-wing party to contest the 2019 election.

Its general-secretary, Irvin Jim, has said that "non-racialism" is not working in South Africa, with many white people not identifying with the poor black majority. He also accuses the ANC of betraying the ideals of the liberation struggle by failing to promote socialism.

It is a sign of the battles that lie ahead between the ANC, DA and their left-wing opponents.