Boko Haram crisis: How have Nigeria's militants become so strong?

- Published

Nigeria's militant Islamist group Boko Haram is waging the most brutal insurgency in Africa. It has seized vast amounts of territory, threatening Nigeria's territorial integrity and opening a new frontier by targeting neighbouring Cameroon.

Officials estimate that some three million people are affected by the humanitarian crisis caused by the five-year insurgency in the north-east.

Why are the militants so lethal?

The group is said to be split into numerous factions, which operate largely autonomously across northern and central Nigeria.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) think-tank estimates there are six of them - the most organised and ruthless one is in Borno state, where Boko Haram has captured large swathes of territory.

It first sends hundreds of foot-soldiers into a town or village. Often overwhelmed due to inadequate supplies, the Nigerian army flees, paving the way for elite militant fighters to enter and conquer the territory.

This is a remarkable change in its fortunes. Soon after Boko Haram launched its insurrection in 2009, Nigeria's security forces declared victory over the group after killing thousands of its members - including its founder - during an operation in the city of Maiduguri.

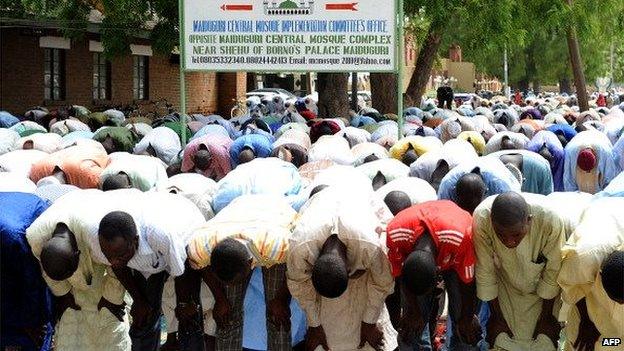

Some survivors fled to Algeria, Somalia - and possibly Afghanistan - for military training. Today the group is increasingly brutal in its modus operandi, losing the support, some analysts say, of many local Muslims who once saw it as offering an alternative to the corrupt ruling elite.

How does it recruit fighters?

Increasingly through conscription - villagers are forced to join en masse or risk being slaughtered. It is also relying on criminals and thugs, "paying them for attacks, sometimes with a share of the spoils", according to the ICG.

With ethnic loyalties strong in Nigeria, most Boko Haram fighters are Kanuri - the ethnic group to which the group's leader Abubuakar Shekau belongs - suggesting that he has influence over some traditional rulers in north-eastern Nigeria.

While it is unclear how many fighters Boko Haram has, UK-based finance and security analyst Tom Keatinge puts the number at more than 9,000.

Where does it get its money from?

When Boko Haram raids towns, it often loots banks. In 2012, the Nigerian military accused Boko Haram of extorting money from businessmen, politicians and government officials, and threatening them with abduction if they fail to pay up.

Some US officials estimate that the group is paid as much as $1m (£660,000) for the release of a wealthy Nigerian, Mr Keatinge says.

With foreigners, the amount is much higher - Boko Haram was paid $3m ransom for the release of a French family of seven seized in northern Cameroon in February 2013, according to a Nigerian government document seen by Reuters news agency at the time.

With these sources of funding, Mr Keatinge estimates that Boko Haram's annual net income is $10m. Nigerian researcher Kyari Mohammed believes the group is running a low-cost insurgency, as it is made up mostly of young people from rural areas.

How does it arm itself?

Boko Haram has overrun many police stations and military bases in Nigeria, giving it a huge arsenal - including armoured personnel carriers, pickup trucks, rocket-propelled grenades and assault rifles. And, according to the ICG, it has forged ties with arms smugglers in the lawless parts of the vast Sahel region.

Some of its weapons are suspected to have come from Libya, where arms depots were looted when Colonel Muammar Gaddafi's regime was overthrown in 2011.

However, most of Boko Haram's bombs are relatively crude, made from local materials that are easy and cheap to obtain, the ICG says.

Some of its bomb-makers, according to Nigeria-based security analyst Bawa Abdullahi Wase, are local university graduates who joined the group in desperation, after failing to find jobs.

And it has recently raided cement factories, including one owned by the French company Lafarge, in search of dynamite for its explosive devices.

Can it be defeated?

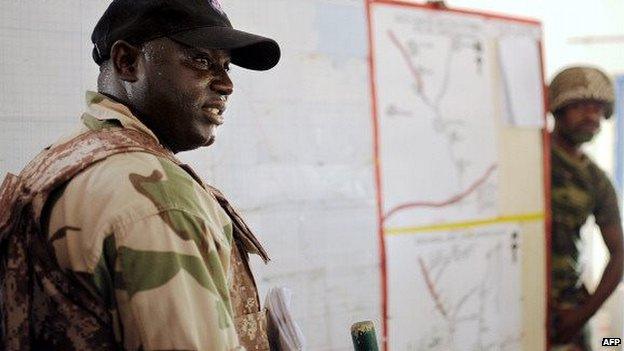

The government declared a state of emergency in 2013 in the three north-eastern states worst-affected by the insurgency. The military also armed vigilante groups, vital in remote areas where the military presence is minimal.

Boko Haram was driven from Maiduguri and neighbouring villages and into the vast Sambisa forest along the border with Cameroon. But the sect responded with a new offensive in which - according to the Associated Press news agency - it has taken control of an area about the size of Belgium.

Three states are under a state of emergency

If Boko Haram succeeds in its territorial ambitions - seizing towns in Niger, Chad and Cameroon, as its leader has threatened - the conflict could take on a new international dimension. France is likely to become more directly involved in the conflict to protect its former colonies.

So far Cameroon has been relatively successful in repelling Boko attacks, despite having a far smaller army than Nigeria, which has been criticised for not pulling its weight.

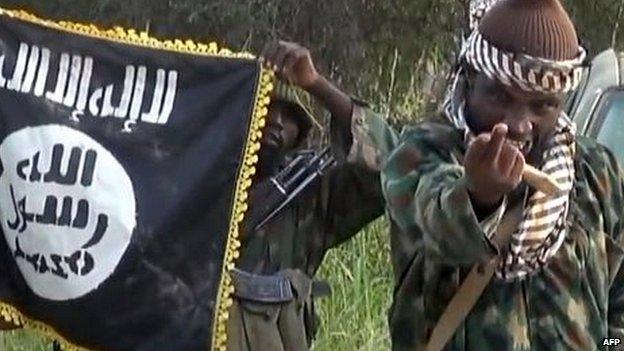

Is Boko Haram linked to IS?

Mr Shekau praised Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in a video released last year, referring to him as "Oh caliph". He has also praised al-Qaeda's Ayman al-Zawahiri, the IS leader's rival for the loyalty of worldwide jihadists. However, Shekau has not pledged allegiance to either group.

While he often speaks in a mix of Hausa, Arabic and Kanuri, his most recent video - where he praised the Paris attacks - was entirely in Arabic, leading analysts to suggest the Nigerian sect is seeking international appeal.

Solid ties with global jihadi groups would give further momentum to Boko Haram's violent campaign.