Eugene de Kock parole: Has justice been done in South Africa?

- Published

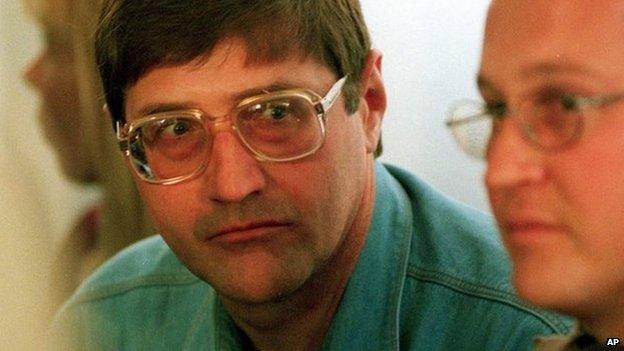

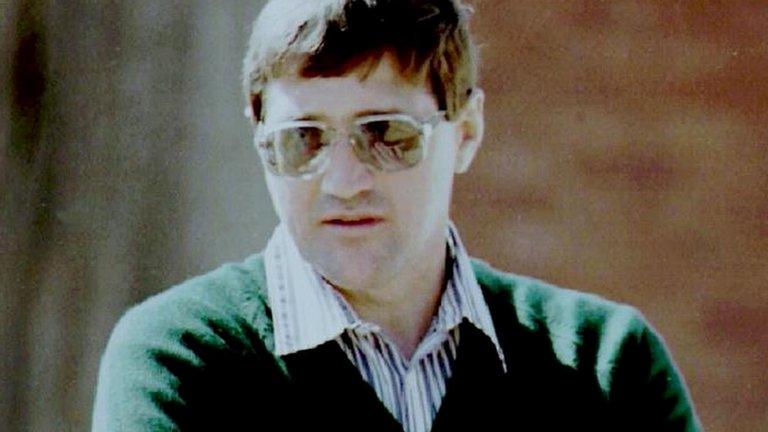

Former police colonel Eugene de Kock was in charge of the notorious Vlakplaas police unit

It is not easy to find Vlakplaas - the small farm where some of South Africa's most notorious apartheid-era murders took place.

On a dirt road about 20km (12 miles) west of the capital, Pretoria, I pulled over and waved down a passing pickup truck to ask for directions.

"Vlakplaas? Sure - it's just before the river, on the left," said a bearded white farmer. "But there were no murders there."

It was an early reminder that some white South Africans have yet to acknowledge the crimes carried out by their old government, and by one particularly notorious policeman - Eugene de Kock.

De Kock was in charge of a death squad that operated out of Vlakplaas, and was responsible for the abduction, torture, and murder of dozens of black activists in what would turn out to be the dying days of the apartheid era.

'Scary at night'

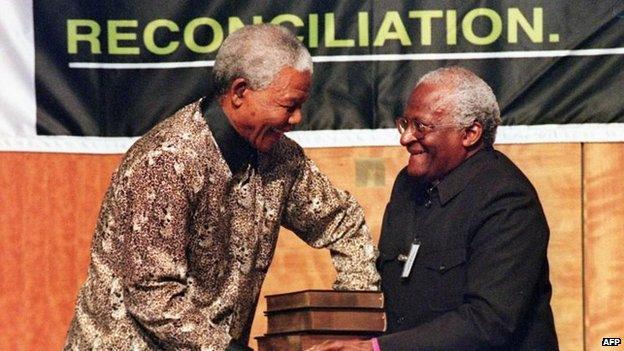

After the advent of democracy, De Kock confessed to many of his crimes at South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

But although he was granted amnesty for some offences, the courts concluded that his behaviour warranted two life sentences and an additional 212 years in prison.

"If they didn't burn them, then they shot them. If they didn't shoot them, they hanged them on that tree. And if they didn't hang them, they threw them in a pit and put dirt on them," said Morris Hlongwane, who helps to guard the Vlakplaas farm these days.

It is an eerily overgrown place, and "scary at night," said Mr Hlongwane, pointing to some bones he said were human.

I told him what the white farmer had said about "no murders" and he laughed and shrugged.

So should Eugene De Kock be released from prison now? I asked him.

"Um.... yes. He has to be released. We have reconciliation. We have to reconcile and forgive him," he said.

The TRC was set up by Nelson Mandela and chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu (R)

What about the others - the bosses who gave the orders and never faced justice?

"That's the problem. That's the problem. He was not alone."

A few days earlier, I had asked the same question of Sandra Mama.

In 1992 she had been newly married to an anti-apartheid activist named Glenack Mama, when he was gunned down by De Kock and had weapons planted by his body.

Nelson Mandela had already been released from jail and black-majority power seemed inevitable.

De Kock's unit was busy trying to undermine that process.

Forgiveness

"One man is taking the fall. Eugene didn't just wake up and think 'I'm going to do all this.' The others got away with it. South Africa as a nation has still got a long way to go," said Ms Mama.

But in September last year, as part of the parole process, De Kock began reaching out to some of his victims' families.

Ms Mama's husband activist Glenack Mama was killed by De Kock in 1992

A photo shows the tall prisoner, in his orange uniform, flanked by Sandra Mama and her children.

"This guy has done things that boggle the mind. I was face to face with this killer. It was so dark. [But] when he said sorry you could really see that he was genuine. I really believe he reached out because he wants to help, not just because he wants parole," said Mrs Mama.

"Eugene is just a product of the state. He's taken a fall for his government."

Mrs Mama's daughter, Candace, said: "He was stoic. Very controlled. But he has a dry, sarcastic sense of humour."

She asked De Kock if he had forgiven himself.

"He dabbed his eyes and looked down, then he looked me in the eye and said, 'When you've done what I've done how do you forgive yourself.'"

Partly because of those family encounters, as well as his co-operation with investigators still searching for the remains of other apartheid-era murders, De Kock was granted parole on Friday.

He will be released quietly, away from the cameras, and is expected to continue to help investigators.

'Scapegoat'

But what about De Kock's superiors?

"Who else do you see in prison?" asked Yasmin Sooka in frustration.

She was a senior official at the TRC, but regrets the lack of any subsequent investigations of prosecutions.

Eugene de Kock at glance:

Commander of Vlakplass police unit from 1983

Confessed to hundreds of murders at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Nicknamed "Prime Evil" for the death-squad revelations

Sentenced to 212 years and two life terms in 1996

In 2012, Marcia Khoza publicly forgave him for killing her mother ANC activist Portia Shabangu

Served 20 years before getting parole

"You cannot have one person in prison being held accountable for a whole state," she said, arguing that the decision to make De Kock a "scapegoat" had to have been an orchestrated policy.

"The big problem with South Africa is denial. And denial particularly by white society. For most white people in our country, the 'Mandela moment' was what they all enjoyed because it rehabilitated them in terms of the international community. But how many of them have paid voluntarily into a reparations fund?" she asked.

In the giant Avalon cemetery on the edge of Soweto, Bheki Mlangeni's mother and brother tended his grave and sang a short struggle song as the rain clouds moved in.

Mr Mlangeni was a human rights lawyer killed by one of De Kock's letter bombs in 1991.

"I don't feel that justice has been done," his brother Lindani Mlangeni said.

"At least 50 years - yes he deserves that. They call him a killing machine. How can he be afraid of dying in prison? The ones who gave the orders must also go to prison, or they must at least tell their story. Maybe there will be reconciliation at the top. But what about the victims?" asked Mr Mlangeni.

- Published30 January 2015

- Published30 January 2015