Breaking the stigma around mental illness in Uganda

- Published

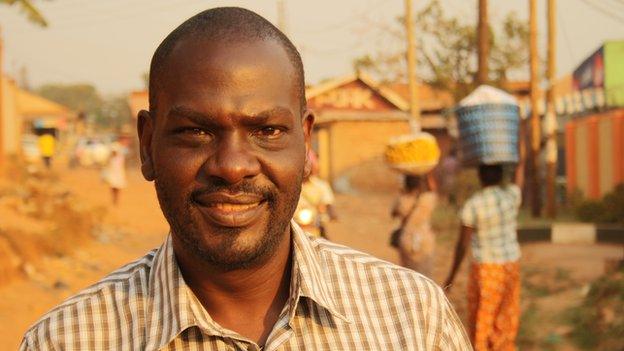

Joseph Atukunda has spent much of his life campaigning for a better understanding of mental health

In Uganda the stigma around people with mental disorders means when things go wrong they often have no safety net. Now some of them are starting to break the silence about their lives and changing the way people look at them.

Joseph Atukunda has had quite a life, not all of it happy.

Twenty-seven years ago he was standing in a field just outside his home town of Kampala, ready to kill himself. He felt like he'd lost a battle with deep depression.

Clutching a bag with a rope and rat poison in it, he was determined to end things. But something changed in his mind at the last minute.

"I got like a vision. I don't know whether from Jesus, Krishna, Muhammad or the Buddha telling me that you can still seek help."

Joseph would come to find out that he was living with Bipolar Affective Disorder. It causes him to have severe mood swings, moving between elation and despair. They can last for weeks or months.

But getting help was no easy task.

There are 30 psychiatrists working in Uganda. With a total population of more than 35 million people, that's less than one per million. The World Health Organisation estimates that 90% of mentally ill people here never get treatment.

But Joseph got lucky. He was admitted to the country's only psychiatric hospital: Butabika. There are six psychiatrists there, who look after hundreds of patients with severe mental disorders.

Patients at Butabika wear green uniforms to help the staff identify them on the campus

It can be a tough place. During manic episodes, Joseph could become violent, and he would sometimes be put into isolation. "One time I was stripped naked, given medication… I woke up at night, it was dark, I had a hallucination, I thought I had died and I was in hell."

Joseph thinks the hospital has come a long way since he was first admitted there.

But he would like them to be less reliant on medication. "I don't like to take medication every day because it reminds me that I am sick, and I don't want that mind-set".

The psychiatrists say they are over-stretched and have issues with overcrowding, but provide a the best basic service they can.

Patients help out with basic jobs at Butabika Hospital

Joseph thinks one of the biggest problems for people with a mental illness is that the disorders are not well understood. "It really can be a mystery, sometimes even the psychiatrists don't understand what's going on," he says.

The psychiatrists at Butabika estimate that 90% of Ugandans believe that mental illness is linked to curses or demons.

And Joseph himself didn't discount that possibility. He spent time at a traditional healer's clinic run by a man called Dr Hassan Serwadda.

Dr Serwadda was clear in his diagnosis: there was witchcraft involved. "Some demons were on your head" he tells Joseph, "so I cut your head to put the medicine in it, I slaughtered a cock and bathed you in blood."

For Joseph it was a difficult period, but he thinks the healer may have saved his life, and that tradition could have a wider role to play in mental health care.

"I was treated in this spiritual healer's crude structures, but I am well now" he says. "Even conventional medicine has its advantages and disadvantages. So I can't quite discard this spiritual healer as somebody who didn't contribute at all to the wellness that I'm enjoying right now."

Joseph Atukunda discusses traditional medicine with his former healer.

Apart from getting medical help, Joseph and some of his friends who also live with mental disorders think their larger problem is the stigma they face.

"Locally people say Mulalu, which literally means you're mad, you're useless" says Jimmy Odoki, who also has bipolar disorder. "Where I come from people say 'that one he's a walking dead'."

He and Joseph are relaxing by a pool in Kampala where the owner has given Joseph a free swimming pass so he can do the exercise he needs to help clear his mind.

"For me when I am walking along the street at home, there are some people who see me coming and they branch off," says Joseph, "they just fear completely without any compromise.... but I'm not blaming them!"

Away from Kampala, that fear means people with mental illnesses can end up being abandoned. One of Joseph's friends was taken in by a pastor who looked after the sick.

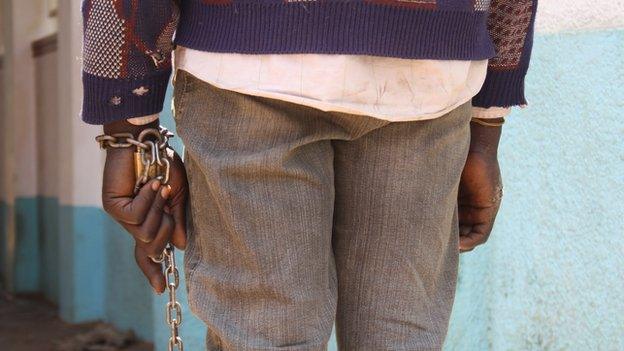

"He'd chain up his patients until his prayers had an affect" says Maureen Ainembabazi, who has schizophrenia. "I had to run away."

Some people with mental disorders are kept in chains at Glory Sinai Ministries in Seguku, Kampala

Joseph has worked hard to break the silence around his illness. He and fellow mental health patients have set up a support group they call Heartsounds. They work in partnership with Butabika Hospital to help former patients get support.

They try to meet regularly, sometimes at Joseph's home in Kampala.

"Peer support is very, very important," he says "and it is something that should be given a lot of attention, whereby the patients themselves support each other because we are experts by experience."

"I think I have even relapsed in the presence of many of you," says his friend Rashid Male, another who has bipolar disorder. "You see how I become when I relapse…"

"A tiger!" teases Elizabeth Ndagire, who lives with depression. "You behave like a tiger… and when you are low, you're like a pussycat… that's what I observe."

Joseph has ended up being a full-time activist for mental health causes. He's a rare voice speaking publicly about his illness, and embracing it. "A normal person who has never suffered from a mental illness but is not happy - I don't want to be that person. I'd rather be me."

But he also admits his activism is a form of therapy. "It's given me a reason to go on, and I'm not sure what I would do without it."

Our World: Uganda, My Mad World is broadcast on BBC World News on Saturday 21st February at 05:30 and 11:30 GMT, and on Sunday 22nd February at 17:30 and 22:30 GMT.

- Published30 October 2014

- Published12 August 2014