France - the Saharan policeman

- Published

“The BBC’s Thomas Fessy joins French patrols stepping into the Sahel region's main militant hotspot”

France has set up a military base in Niger, just south of the Libyan border, hoping to cut off trafficking and supply routes, on which militant groups like Islamic State rely to spread their influence around the region, as Thomas Fessy reports.

Paratroopers from the Foreign Legion are receiving last-minute instructions before they climb in their armoured vehicles.

Engines roaring, they are on the move before the first light. This morning, they will advance through a searing and bitterly cold desert wind.

The temperature sinks to 4C (39F) overnight and at 05:30, the mercury of the thermometer has not started to rise.

These soldiers' mission is not the easiest; they are searching for clues amidst the emptiness.

The Niger-Libya border region is known as the "grey area"

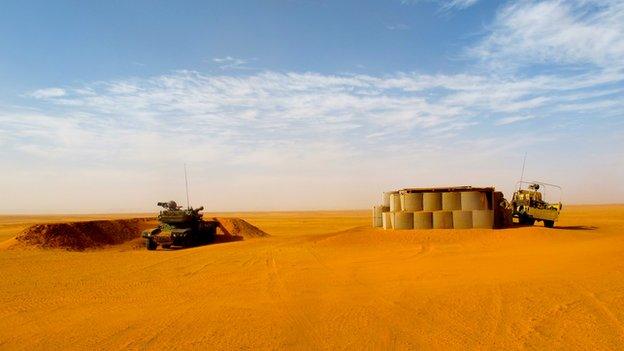

The last French outpost before the border

The French base of Madama, in Niger's far north, is only about 100km (60 miles) from the Libyan border.

"It is a grey area from here to the border," a French senior military source explains.

"The authorities of Niger cannot control it."

In fact, jihadist groups control the west side of the Libyan border while local Libyan ethnic Tubu militia control the east side.

The French are trying to secure this vast zone to stop jihadist fighters and weapons from moving south and destabilising their former colonies in the Sahel region, and potentially linking up with Boko Haram in Nigeria.

"We are worried by the situation in Libya because terrorist groups are regrouping in the Libyan south-west and use it as their rear base," says Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas [French officers on assignments are not allowed to give their surnames], Detachment Commander in Madama.

"These groups cross into Niger and follow the Algerian border to reach Mali, where they supply terrorist groups with weapons," he adds.

"So we are here to keep pressure on them and make sure that they can't go through any more."

Troops and special forces conducting operations on the ground are supported by French jets stationed in Chad's capital, N'Djamena, from where France has operated its 3,000-strong regional Operation Barkhane since August last year.

French Defence Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian announced last week that additional troops would soon join this force. He did not give any indication of the numbers.

Cannabis seized

French war planes and attack helicopters destroyed two convoys that had crossed into Niger from Libya in September and October, Barkhane officials told the BBC.

Both were full of explosives and weapons.

"It's not about the number of men we have," force commander Gen Jean-Pierre Palasset said.

"It's about our ability to deploy very quickly and our capability to be at the right location at the right time."

About 100 fighters have been killed or captured and several tonnes of weapons have been recovered since the beginning of the operation, according to official figures given by Barkhane officials.

The French even seized a couple of tonnes of cannabis in December.

Supplies must be flown into this remote outpost

The armoured personnel carriers stop a first time and align themselves in order to cover a 360' radius. Legionnaires continue on foot, searching the area.

It is an ocean of sand but they follow the coordinates they were given, braving the icy wind.

The second stop will be at the bottom of a rocky mountain. Any trace of recent movements or bivouacs will be reported back.

French-US co-operation

The French and the Americans have eyes in the sky in northern Niger, but these boots on the ground help them map out suspicious activities.

Little by little, the French explore this part of the desert.

France and the US are working in partnership in the Sahel, the arid region south of the Sahara.

The Obama administration provides financial, logistical and intelligence support to the French, leaving them to deploy combat forces.

Operation Barkhane's last outpost before the Libyan border is a tiny shelter mounted on what is called a bastion wall - made of sand bags reinforced with steel mesh.

Looking north in case of Islamist incursions

Guns and binoculars pointed towards the border, soldiers who rotate here are on the lookout.

"Most political actors see this French build-up as a prelude to some kind of military action in southern Libya itself," says Wolfram Lacher, researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

Reliable sources say France has already conducted reconnaissance incursions in Libya's south-west.

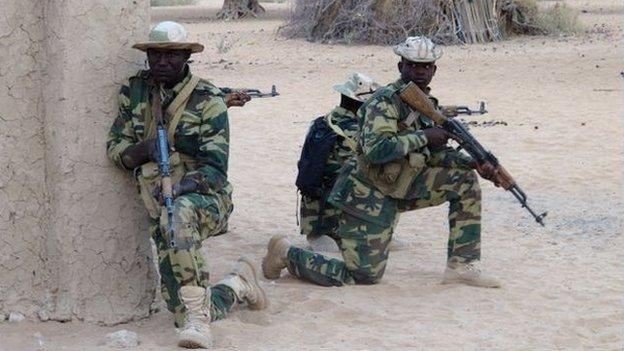

While Barkhane soldiers keep a lonely vigil on the sandy hill, the army of Niger is manning a customs checkpoint a few hundreds yards away.

"We are searching lorries and all vehicles for weapons, drugs and any other illicit goods," says the man in charge, Maj Hassan Ousseini.

This is the gateway to Libya. From here onwards, begins one of the busiest trafficking routes in the Sahara, on which militia and jihadist groups continue to thrive.

'Weapon seizures rare'

It all transits here. For West African migrants who have paid smugglers in Agadez - about 1,000km south - this may be the last peaceful stop before the Libyan "hell", as migrants we spoke to on a previous trip described it.

But on this trip, we are not allowed to talk to any civilians.

"We do catch weapons, especially when we conduct patrols in the area because there are vehicles that bypass our check-point," Maj Ousseini says.

"We go on patrol three or four times a month and that is when we seize vehicles transporting weapons and drugs."

Maj Ousseini admits that seizures remain rare.

Armed groups have learned to dodge patrols and checkpoints over the years.

"It is extremely difficult for the governments of Niger and Chad to prevent cross-border smuggling," Mr Lacher says.

"Influential players have big stakes in this business."

France has become the Saharan policeman

France has deployed about 200 men in Madama.

They are sleeping under tents but Madama is no unknown territory.

This advanced base is taking shape right next to an old fort that the French army built out of dry mud in 1931 to defend themselves against the Italians, first, and then the British.

It is now home to the Nigeriens.

A few hundred kilometres further south, the Nigerien town of Arlit hosts a multi-billion French investment in uranium production, targeted by jihadist groups two years ago.

In Madama, the French are stepping into the region's main militant hotspot, concerned that illegal trafficking will empower groups linked to al-Qaeda or Islamic State across the Sahel.

"These armed groups may channel weapons into Nigeria indeed," Lt-Col Thomas says.

It is believed that a handful of senior commanders from the Nigerian Boko Haram received training in northern Mali when jihadist fighters linked to al-Qaeda occupied it in 2012.

Boko Haram has recently pledged loyalty to the Islamic State. A few days later, an ethnic-Tubu IS member reportedly called on the southern Tubu militia to join IS too.

Mr Lacher downplays any short-term prospects of a "larger alliance between IS and the Tubus", but he warns that even though IS remains marginal in Libya, it is growing rapidly.

"Our operations are aimed at stopping the flow of logistical support that terrorist groups based in Libya can provide in Nigeria and Mali," insists Lt-Col Thomas.

The former colonial power, France, today stands as the Saharan policeman and has made it its mission to break the shifting allegiances between extremist groups.

But with Boko Haram to the south and an expanding Islamic State to the north, the regional outlook is not too promising.

- Published23 January 2020

- Published9 March 2015

- Published3 March 2015

- Published19 February 2018