After Garissa attack, grief and questions in Kenya

- Published

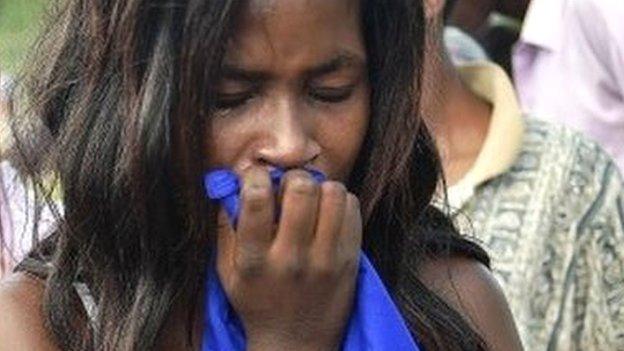

I watched mothers, fathers, other relatives and friends break down in tears at Chiromo mortuary in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, as coffins of their young sons and daughters were handed over.

There could not have been a more poignant moment to witness the deep pain and grief suffered by families of those who perished in the Garissa University College attack last week.

They are taking their children home to the hills and valleys of this beautiful land for burial.

Everyone has been touched by the gruesome attack.

While I was at the mortuary, I saw Kenya's Foreign Affairs Minister Amina Mohamed break down in tears at the scale of personal loss all around us.

Foreign Minister Amina Mohamed was distraught when she visited the mortuary

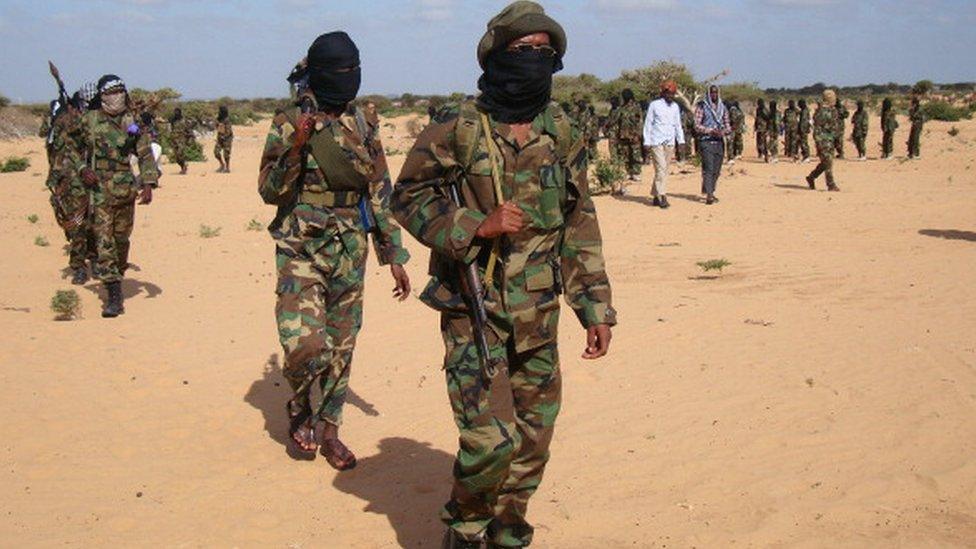

The question that comes to mind is - why? Why were those young people targets for the Somali-based al-Shabab militants?

And why Kenya? The simplistic answer is that Kenyan troops are serving in the African Union mission in neighbouring Somalia and the insurgents are striking back.

Home-grown terrorism

So if the troops pull out of Somalia, as the opposition is demanding, will that stop the attacks?

"It is time that we look into... how our troops can withdraw from Somalia," former Prime Minister and leader of the opposition Raila Odinga told an Easter gathering in Mombasa.

Residents of Nairobi's Somali district protested against al-Shabab but have been hardest hit by the closure of money transfer firms

"The US used to have many soldiers in Somalia but it recalled them.

"Kenya should also remove its military officers from Somalia."

Yet as we have seen in other parts of the world, terrorism can be home-grown too.

It was not just Somalis who were involved in the Garissa attack - at least one of the four gunmen has been identified as a Kenyan national.

And this week's closure of 13 money transfer firms, a lifeline to the Somali community and many other Kenyans, has angered many.

The government says it is to prevent militant Islamists from using them to finance attacks, but aid agencies say the closure will hit poor Somalis hardest as they rely on remittances for food, school and basic health care.

President Uhuru Kenyatta has also been singled out for criticism because it is more than a week since the attack and he has not visited Garissa yet.

President Kenyatta is yet to meet victims of the Garissa attack

Questions too are being asked about why the authorities ignored intelligence reports ahead of the attack.

And fingers pointed at security lapses and the apparent response to the attack.

Manoah Esipisu, who speaks on behalf of the president, openly admitted that "mistakes were made".

An elite paramilitary unit arrived in Garissa at 13:56 local time. The alarm had been raised at 06:00.

Ngunyi Yusuf, former banker:

"The government must shut down the Dadaab refugee camp and send those people back to Somalia"

Back at the mortuary I heard about 23-year-old Susan Kwamboka Onyikwa.

She was studying to become a teacher and her uncle Ngunyi Yusuf, a former banker, had come to fetch her body.

"Susan was marvellous. She loved cooking and being at home. She was loved by everybody in the family," he told me.

With tears swelling in his eyes, the 42-year-old continued calmly: "She was a very good lady. We are devastated."

When I asked Mr Yusuf what the government should do to avoid another attack, he pointed to the nearly 500,000 Somali refugees who are in the country, having fled decades of conflict and hunger.

"The government must shut down the Dadaab refugee camp and send those people back to Somalia."

As the hearse carrying Susan Onyikwa's body slowly left Chiromo morgue for Nyanza in the west, it was clear that Kenyans want peace. But they know all too well that in these troubled times, there are no guarantees.

- Published5 April 2015

- Published7 April 2015

- Published3 April 2015

- Published22 December 2017