Kenya's ivory inferno: Does burning elephant tusks destroy them?

- Published

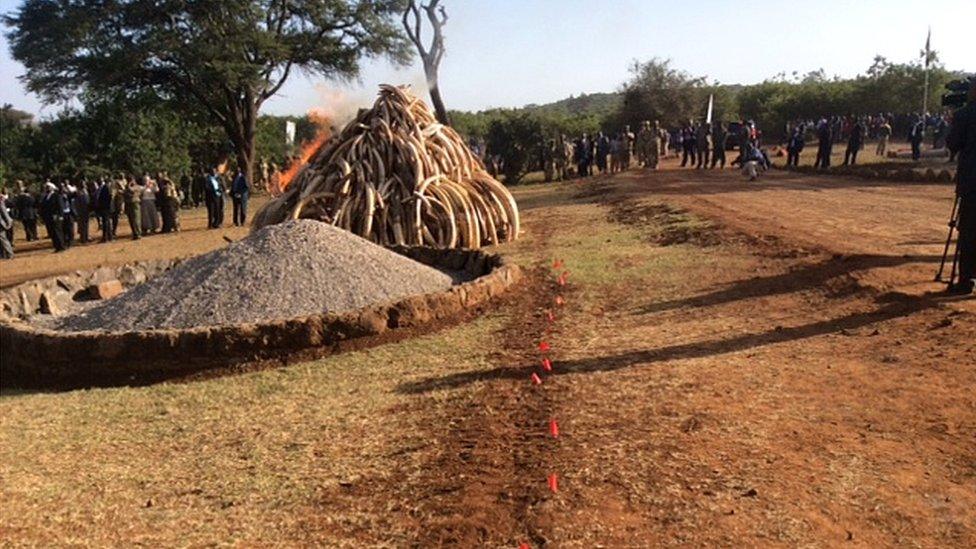

The tusks of some 6,700 elephants have been piled in pyramids ready to be set alight on Saturday

The largest ever pile of ivory will be set alight in Kenya on Saturday. But will it actually burn?

The fire will be seven times bigger than any previous ivory fires - 105 tonnes of tusks have been piled in pyramids, some three metres high (10 feet).

The idea is that this will help tackle the illegal ivory trade and curb poaching, which is killing some 30,000 elephants a year.

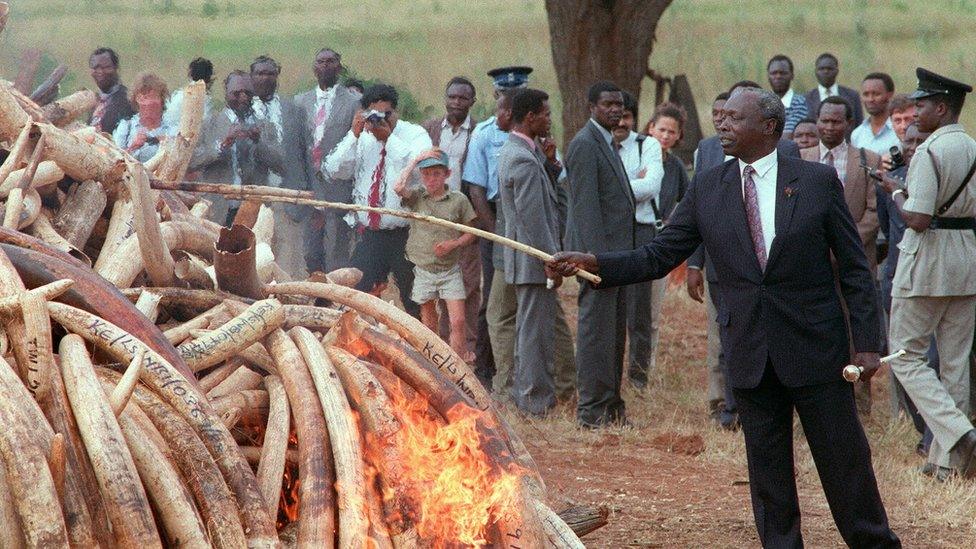

The practice of burning ivory goes back to July 1989 when Kenya's then-President Daniel arap Moi ignited a pile of 12 tonnes of elephant tusks and helped change global policy on ivory exports.

After that, the trade was banned under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

This was a "desperate measure meant to send a message to the world about the destruction through poaching of Kenya's elephants," says Paul Udoto from the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS).

Since then many countries have followed suit but does setting fire to ivory actually destroy it?

The first time ivory was burnt in public was in 1989 by Kenya's then-President Daniel arap Moi

The US chose to crush, rather than burn, one tonne of its ivory stockpile in public last year, external because ivory "doesn't catch fire the way you might imagine but rather just chars on the outside", says Gavin Shire from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

Other countries have also opted for the crushing method.

One week to burn a tusk

The FWS forensic laboratory carried out an experiment in 2008, external where it set fire to a piece of ivory at an ultra-high temperature.

The results, quoted by National Geographic online, showed that burning ivory at 1,000C led to it losing just 7g per minute - meaning that it would take around a week to destroy an average male elephant tusk.

If the ivory is left to burn for long enough at a high temperature it does get reduced to ashes

Kenya has become something of an expert in the field of burning ivory, having done it three times, and is well aware of the time and effort needed to destroy the tusks.

According to the KWS, after the dignitaries have driven off the pyre continues burning for at least a week.

Jet oil

Kuki Gallmann was one of those behind the 1989 fire and knew, from an experiment with some ivory in a domestic fire, that a high temperature was needed.

She helped devise a method using jet oil and a network of pipes under the tusks, which has been used on the other two occasions that Kenya has set fire to ivory, said Mr Udoto.

The ash pile from Kenya's 1989 fire can still be seen in the spot where it was burned

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) says that 14 countries have carried out ivory destructions, external through either burning or crushing - or sometimes a mixture of both.

But there is a wider debate about how effective these acts are when it comes to ending the illicit ivory trade and reducing poaching.

"The destruction of ivory is a political mechanism to signal the government's commitment to curbing elephant poaching," says Tom Milliken from Traffic, which monitors the trade in wildlife.

"But there is no proof that destroying supply leads to a decline in demand."

The WWF argues that destruction should be combined with greater efforts on the ground to combat poaching.

Even though it may be difficult to actually destroy 16,000 tusks through burning, as the KWS's Mr Udoto says, it has been a way "to get the world to listen to its message" about the dangers of wildlife poaching.

- Published2 June 2014

- Published21 July 2014