Why are South African students protesting?

- Published

South African universities have been affected by the biggest student protests to hit the country since apartheid ended in 1994.

South Africa's president has warned that the protests, which have caused about $44m (£34m) in damage to property in the last few weeks, could threaten to sabotage the country's entire higher education system.

What sparked the protests?

In 2015, proposed tuition fee hikes of between 10% and 12% sparked protests.

The demonstrations began last October at Johannesburg's University of the Witwatersrand when students blocked the entrance to the university campus, following indications that the institution would raise fees by 10.5% for 2016.

The demonstrations, under the banner #FeesMustFall, led to the closure of some of the country's top universities - and President Zuma ordered a freeze on tuition fees for a year.

The BBC's Milton Nkosi reports from Wits University where police have been using stun grenades and rubber bullets

But protests erupted again last month after a government proposal to raise tuition fees by up to 8% in 2017.

They are now demanding free education for all students.

Which students are affected?

The government says it will subsidise the increase for students from families earning up to 600,000 rand ($45,000; £36,000).

However this seems to have gone largely unnoticed.

Many of those protesting are arguing that they come from poor families, and despite the government promise, fear the increase will rob them of the opportunity to continue studying.

Students say the fee hikes amount to discrimination in a country where the average income of black families is far less than that of white families.

They want free education for everyone, starting with the poor and "missing middle"- those whose parents have jobs but don't make enough to afford tertiary education.

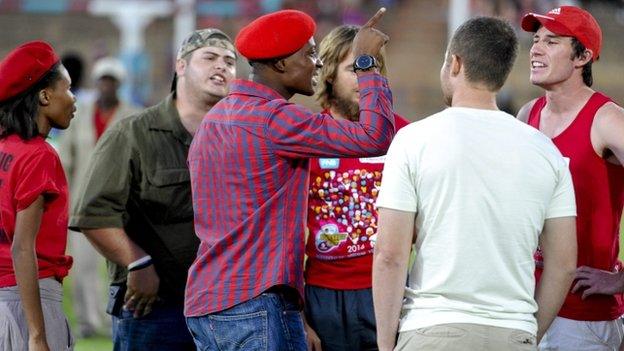

Lecturers and students protest in support of the free education movement

Extreme income inequality remains a persistently stubborn problem more than two decades after the end of apartheid in 1994.

Correspondents say the protests show growing disillusionment with the governing African National Congress (ANC), which took power after 1994, over high levels of poverty, unemployment and corruption in government.

The students want the opportunities promised when apartheid ended.

How are university fees determined?

Annual increases in student fees differ between universities as fees are determined by institutions. Fees also vary across degree programmes.

Students protesting under the #FeesMustFall banner

Universities have three main sources of income: Government subsidies, student fees and private sources. The number and financial background of students influence individual university subsidies, external.

While government funding for higher education has increased by nearly 70% since 2001, according to news organisation Ground Up, external, student enrolment numbers have also increased leading to a decrease in the subsidy per student.

In addition South African institutions want to provide a "world class" education and argue that they battle to maintain standards amid financial constraints.

Why did the protests spread?

The proposed fee increases are not exceptional in comparison to usual annual increases, which are often between around 7% and 14%. While there have been protests about fees at individual universities in previous years, the national scale of these protests over the last 12 months has been unprecedented.

It seems impossible to separate the protests from demonstrations earlier in 2015 around a lack of transformation at South African universities more than two decades after the end of white-minority rule.

Apartheid and education:

One of the main laws of apartheid was the Bantu Education Act of 1953

It prevented black children from reaching their full potential

A black education department compiled a curriculum that suited the "nature and requirements of the black people". The aim was to prevent Africans receiving an education that would lead them to aspire to positions they would not be allowed to hold in society

A move to "decolonise" higher education was sparked when politics student Chumani Maxwele emptied a bucket of excrement over the statue of British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town's (UCT) campus in March 2015.

The statue of British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes was removed from the UCT campus in April 2015

The statue was eventually removed, but similar movements formed at other universities calling for diverse academics and changes to curriculum. This gave the movement a springboard: To correct the historical legacies of apartheid in higher education.

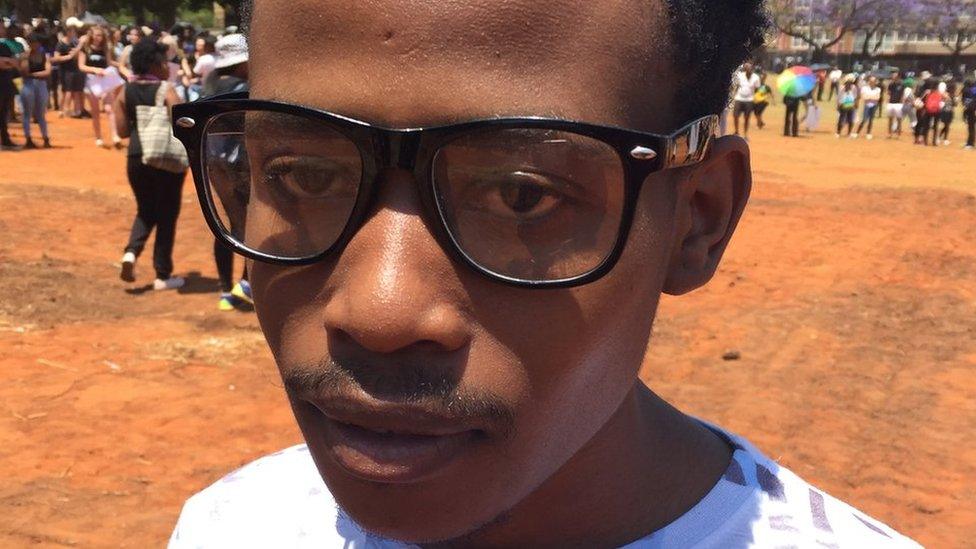

Students are fed up waiting for the opportunities promised in 1994

Can students' demands be met?

In the wake of last year's protests, President Zuma set up a fees commission, chaired by a judge, to look at whether South Africa can afford free education.

The findings were supposed to be released in August, but this has been delayed until April 2017, adding tension to the latest demonstrations.

Roshuma Phungo of the South African Institute of Race Relations has said free education is possible.

"If higher education was to be funded solely through taxpayer subsidies then a further 71bn rand ($5.2bn £3.4bn), over and above the existing R25bn [current government subsidy], would be necessary," she wrote in the privately-owned Daily Maverick, external in 2015.

"Our analysis suggests that, with sufficient prioritising, that 71bn rand could be raised."

Adam Habib, vice-Chancellor of Wits University which tried to reopen for classes this week, says the prestigious institution cannot provide free education.

"We have said multiple times to the student leadership we cannot deliver free education... Wits University is prepared to commit to free education to the poor and the missing middle," he told 702 Talk radio.

- Published23 October 2015

- Published30 March 2016

- Published2 September 2015

- Published11 April 2015

- Published2 February 2011

- Published25 March 2015