Gay Ugandans regret fleeing to Kenya

- Published

Hundreds of LGBT Ugandans who have fled to Kenya for safety, are facing harassment and attacks, reports Emmanuel Igunza

Hundreds of people in Uganda's lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community have fled the country to escape homophobia and persecution. But many are now stuck in Kenya where the situation is not much better.

Tyrone, not his real name, has had a tough time since arriving in Kenya in December 2014.

Just days after arriving in the country he was beaten up by a mob in the capital, Nairobi.

It was Christmas Day.

Since then the 19-year-old has been arrested and beaten up by police three times.

He told me on one occasion three policemen called him over and asked him why he was "walking like a girl".

"When I couldn't answer them, they beat me up and when they saw on one of my documents that I was a Ugandan refugee, they abused me saying I was one of the people Museveni [Uganda's president] had kicked out of the country for being gay."

He has moved house several times after being attacked by neighbours.

Tyrone is one of more than 500 Ugandans who have escaped to Kenya, to apply for asylum and be resettled abroad on the basis of their sexual orientation.

His country made international headlines in recent years when it tried to introduce a tough new anti-homosexuality law, which allowed life imprisonment for "aggravated homosexuality".

Although the courts struck it down, the environment has proved too dangerous for a growing number of Ugandans.

But in Kenya they face constant attacks, kidnappings, extortion and police harassment.

Recently, almost a dozen LGBT people were taken by the United Nation's refugee agency (UNHCR) to a safe house in Nairobi, after they were attacked on a night out.

The Ugandans stand out in this refugee camp as they are the only residents fleeing a peaceful country

Even that agency - the very group tasked with protected LGBT people - has admitted its own staff are hostile.

The deputy head of protection for UNHCR told me that staff have said that as Christians they could not work with, or talk to, a gay man.

"It's difficult for people to go beyond all the prejudices they have. And this is what we faced with our own colleagues," Catherine Hamon explained.

Some of the Ugandans I spoke to also told me this discrimination from UNHCR staff has led to delays in determining their refugee status, making them live with uncertainty about their future.

The situation is no different for those who choose to live in refugee camps.

Standing out

Kakuma camp in the remote north-west is home to nearly 200,000 people - mainly from conflict-ridden places such as South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and the Great Lakes region.

So the Ugandans - whose country is considered peaceful - stand out.

They live in three compounds, tucked away in a corner of the camp.

One of the group leaders, a tall, deep voiced middle-aged man, says living together offers them protection in numbers.

But it has also made them easy targets for other refugees.

"In Uganda we were unsafe and here it's the same," said Blessed, not his real name.

He was a church pastor in Uganda and fled to Kakuma 18 months ago after his name was published in a local newspaper, which said he was gay.

He received death threats and had to leave his family behind.

"I don't know if I will ever see them again," he said.

"First I have to survive being here and then maybe one day I can entertain that thought."

The Ugandans have to sleep in shifts - taking it in turns to guard their compounds at night, after an attempt this year to burn it down.

And that is not the only threat they have received.

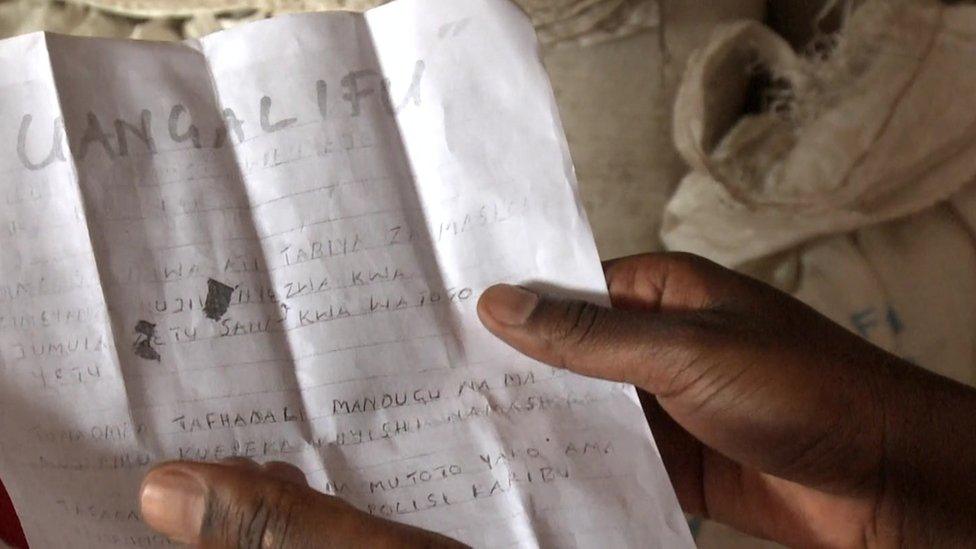

A few weeks back, hate leaflets were circulated around the camp asking people not to mix with the LGBT community there.

This leaflet, in Swahili, asked the camp's residents not to mix with gay people

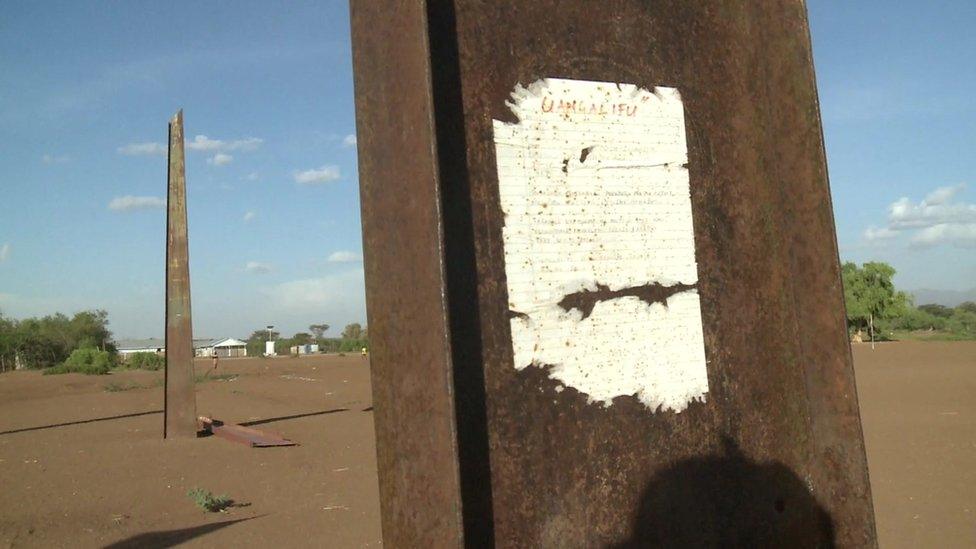

Despite reporting the incident to the police station - situated about 300m (328 yards) from their compound - we still managed to find one such leaflet stuck to a pole near one of the camps.

Not all the anti-gay posters had been taken down

"It is such incidents that just show we are not wanted here," said Helen, who teaches at one of the dozens of schools in the camp.

Like many of the Ugandan refugees in Kakuma, Helen is well educated and had a well-paying job as an events manager in Ugandan.

Now she barely gets by.

"What kills me most is the uncertainty of this place.

"I don't have any hope here - any hope of going back home or seeing my partner, and any hope of getting my refugee status resolved."

Waiting game

The UNHCR says it faces a backlog of more than 20,000 cases of all refugees in the country, just waiting for their status to be determined.

"Back in February, traffickers took advantage of what was happening in Uganda and we started seeing huge numbers of people coming in, claiming to be gay or lesbians," explained Ms Hamon.

While they are still offering people from the LGBT community a fast track in registration, she admits it is not as fast as before.

The initial group of refugees who came to Kenya from Uganda were resettled abroad within six months - a record time of because of the unique security challenges they faced.

The US, Canada, the UK and Scandinavian countries were the most receptive to the Ugandans.

Now it will take around two years to go through the whole process, according to Ms Hamon.

So people just have to wait.

And for people who are still in Uganda, Tyrone has a stark message.

"If there is a way they can keep themselves underground there [in Uganda] they can make it because Kenya is a far worse place for gays than Uganda."

- Published10 February 2014

- Published24 January 2014

- Published7 December 2011

- Published26 April 2023