Nameless dead of the Mediterranean wash up on Libyan shore

- Published

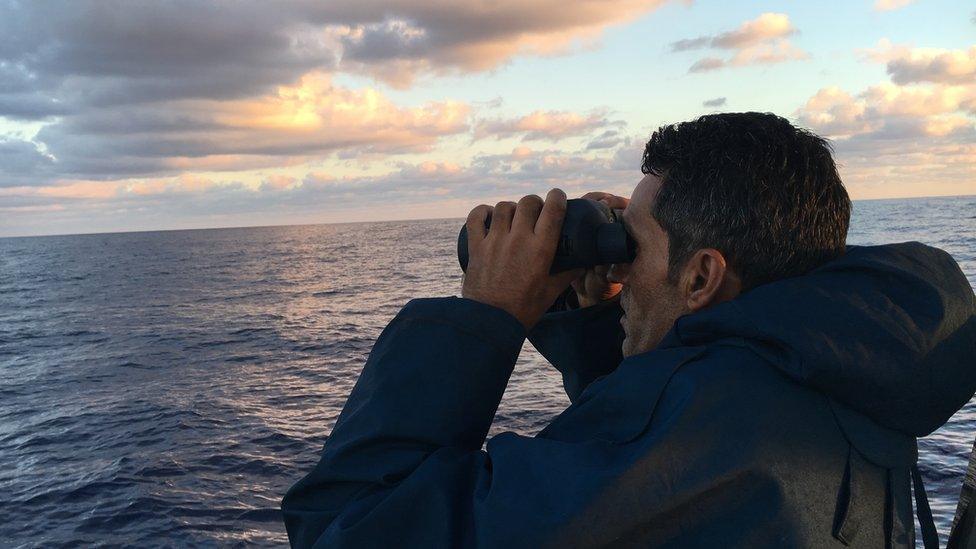

Migrants often cross the Mediterranean in rickety boats to reach Europe

Only the leg was visible on the beach, protruding from the Libyan shoreline, as though in silent rebuke. The battered body it belonged to was entombed by the sand.

"God covers them when they come out of water," said Abu Bakr Al Soussi sombrely.

The young Libyan photographer documented this unidentified corpse, and almost 20 others, on the shores at Garabulli, east of the capital, Tripoli, in March.

As a volunteer with the Red Crescent, he may have to photograph many more. They are part of a strange and terrible harvest from the seas - the nameless dead of the Mediterranean.

So far this year, more than 3,000 migrants and refugees have been claimed by the waves as they tried to reach Europe, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

'Sleeping on a body'

But Betty, a 29-year-old single mother from Nigeria who did not want her surname to be published, is undaunted at the prospect of crossing the sea in an overcrowded inflatable boat. Small wonder perhaps. She has already been deceived, trafficked across the Sahara desert, beaten, and brutalised.

Betty tells of her struggle to get to Germany

A smuggler back home had promised her a job in Egypt. But after she paid him 200,000 Nigerian naira ($645; £490), she was loaded onto a truck for a harrowing journey to Tripoli.

"A lot of people die in the desert. When anybody fell down, they were not going to wait. I saw so many dead bodies. I was crying," she told the BBC.

"If you shout you would be killed, instantly. Even when we lay down in the desert, we did not know we were sleeping on top of a dead body. It was when we removed our blankets that we saw - ah this is a skeleton. "

On arrival in Libya, there was "another pain entirely", Betty said.

She was delivered to a gang which tried to force her into prostitution. She had to buy her freedom by borrowing more money. Now she has paid another trafficker 1,200 Libyan dinars ($860;£655) to take her to Europe.

She says she has no choice.

"I need to go because I am a single mother of two boys. I need to go to Germany," Betty told the BBC.

"Things are not easy there too I know, but it's much better than Nigeria. My children need to go to school. They need to have a better life."

Mohammed Garbaj of the Tripoli Coastguard has come across many like Betty, dead and alive. The wiry and weather-beaten skipper has rescued countless numbers, but is haunted by those he could not save.

"One time we went to rescue a boat but unfortunately we found only one person alive," he said.

"All the others had drowned - there were 120 of them. The people who send them on these boats are not good Muslims. They are heartless, sending people to die in the sea."

'Taxi service'

We joined Mr Garbaj on a search for smugglers and migrants in distress, leaving port in a 12-metre inflatable. It is the only seaworthy vessel the Tripoli coastguard has - they cannot afford to repair the other three.

Some of Libya's beaches are strewn with the belongings of those who drowned

People leave Africa because of poverty, war or political persecution

Mohammed Garbaj tries to save migrants whose boats capsize

In pitch darkness Mr Garbaj and his crew switched off their engine and listened out for migrants' vessels. There was little else they could do. They did not have night-vision goggles, and their radar did not detect small boats. They admitted it was the traffickers who ruled the waves.

"The smugglers have more boats and more weapons," said Mohammed Boushagour, a young crewmate.

"They have long-range guns. They can escort the migrants to European waters and we can't do anything to stop them. The state doesn't support us. We haven't been paid since March," he added.

Coastguard officials say there is another problem - Operation Sophia.

The European Union mission, which operates just beyond Libya's territorial waters, was supposed to disrupt smuggling.

Instead, it is providing "a taxi service for migrants", Colonel Ashraf Al Badri, head of the Tripoli Anti-Smuggling Unit, told the BBC.

"From my point of view, it's indirectly encouraging the migrants to go to Europe. Now, they have to travel just 12 miles. Then Operation Sophia rescues them. They are given food and taken to Europe," he said.

"Of course, this information spreads. The migrants all know that instead of a dangerous journey lasting more than a day, they will get picked up in four or five hours."

Many migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa pass through Niger on their way to Libya

That view was echoed by a smuggler, now in detention in Tripoli, who the authorities described as a big fish.

"The operation saves life," he told the BBC, "and encourages people to travel more."

But the IOM argues that with or without Operation Sophia, migrants and refugees will try to reach Europe.

"I can understand what the Libyans are saying about a pull factor, but people will always find ways," said its spokesman Itayi Viriri.

"We shudder to imagine what the situation would be like without a concerned rescue effort. The issue of saving lives is paramount."

'Not afraid'

Those saved by the Libyan coastguard wind up in detention centres like Abu Salim, on the outskirts of Tripoli. Hundreds are trapped here in what amounts to an airless mini-prison, women and children among them. The youngest detainee we saw was a 21-day-old baby called Mahmud.

These migrants agreed to be sent back home to The Gambia

Many of those we met there were economic migrants, like a 14-year old from The Gambia, in a red and white striped hat.

He said he had travelled to Libya alone in the hope of crossing to Europe and finding a job.

"I come from a poor family. I wanted to get to Italy, so I can feed my family. They have not heard from me for two months. They will think I am dead," he added.

His countryman Abdul Jayie, who is 18, told us the detainees were kept inside for a month at a time. "Sometimes there are 200-300 people. We all share two toilets. I feel shame at being a prisoner. I want to go home."

The authorities say they are doing their best, with scarce resources, at a time when Libya is barely afloat.

"The [food] supplier to our camp gets his money from the state, and he hasn't been paid for a year," said Ramadan Rais, the head of Abu Salim.

Many of the detainees are visibly desperate to be released. That only happens if they agree to be deported, like the 160 Gambian men who left the centre recently.

"Going back home will be like going to paradise," one man said as he queued for a bus. "I want to see my mother."

Back on the seashore, Betty is barefoot, with the waves lapping at her feet.

"I am not afraid," she said. "My mind is strong because I believe in God. Every time I look at the sea I say to the water: 'You are not my limit. Nothing will happen to me'."