Migrant crisis: EU to boost Africa aid to stem influx

- Published

Migrants in Tripoli: Many Africans are fleeing chaos and violence in Libya

The EU has presented a new aid plan to curb the influx of African migrants via Libya, building on the deal it reached with Turkey in March.

The European Commission aims to boost partnerships, external with nine countries in the Middle East and Africa, including Jordan, Libya, Ethiopia and Nigeria.

EU Migration Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos said project funding could eventually reach €62bn (£48bn; $70bn).

Controversially it may include security help for Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan.

More than a million refugees and economic migrants entered the EU via the Mediterranean last year, many of them fleeing chaos and civil war in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

Hundreds also drowned in tragedies at sea, when overcrowded, flimsy boats sank.

Measures for Africa

The numbers reaching Greek islands from Turkey have dropped sharply since the EU-Turkey deal, external took effect in March. Migrants with no grounds for EU asylum are being returned to Turkey, which has been promised extra EU aid and visa-free travel in exchange.

Despite that drop, the numbers reaching Italy on the central Mediterranean route have remained similar to last year's pattern, with more boats leaving Libya in the good weather.

On that route the main countries of origin are: Nigeria (15%), Gambia (10%), Somalia (9%), Ivory Coast, Eritrea and Guinea (8% each) and Senegal (7%), the UN refugee agency UNHCR reports, external.

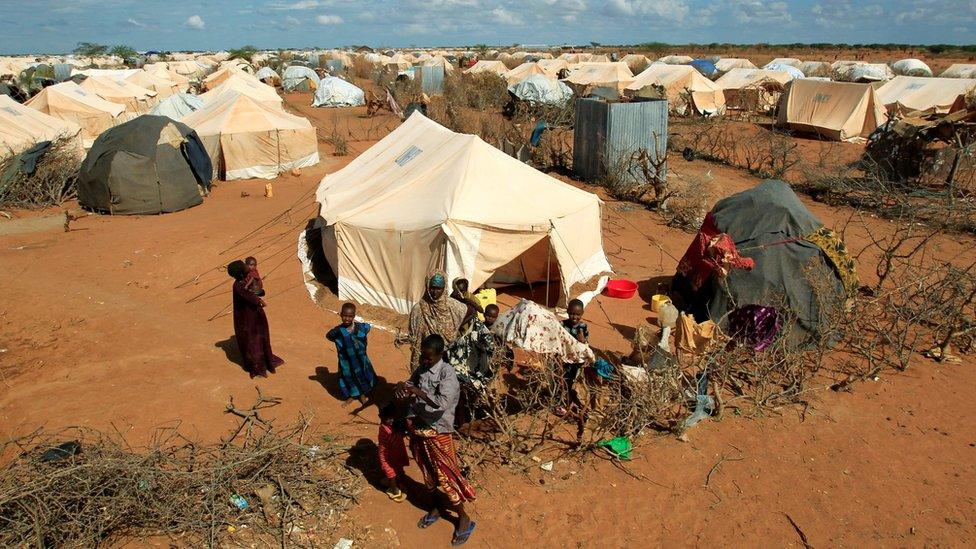

Kenya plans to close the Dadaab camp - but many Somali refugees could be at risk again

At a Malta summit in November, the European Commission, which drafts EU laws, agreed to put €1.8bn into an Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

The aim is to combat people-trafficking gangs and reduce the incentives for sub-Saharan Africans to make the hazardous journey to Europe. That includes creating jobs and tackling extreme poverty in their home countries.

Currently no more than 40% of failed asylum seekers are accepted back by their home countries, so the EU also wants to boost those numbers. Countries that fail to co-operate could face cuts in the EU aid they receive.

Mr Avramopoulos said €8bn of EU budget funds could go into the migration partnership in 2016-2020. But in the long term the commission believes it can attract bigger sums in private investment.

The migration pressure from Africa is expected to keep growing in coming years.

EU partnership programmes specially tailored to each country's conditions are being developed for nine countries initially: Ethiopia, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Tunisia. The plan is to expand such aid later to more countries.

Human rights concerns

The EU package will include provision of border surveillance equipment, police training and other technical support to stop migrants heading north.

That is especially controversial in the Horn of Africa, where the commission has already mapped out €40m worth of projects , externalas part of the Emergency Trust Fund.

Eritrea and Sudan are subject to international sanctions because of alleged large-scale human rights abuses, which both governments deny.

There is concern that Kenya's decision to close the world's biggest refugee camp - Dadaab - could boost the numbers heading to Europe from the Horn. Dadaab houses about 350,000 people, mostly from war-torn Somalia.

On Monday EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini said "we too often forget that countries like Ethiopia or Kenya, let alone Lebanon and Jordan, host huge numbers of refugees. The closure of the Dadaab camp in Kenya could have dramatic humanitarian consequences".

Mr Avramopoulos said the commission would also relaunch the Blue Card scheme , external- a way for the EU to attract skilled professionals from non-EU countries.

Launched in 2012, the scheme has made little progress - in 2014 only 13,852 Blue Card work permits were issued, about 12,000 of them provided by Germany.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.