Is this the end for the International Criminal Court?

- Published

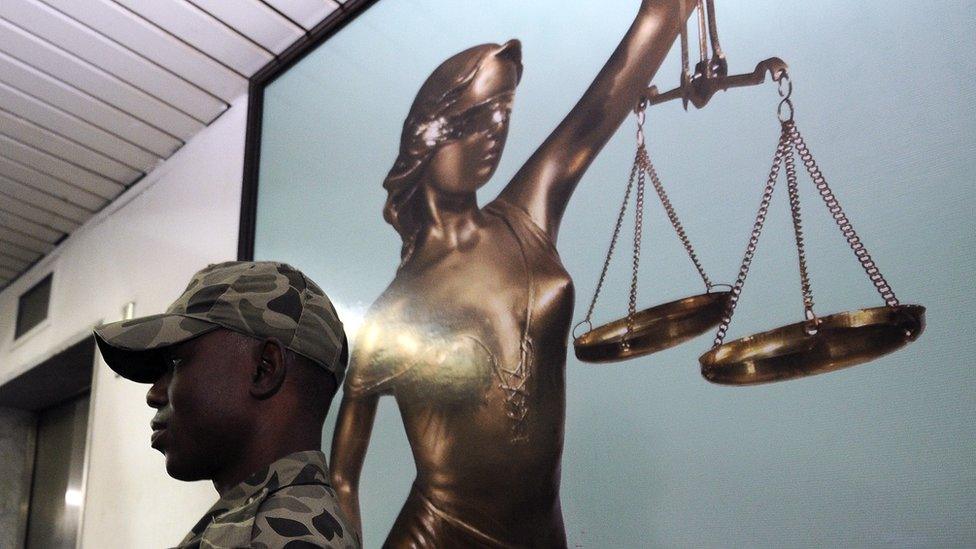

The threatened departure of one of the founding fathers of the world's first permanent war crimes court feels like Africa's Brexit moment.

South Africa has formally begun the process of withdrawing from the International Criminal Court (ICC), notifying the UN of its decision.

The government concluded that membership of the ICC created a conflict with its role as a regional peace broker.

It looks like the news came as a surprise to the UN secretary general.

"We didn't see this coming" said a source close to Ban Ki-moon. "The UN Secretary General was totally shocked".

But perhaps the UN should have seen this coming.

'Hypocrisy'

Significant numbers of people across Africa appear to be tired of what they see as the court's bias, with the vast majority of cases coming from this part of the world.

Earlier this year the African Union threw its weight behind a proposal to leave the ICC.

Then Burundi - itself the subject of a so-called preliminary examination by the ICC for alleged post-election violence in 2015 - fired its opening salvo.

It became the first state to announce it was leaving the court.

Why South Africa is leaving the ICC

Luis Moreno Ocampo, the former ICC chief prosecutor, pinpoints the moment when attitudes changed:

"I remember South Africa as a champion, it was leading the continent under Mandela and Mbeki... under President Zuma, it's different," he told the BBC.

"Who will stand for the African victims when leaders conduct massive atrocities to stay in power? Who will prevent Burundi from slipping into genocide? We're slipping backwards".

He accused many leaders on this continent of "hypocrisy" - claiming that publicly they vilify the ICC to appease their African Union allies, while privately supporting its ideals.

'I'm the judge'

Yet some of the most respected African legal minds are themselves uncomfortable with its inherent contradictions.

Not least the fact that the US refuses to become a member or be bound by its rules.

"Some of the world leaders are part of the judging but they're not bound by it.

"It's like saying: 'I'll be the judge but me and my children will not be bound by it.' It creates a very unhealthy dynamic," argues Thuli Madonsela, South Africa's former anti-corruption chief.

Yet despite its shortcomings, like many others Ms Madonsela is sceptical about wholesale withdrawal.

"Better to have an imperfect court than none at all. It's like saying because we don't catch all the criminals we shouldn't hold trials."

Nevertheless there is widespread expectation that other countries may soon leave.

Kenya could be poised to throw in the towel, after a sustained campaign to paint the court as a "neo-colonialist" institution and the subsequent collapse of cases against President Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto.

How Kenyatta led Africa's opposition to the ICC: By Dickens Olewe, BBC News

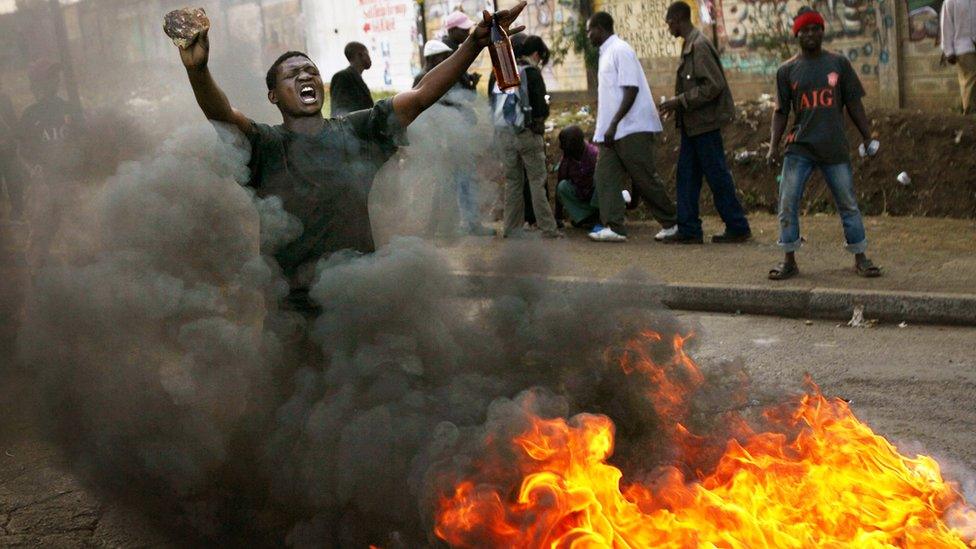

The African onslaught against the ICC was started by Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 when he said the court was "race hunting" on behalf of its benefactors and being used as a tool to oppress Africans.

He was speaking at a special African Union summit called to discuss a mass withdrawal from the ICC.

Both Mr Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto were charged by the ICC in connection with post-election violence in 2007-08 - charges that were later dropped.

Mr Kenyatta called the court a "farcical pantomime" which was no longer a home of justice.

He criticised the US and EU for arm-twisting African countries to submit to the court's will.

"Africa is not a third-rate territory of second-class peoples. We are not a project, or experiment of outsiders," he said.

He called for unity and a focus on "African solutions to African problems".

Chad, DR Congo, Central African Republic and Ivory Coast could follow suit, emboldened by South Africa's threatened departure.

But beyond the indignation of the human rights community, are global leaders queuing up to loudly condemn the move?

No. In a post 9/11 world it would seem that the fight against terrorism trumps justice.

Is it time for regional leaders to sort out affairs in their own back yard or assert their position in institutions like the ICC?

The ICC eventually dropped charges against Kenya's president over post-election violence

Mr Ocampo argues that African leaders should use the "tools" of the court to develop a level playing field with the world's superpowers by holding countries like the US to account.

One way they should do this, he argues, is by supporting the ICC's preliminary examination into the alleged mistreatment of detainees by US and coalition forces in Afghanistan.

It may be an academic point but it requires unanimity of purpose among the very leaders who are the biggest critics of the court.

Despite the well rehearsed rebuttal that many of the cases heard by the ICC are referred by African states, the issue of bias has been a sustained part of the anti-ICC narrative.

"Preliminary examinations" now include alleged war crimes committed in Colombia, Afghanistan and by the UK in Iraq. But could it be too little too late?

Sabotaged cases

The protection of witnesses at the court has also exposed severe weaknesses.

Last week former Congolese rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba was found guilty of witness tampering.

Interfering with witnesses has sabotaged ICC cases.

The intimidation of prosecution witnesses in the cases of Kenya's president and his deputy, led to their trial's eventual collapse.

The court has no police force of its own to arrest indicted war criminals and only limited financial means of protecting witnesses who testify.

So many who may have had crucial evidence which may have helped convict powerful leaders have retracted their statements and sought sanctuary in silence.

The ICC and global justice

Came into force in 2002

Gambian lawyer Fatou Bensouda (pictured) is the ICC's chief prosecutor

The Rome Statute that set it up has been ratified by 123 countries, but the US is a notable absence

It aims to prosecute and bring to justice those responsible for the worst crimes - genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes

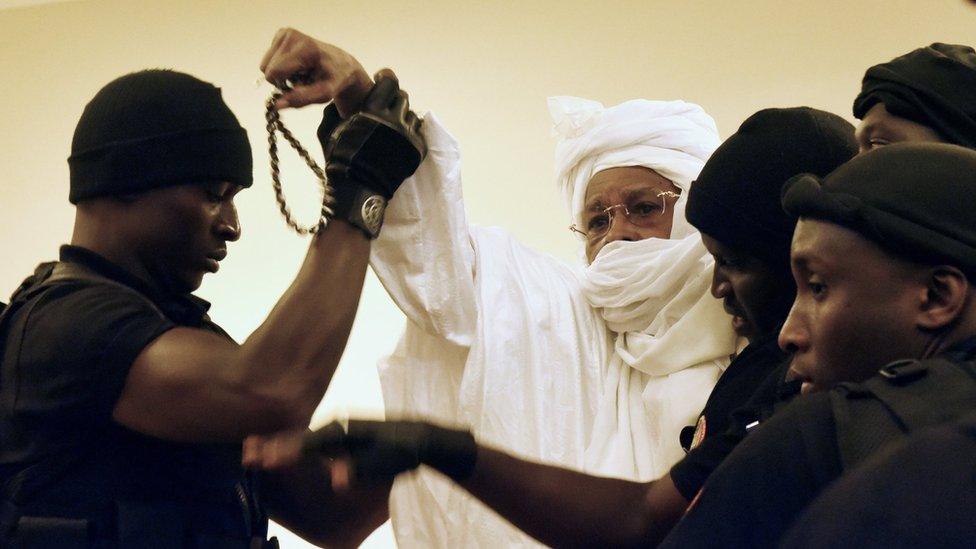

An alternative to the ICC, argue many African Union members, is to bolster Africa's own institutions.

The conviction of Chad's former leader Hissene Habre by a court in Senegal earlier this year is a clear indication that there is a hunger for justice.

But is there the political will to strengthen regional courts?

"I like the idea of regional courts but the problem is that there's always regional politics to it," says Ms Madonsela.

Many would agree there is no shortage of expertise and technical talent on the continent but promises to strengthen regional courts have moved at a glacial pace.

Chad's former leader Hissene Habre was sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity, in the first African Union-backed trial of a former ruler

The African Court on Human and People's Rights was established under the auspices of the African Union in 2009 but it has found itself mired in bureaucracy, delivering just one major judgement in 2009.

Shadrack Gutto from South Africa's Institute for African Renaissance Studies agrees it is time for reform but says the African Union should consider a system which works in parallel to the ICC - not scrap it altogether.

"We have a lot of corporate crimes being committed in Africa and yet they are not being dealt with by the International Criminal Court.

"We could set up a mechanism to deal with this. There are weaknesses at the ICC for sure but that does not mean we should allow ourselves to just simply move out."

It is likely to take the conviction by the ICC of a leader who hails from outside the African continent, before that view gains currency among sceptics.

But is the court running out of time?

Or will it take another genocide, as Mr Ocampo suggests, to anchor justice firmly to the process of long-term global peace?

- Published7 February

- Published14 October 2015

- Published5 April 2016