Senegal truckers tired of taking the long way around The Gambia

- Published

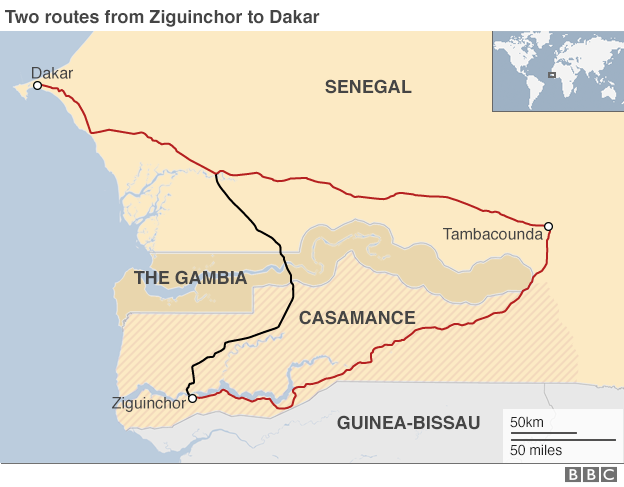

Travellers between north and south Senegal are currently being forced to take a 10-hour detour because of a trade dispute between Senegal and The Gambia, an Anglophone enclave which sticks into the heart of its much larger, French-speaking neighbour.

Of all the artificial borders drawn up in Africa by the colonial powers in the 19th Century, one of the most ridiculous has to be that between the two countries.

The Gambia, colonised by the British, is a thin sliver of land either side of the eponymous river, surrounded on three sides by Senegal.

On either side, people share the same culture and local languages but those who have been to school are divided by the language in which they were instructed.

And the tiny Gambia is always keen to remind its much larger neighbour of its independence.

By far the shortest route between the southern Senegalese region of Casamance and the capital, Dakar, goes through The Gambia but the border is currently closed, meaning the 420km (260-mile) journey journey is now twice as long. Travellers and lorries are driving all the way round The Gambia, via Tambacounda.

On the roads, which are often more pot hole than tarmac, this means that a five-six hour journey can - depending on the ferry crossing - take up to 15 hours.

The frontier is shut because of a two-month blockade by Senegalese drivers after the levy they have to pay to cross The Gambia was increased 100 times - from 4,000 CFA per truck to 400,000 CFA (£500; $700;.

Apart from revenue from tourism and peanuts, the country has little income and so is keen to preserve the money it earns from taxing travellers.

Hauliers' unions say no official explanation has been given and denounce a "unilateral decision", which, they say, violates the West Africa regional block Ecowas principle of free movement of people and goods within the region.

The Senegalese government has not been vocal about the issue, no doubt for fear of exacerbating relations with its neighbour.

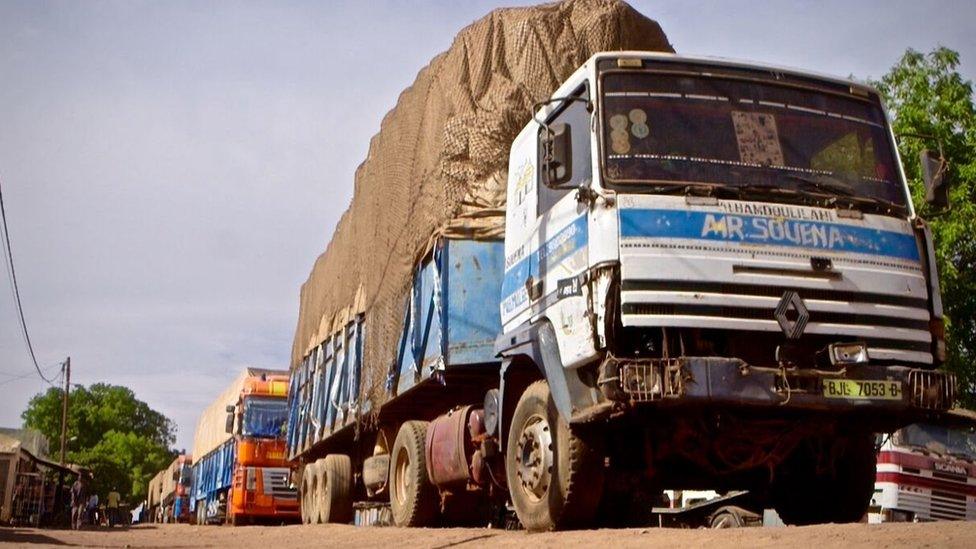

Among those hardest-hit by the border closure are those transporting goods into The Gambia and desperately waiting for it to reopen.

One driver who has been waiting on the border crossing for two months, says they cannot wait for the border to be reopened.

"We are tired of this," Khadim Lo says. "We are desperate. They must help us [by building a bridge or] allow free movement between the two countries. We don't have any coins in our pockets."

Another man says he has been waiting to take material to his building site in Gambia for more than a month.

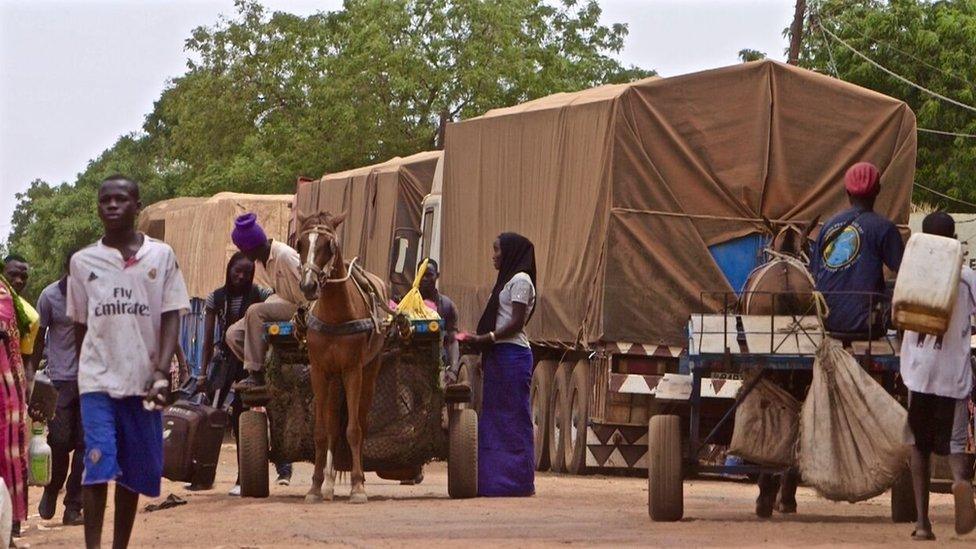

The closure has affected many travellers

Senegal's Foreign Affairs Minister, Mankeur Ndiaye, said they were waiting for Gambian officials to propose a meeting date after one due early this month in Dakar was postponed.

An Ecowas delegation has visited The Gambia and Senegal but did not speak publicly on the issue. It promised to release the results of its consultation soon.

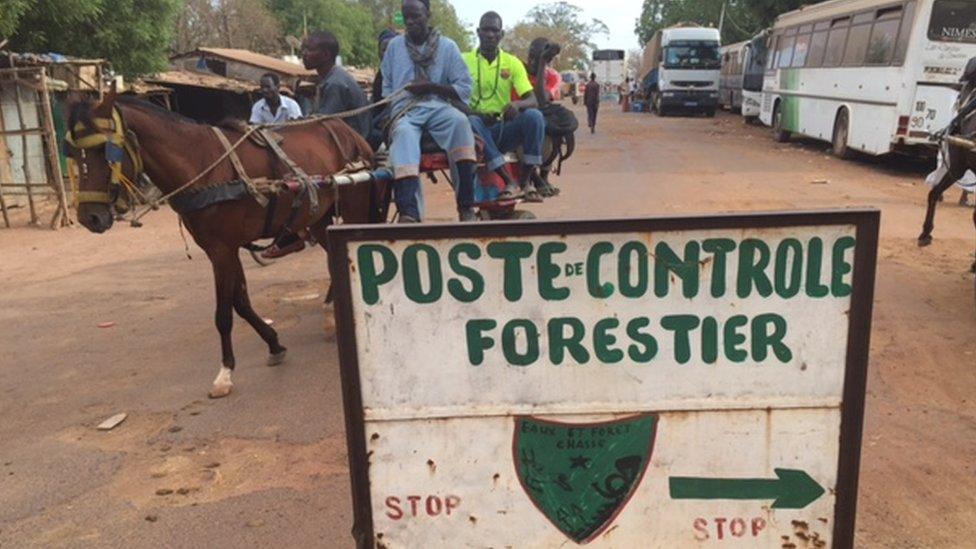

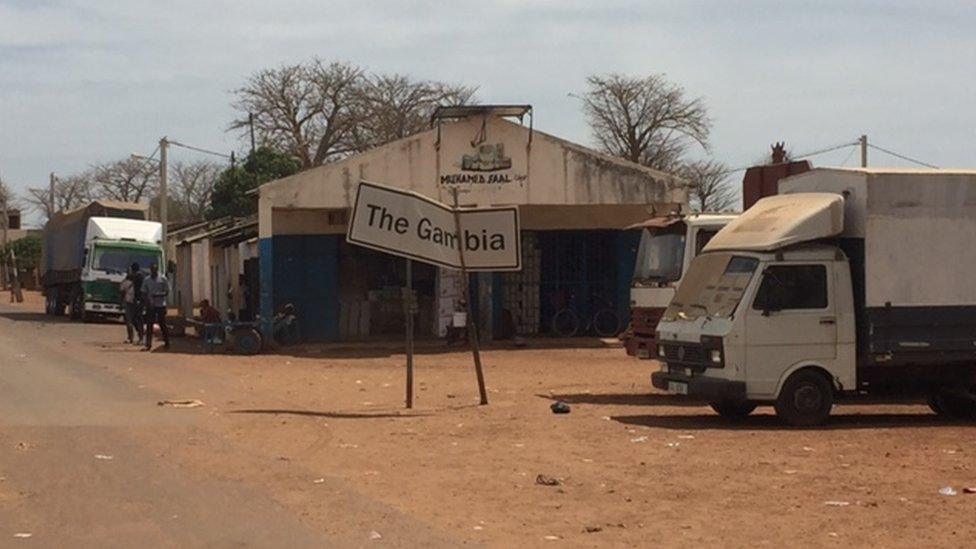

The normally hectic town of Keur Ayib on the Senegal-Gambia border is far quieter than usual because most traffic is going via Tambacounda.

There is a line of trucks parked on one side of the road, just a few metres from the border, waiting to cross into The Gambia, but they are not allowed to.

Travellers are free to cross the border on motorbikes and donkeys and then take mini-buses on the other side to continue their journey.

Rather than taking the long way round, some people have decided to split their journey into three stages - take one bus from Dakar to the border, another to cross The Gambia and then another from the border to Ziguinchor.

Vegetable shortage

Some people use horses and donkeys to cross the border

Each stage involves haggling for the fare, loading up the luggage and waiting for a new bus to fill up before it starts its journey, so most people prefer to travel via Tambacounda despite the extra distance.

While passengers are frustrated about the closure of the border, the bus drivers are happy to profit.

"The ticket price has increased and we are happy because we make more money," said one of the bus drivers.

Local people have also been benefiting from the closure, with young ladies selling water, snacks and other drinks to stranded passengers and truck drivers at the bus station.

The closure of the border has caused price increases and a shortage of cooking gas and other basic commodities in Gambia, a journalist told there told the BBC.

Some people are now using firewood and charcoal to cook, Aisha Dabo says.

There is little business going on in the main market of The Gambia's capital, Banjul, as the border closure means there are less vegetables and other fresh produce which are mainly imported from across the border in Senegal, she added.

Senegal and The Gambia have long been involved in a border disputes

Similar disputes and the occasional border closure have broken out several times in recent years but this is one of the longest.

The journey between Ziguinchor and Dakar via The Gambia also illustrates another major problem still holding back many African countries - a lack of infrastructure.

It was earlier last year that the foundation stone was laid for a long-mooted bridge across the River Gambia in order to significantly reduce journey times.

But since then, things have not moved even though Senegalese authorities have said that the funding of the 942-metre bridge had been secured through the African Development Bank.

It should cost 53bn CFA (£63m; $90m) and construction should last 36 months.

But many in Senegal suspect Gambia's President Yahya Jammeh does not really want the bridge, as it would remove his main source of leverage over his much larger neighbour.

Even when the border is open, travellers and lorries full of produce often have to wait for hours on end to board one of just two ferries which cross the river.

With a bridge and a good road, it should be possible to travel from Dakar to Ziguinchor in about five hours, rather than a full day, or sometimes even longer.

Some truck drivers say they can't wait for the border to be reopened

But with the seeming impasse on the bridge, another option has been mooted - building a bypass around The Gambia, which would not go as far as Tambacounda and would also avoid towns and villages on the way in order to speed up journey times.

Another option is the Atlantic Ocean.

Senegal's government has introduced two new boats sailing between Dakar and Ziguinchor.

But ever since the 2002 sinking of the Joola on that route - Africa's worst maritime disaster, which left at least 1,800 people dead - many in Casamance have been wary of sea travel.

This latest border row has also highlighted the isolation of Casamance, seen as one of the main factors behind the rebellion that has rumbled on in Senegal's most fertile region since 1981.

If Senegal's government wants to end that conflict, it needs to find a way to improve trade and transport links between Casamance and Dakar.

- Published14 May 2018

- Published12 April 2023