Can Barrow stem flow of young Gambians heading for Europe?

- Published

The Gambia is one of the poorest countries in the world

Considering its population of less than two million, The Gambia accounts for a high proportion of those crossing the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe. The BBC's Alastair Leithead asks whether the new president can change this.

In a tiny shop unit along a dark corridor and through a narrow alleyway in The Gambia's biggest market, Samba Ceesay is sorting through the clothes he has for sale.

He arrived back last November - just before the election - after 15 months away from home following what everyone here calls "the back way".

It's the well-trodden migrant path to Europe through Senegal, Mali and Burkina Faso to Niger, and then north through Libya to the coast, to risk a Mediterranean crossing.

Mr Ceesay, 26, got as far as Burkina Faso before he was captured by an organised crime syndicate.

"They said they would help me but they took everything I had - all my money and my things - and locked me up," he said.

"They threatened to kill me unless my family sent ransom money, but we have nothing. They held me for a month."

Eventually they released him, and despite having lost all his money he kept going.

Samba Ceesay had a terrible experience trying to reach Europe

He reached southern Libya, but with no job or chance of making the money needed to cross the Sahara or pay for passage across the Mediterranean, he gave up.

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) office in the migrant hub of Agadez in Niger, helped him return home to The Gambia.

Mr Ceesay's family were initially disappointed he hadn't made it - they'd supported his plan to head to Europe and try to earn money to send home.

Now Famara Njie from the IOM is helping him re-integrate through training to help improve his chances of getting a job.

"If you don't make your way to Europe and you come back empty-handed without any means to re-start your life, it makes things very, very difficult to re-integrate yourself back in the community," he said.

It's known as "irregular migration" - most people leaving The Gambia are economic migrants, and for the size of the country there are a lot of them.

There are less than two million Gambians, and by percentage of population more people head to Europe than any other nation.

"It is a growing problem, because we've seen people from all walks of life - policemen leaving their jobs, teachers leaving their jobs embarking on this way," said Mr Njie.

"Minors - those who should be in school to complete their basic education… we have seen them embarking on this journey, which is a really, really very troubling situation for the country."

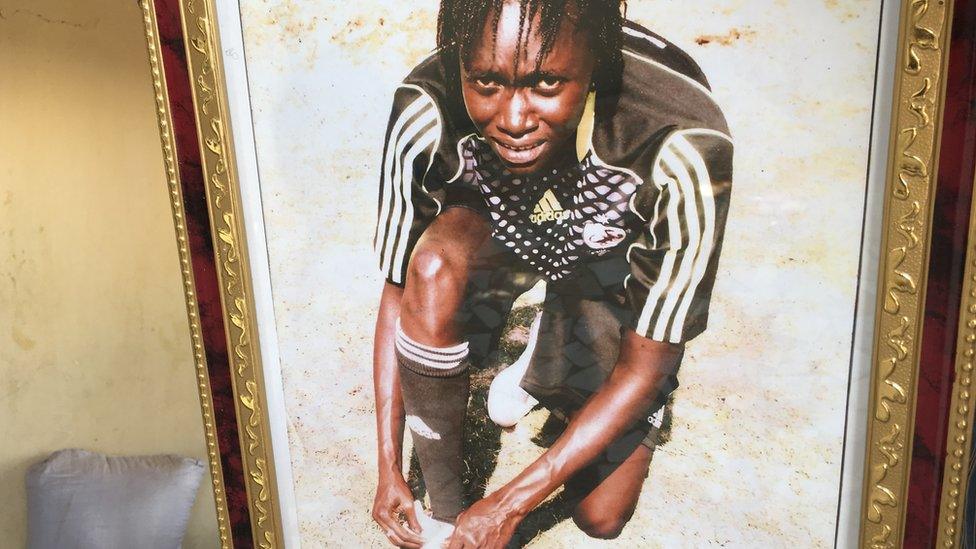

Top women's football side, Red Scorpions, lost their goalkeeper, who drowned in the Mediterranean last year

Across The Gambia thousands of people are leaving their homes.

Less than an hour's drive from the capital, in the village of Kitty, many people have left using "the back way".

People here are poor and it's strikingly clear whose relatives have made it to Europe, because they are building fantastic new homes.

Money goes a long way here and so remittances are paying for gleaming tin roofs, houses with fancy pillars and large courtyards.

There are satellite TV dishes attached to the walls and plots of land cleared and pegged out waiting for construction to begin.

It's this obvious incentive which drives many people to risk everything.

Migrants arriving in Italy and Greece (2016)

In a dusty clearing in central Banjul, amid the beautiful, orange, late afternoon light, the Red Scorpions are training.

They're the country's top women's football team and many also play for the national side.

Their goalkeeper, Fatim Jawara, 20, went missing last year, and then word came that she and her friend had drowned trying to cross the Mediterranean.

"She was so friendly, humble, always laughing - we were like twins," said her brother Momodou Jawara, 36, sitting with a photograph of her wearing her football strip.

"Thousands and thousands of people have gone - I wish I knew why.

"I don't have that kind of mentality, but what we believe is people always talk about greener pastures, wanting to be out doing something for their family as most of them complain about a lack of jobs."

He thinks she might have gone to try and play football in Europe "but I'm not in her mind, and I'm not sure what put her in it".

Fatim Jawara: She was so friendly, humble, always laughing, says her brother

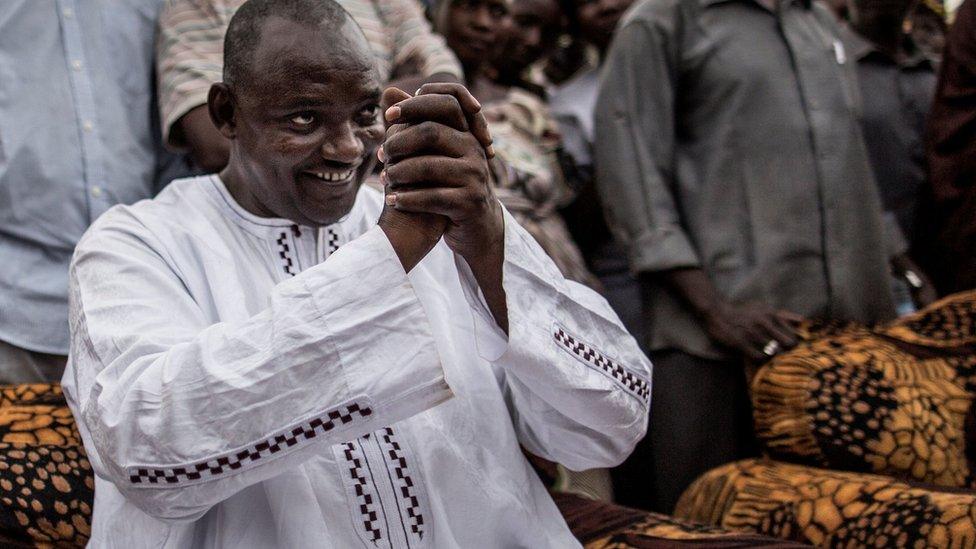

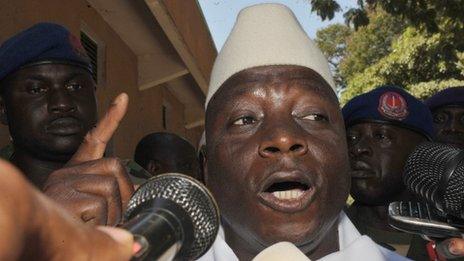

With the return of new President Adama Barrow, there are great expectations that life will improve after 22 years of Yahya Jammeh's rule.

Under Mr Jammeh, human rights and freedom of speech were not respected. While this might change with a new government, it will be more difficult to raise living standards in what is one of the poorest countries in the world.

"It will take time. What kind of factories are we going to build, what kind of industry are we going to provide for the youths?" asks Mr Jawara.

A huge deposit of oil was recently found off the coast of neighbouring Senegal.

It's believed that find may extend into Gambian territorial waters, which could provide a huge boost to the economy over the coming decades.

The new president will serve just three years and is barred from standing in the next election, so it's hoped he can focus on laying foundations for the economy to improve.

Big new houses built in poor villages show what reaching Europe means

But people have high expectations, which will be hindered by the complexities of coalition politics.

Seven different political parties joined forces, plucking Mr Barrow from relative obscurity to drive President Jammeh from power.

The Red Scorpions have high hopes.

"This new government coming in will help the youths to have more job opportunities, schools will be available for them. I can see a bright future for the Gambian youth," said striker Adama Tamba, 18.

"This new government, it will help us a lot," agreed Fatou Fatty, 19, the captain of the national team.

But there's a lot of work to do to prevent people being lured to take "the back way" to bring money home and lift their families out of poverty.

- Published23 January 2017

- Published19 January 2017

- Published22 January 2017

- Published13 December 2016

- Published12 April 2023